# 589 - 1926 8c Grant, olive green

U.S. #589

Series of 1923-26 8¢ Ulysses S. Grant

First City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity Issued: 165,921,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 10

Color: Olive green

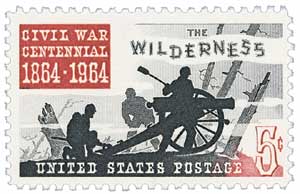

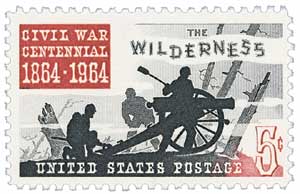

Battle Of Spotsylvania Court House

On May 7, the Union Army realized they could not win the Battle of the Wilderness, so Ulysses S. Grant turned his forces southeast to the crossroads at Spotsylvania Court House, hoping to get between the Confederate Army and Richmond.

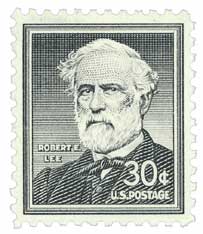

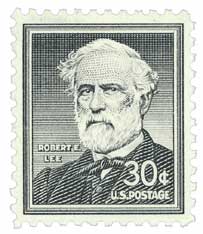

Meanwhile, Robert E. Lee ordered Major General William T. Anderson to travel on a path parallel to the Union’s route to protect the roadway. Anderson initially considered having his men rest the night in the Wilderness, but the burning forests and smell of wounded and dead men were unbearable so they began their march that night. As a result, they arrived at Spotsylvania ahead of the Union Army, which helped keep the crossroads in Confederate hands.

Major Generals Gouverneur Warren and John Sedgwick led the Union advance to Spotsylvania. On May 8, they encountered the Confederates at Laurel Hill to the northwest of their target. Thinking they were smaller cavalry divisions, Warren ordered an immediate attack. They were met by Anderson’s corps, which repulsed the charge. Both sides then began building earthworks. That evening, the Union soldiers attempted another strike, but they were once again sent back to their defenses.

The Confederate and Union forces worked through the night to extend their fortifications. As the sun rose on May 9, the Union Army noticed a section of the Confederate defenses that jutted out more than a mile from the rest of the line. Soldiers called it the “Mule Shoe” because of its shape, but commanders on both sides realized it would be hard to defend.

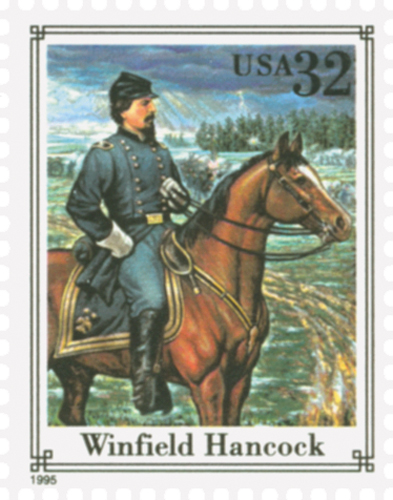

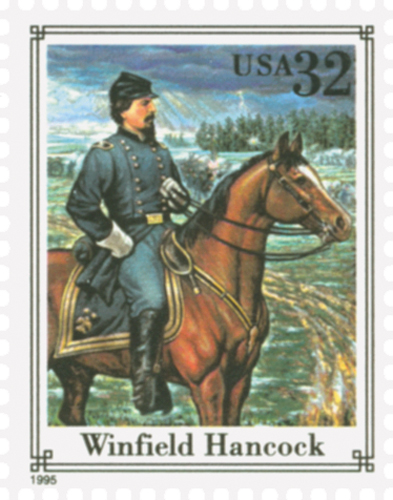

Early in the evening on May 10, a young Union colonel, Emory Upton, led about 5,000 men through the woods surrounding the Mule Shoe. They attacked at a weak point and easily broke through Confederate barriers and seized some heavy artillery. The Southern Army recovered quickly, and Upton did not have the reinforcements necessary to sustain the assault, so they retreated. Though the plan was not successful, Grant believed it would work with a larger force. He assigned Major General Winfield Hancock’s II Corps to the task of striking the Mule Shoe.

At 4:30 a.m. on May 12, 20,000 Union soldiers were ordered to charge the Mule Shoe. Immediately, the North overcame the Confederate works. Once inside, their progress stopped as thousands of soldiers tried to squeeze through the narrow opening, breaking formation. The Rebels capitalized on the confusion, racing to fill the gap. Grant sent reinforcements to the western section of the fighting. This portion became the site of heavy hand-to-hand combat and was later known as the “Bloody Angle.”

