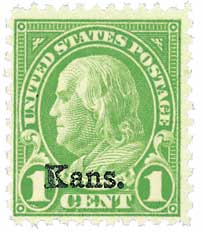

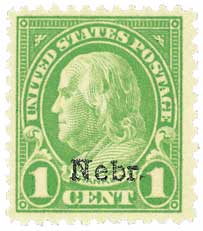

# 658 PB - 1929 1c Franklin, green, Kansas-Nebraska overprints

1929 Kansas-Nebraska Overprints

1¢ Kansas

First City: Newton, KS

Quantity Issued: 13,390,000

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 11 x 10.5

Color: Green

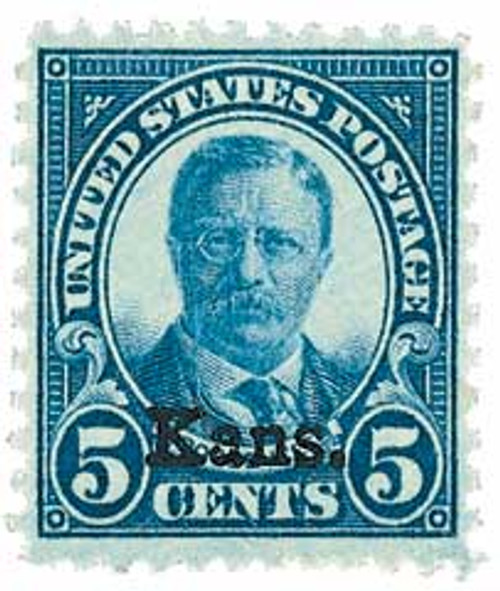

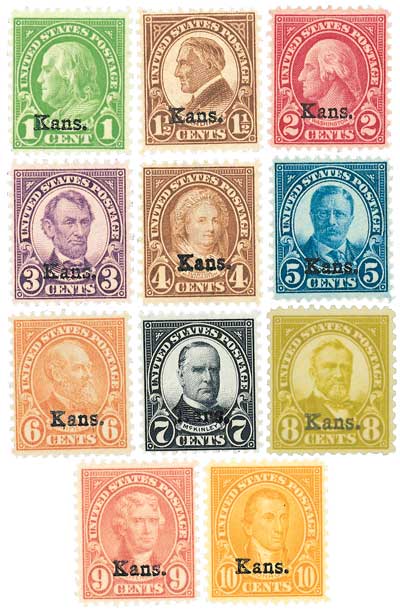

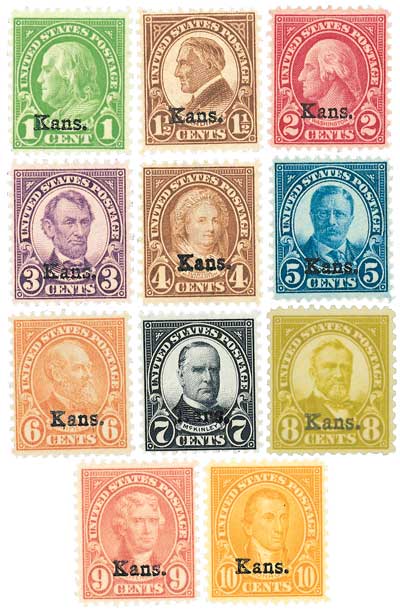

Kansas-Nebraska Stamps

During the 1920s, a rash of post office robberies baffled US postal inspectors. Burglars were stealing stamps in one state and then selling them in another. As the Post Office Department searched for a solution to put an end to the problem, the robberies became more frequent and more widespread, especially in the Midwest.

In February 1929, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing was authorized to apply special state overprints to the 1¢ through 10¢ denominations of the current regular issues, in an effort to put an end to the interstate sale of stolen postage stamps. Once the stamp had been produced, the name of the state where the stamps were to be used would be imprinted over the design. Such a move had been under consideration for some time, but the newly invented rotary press now made the idea feasible and affordable. It was hoped that the overprints would make it difficult to sell or use stamps from another state.

Kansas and Nebraska were selected as trial states since the postal inspector who had made the suggestion was in charge of inspections in these two states and would be supervising the experiment. They were also among the states that suffered – in one year alone, machine-gun toting gangsters had stolen more than $200,000 (over $10 million today) worth of stamps. The new overprints were abbreviations of the states (Kans. and Nebr.) and were applied in the same manner as precancels. Each state received a small supply of stamps for each of its post offices.

If successful, it was decided that these overprints would be used in the other 46 states as well (Alaska and Hawaii didn’t become states until 1959). Fortunately for collectors, problems arose and the idea was abandoned – otherwise there could have been 48 different varieties of each stamp issued, which would have been a nightmare for philatelists.

The Kansas-Nebraska stamps were officially placed on sale on May 1, 1929 (though some stamps were released on April 15). When they were released, the Post Office Department made the announcement that these stamps were valid as postage throughout the United States. However, these overprints were very similar to the current precancels, which were not valid for use outside the intended area. Numerous complaints were received because post offices in other states were not accepting the overprinted stamps as evidence of pre-payment.