Fighting continued throughout the day and into the night on all sides of the Mule Shoe. The Confederates constructed a new defensive line 500 yards behind the area. By 4 a.m. the earthworks were ready and the Rebels withdrew. As the sun rose, the devastation that resulted from the previous day was evident. Trees had been severed from rifle fire and wounded men lay all around. One Southern soldier wrote, “The battle of Thursday was one of the bloodiest that ever dyed God’s footstool with human gore.”

While the battle raged at Mule Shoe, Warren attacked at Laurel Hill again. His men had attempted to best the enemy four times before and were not enthusiastic about going against the Confederates’ stronghold again. No ground was gained, and the casualty rate was high for the Union troops. Warren was relieved of his command and his men withdrew from the area.

Grant moved his army to the east of Spotsylvania. Though there were small skirmishes in the days that followed, heavy rain and muddy roads kept the Union from staging a coordinated attack. By May 20, both sides were moving on, but they would meet again. Grant did not attain the quick victory over Lee he had hoped for. The two armies would continue to engage in battles throughout the coming year. The causalities were high on both sides (totaling 32,000), but the Confederate Army did not have the men to replace their losses, especially officers. The lack of reinforcements would contribute significantly to the outcome of the Civil War.

Click here for more Civil War stamps.

U.S. #589

Series of 1923-26 8¢ Ulysses S. Grant

First City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity Issued: 165,921,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 10

Color: Olive green

Battle Of Spotsylvania Court House

On May 7, the Union Army realized they could not win the Battle of the Wilderness, so Ulysses S. Grant turned his forces southeast to the crossroads at Spotsylvania Court House, hoping to get between the Confederate Army and Richmond.

Meanwhile, Robert E. Lee ordered Major General William T. Anderson to travel on a path parallel to the Union’s route to protect the roadway. Anderson initially considered having his men rest the night in the Wilderness, but the burning forests and smell of wounded and dead men were unbearable so they began their march that night. As a result, they arrived at Spotsylvania ahead of the Union Army, which helped keep the crossroads in Confederate hands.

Major Generals Gouverneur Warren and John Sedgwick led the Union advance to Spotsylvania. On May 8, they encountered the Confederates at Laurel Hill to the northwest of their target. Thinking they were smaller cavalry divisions, Warren ordered an immediate attack. They were met by Anderson’s corps, which repulsed the charge. Both sides then began building earthworks. That evening, the Union soldiers attempted another strike, but they were once again sent back to their defenses.

The Confederate and Union forces worked through the night to extend their fortifications. As the sun rose on May 9, the Union Army noticed a section of the Confederate defenses that jutted out more than a mile from the rest of the line. Soldiers called it the “Mule Shoe” because of its shape, but commanders on both sides realized it would be hard to defend.

Early in the evening on May 10, a young Union colonel, Emory Upton, led about 5,000 men through the woods surrounding the Mule Shoe. They attacked at a weak point and easily broke through Confederate barriers and seized some heavy artillery. The Southern Army recovered quickly, and Upton did not have the reinforcements necessary to sustain the assault, so they retreated. Though the plan was not successful, Grant believed it would work with a larger force. He assigned Major General Winfield Hancock’s II Corps to the task of striking the Mule Shoe.

At 4:30 a.m. on May 12, 20,000 Union soldiers were ordered to charge the Mule Shoe. Immediately, the North overcame the Confederate works. Once inside, their progress stopped as thousands of soldiers tried to squeeze through the narrow opening, breaking formation. The Rebels capitalized on the confusion, racing to fill the gap. Grant sent reinforcements to the western section of the fighting. This portion became the site of heavy hand-to-hand combat and was later known as the “Bloody Angle.”

Fighting continued throughout the day and into the night on all sides of the Mule Shoe. The Confederates constructed a new defensive line 500 yards behind the area. By 4 a.m. the earthworks were ready and the Rebels withdrew. As the sun rose, the devastation that resulted from the previous day was evident. Trees had been severed from rifle fire and wounded men lay all around. One Southern soldier wrote, “The battle of Thursday was one of the bloodiest that ever dyed God’s footstool with human gore.”

While the battle raged at Mule Shoe, Warren attacked at Laurel Hill again. His men had attempted to best the enemy four times before and were not enthusiastic about going against the Confederates’ stronghold again. No ground was gained, and the casualty rate was high for the Union troops. Warren was relieved of his command and his men withdrew from the area.

Grant moved his army to the east of Spotsylvania. Though there were small skirmishes in the days that followed, heavy rain and muddy roads kept the Union from staging a coordinated attack. By May 20, both sides were moving on, but they would meet again. Grant did not attain the quick victory over Lee he had hoped for. The two armies would continue to engage in battles throughout the coming year. The causalities were high on both sides (totaling 32,000), but the Confederate Army did not have the men to replace their losses, especially officers. The lack of reinforcements would contribute significantly to the outcome of the Civil War.

Click here for more Civil War stamps.