Others argued that the program was a farce intended to save money. They pointed out that small post offices were required to purchase an entire year’s supply of stamps at once under the plan, which cut government distribution costs by more than half. Those critics claimed that the overprints were a method to discourage would-be thieves from stealing the huge stockpiles of stamps that would be stored in poorly defended small towns as a result of the cost-cutting program. In the wake of such widespread criticism, officials halted the experiment in less than a year and let the existing supply of stamps exhaust itself. Consequently, not many of these stamps were produced. For example, there were just 530,000 9¢ Nebraska stamps issued, which meant there was less than one 9¢ stamp for every two people in the state, whose population was about 1.3 million.

As early as June 1929, collectors were eagerly seeking these new and scarce stamps. Various types surfaced, including the shifted overprints, which resulted in strips containing one stamp completely lacking the overprint. Because there were so few stamps and such a great demand for them, these issues became a prime target for counterfeiters. The most common forgeries were known as the “California Fakes,” since they were first discovered in San Francisco. Since the genuine overprints were printed using electrotype plates and the forgeries were done using a typewriter, the difference between the two is easy to distinguish. On a genuine overprint, the image was printed on the surface rather than impressed into the stamp. Thus, the ink lies flat on the surface and almost appears raised. Most importantly, if one turns the stamp over, the image doesn’t appear impressed, and it never breaks the gum.

1929 Kansas-Nebraska Overprints

1¢ Kansas

First City: Newton, KS

Quantity Issued: 13,390,000

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 11 x 10.5

Color: Green

Kansas-Nebraska Stamps

During the 1920s, a rash of post office robberies baffled US postal inspectors. Burglars were stealing stamps in one state and then selling them in another. As the Post Office Department searched for a solution to put an end to the problem, the robberies became more frequent and more widespread, especially in the Midwest.

In February 1929, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing was authorized to apply special state overprints to the 1¢ through 10¢ denominations of the current regular issues, in an effort to put an end to the interstate sale of stolen postage stamps. Once the stamp had been produced, the name of the state where the stamps were to be used would be imprinted over the design. Such a move had been under consideration for some time, but the newly invented rotary press now made the idea feasible and affordable. It was hoped that the overprints would make it difficult to sell or use stamps from another state.

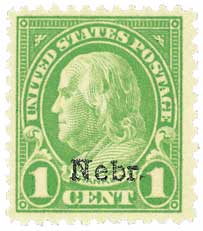

Kansas and Nebraska were selected as trial states since the postal inspector who had made the suggestion was in charge of inspections in these two states and would be supervising the experiment. They were also among the states that suffered – in one year alone, machine-gun toting gangsters had stolen more than $200,000 (over $10 million today) worth of stamps. The new overprints were abbreviations of the states (Kans. and Nebr.) and were applied in the same manner as precancels. Each state received a small supply of stamps for each of its post offices.

If successful, it was decided that these overprints would be used in the other 46 states as well (Alaska and Hawaii didn’t become states until 1959). Fortunately for collectors, problems arose and the idea was abandoned – otherwise there could have been 48 different varieties of each stamp issued, which would have been a nightmare for philatelists.

The Kansas-Nebraska stamps were officially placed on sale on May 1, 1929 (though some stamps were released on April 15). When they were released, the Post Office Department made the announcement that these stamps were valid as postage throughout the United States. However, these overprints were very similar to the current precancels, which were not valid for use outside the intended area. Numerous complaints were received because post offices in other states were not accepting the overprinted stamps as evidence of pre-payment.

Others argued that the program was a farce intended to save money. They pointed out that small post offices were required to purchase an entire year’s supply of stamps at once under the plan, which cut government distribution costs by more than half. Those critics claimed that the overprints were a method to discourage would-be thieves from stealing the huge stockpiles of stamps that would be stored in poorly defended small towns as a result of the cost-cutting program. In the wake of such widespread criticism, officials halted the experiment in less than a year and let the existing supply of stamps exhaust itself. Consequently, not many of these stamps were produced. For example, there were just 530,000 9¢ Nebraska stamps issued, which meant there was less than one 9¢ stamp for every two people in the state, whose population was about 1.3 million.

As early as June 1929, collectors were eagerly seeking these new and scarce stamps. Various types surfaced, including the shifted overprints, which resulted in strips containing one stamp completely lacking the overprint. Because there were so few stamps and such a great demand for them, these issues became a prime target for counterfeiters. The most common forgeries were known as the “California Fakes,” since they were first discovered in San Francisco. Since the genuine overprints were printed using electrotype plates and the forgeries were done using a typewriter, the difference between the two is easy to distinguish. On a genuine overprint, the image was printed on the surface rather than impressed into the stamp. Thus, the ink lies flat on the surface and almost appears raised. Most importantly, if one turns the stamp over, the image doesn’t appear impressed, and it never breaks the gum.