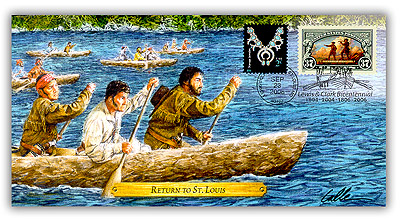

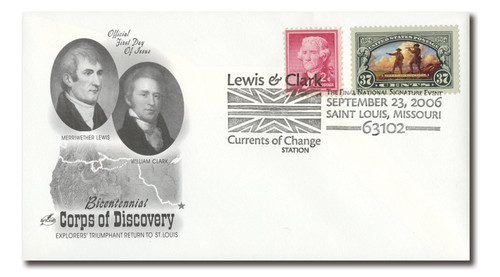

# 571475 - 2006 Lewis & Clark "Triumphant Return to St. Louis" Commemorative Cover

Lewis And Clark’s Corps Of Discovery

On May 21, 1804, Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery departed St. Charles on the Missouri River to begin their exploration of the American West.

In 1803, Robert Livingston and James Monroe struck “the greatest real estate deal in history” – the Louisiana Purchase. As representatives for President Thomas Jefferson, they purchased a 530-million-acre area for $15 million, or about 3¢ per acre.

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase sparked interest in westward expansion. However, little was known about the territory. Shortly after the purchase, President Jefferson convinced Congress to appropriate $2,500 to fund an expedition led by Captain Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. The purpose of the expedition was to find a direct and predictable waterway across the continent for commerce. In addition, the group was to study Indian tribes, botany, and geology in the territory.

By many accounts, the expedition began on May 14, 1804. On that day, Clark and a group of men in three boats departed Camp River Dubois, Illinois. They traveled to St. Charles, where they would wait several days for Captain Lewis, who had business to attend to in St. Louis. Then on May 20, Lewis rode over land to St. Charles to meet up with Clark and the rest of the Corps. They would begin their journey together the next day.

The Corps of Discovery, led by Lewis and Clark, officially set out about 3:30 p.m. on May 21, 1804. The men on the boats, as well as those watching from the shore, cheered as the expedition left for its long journey. Officially, Lewis and Clark were assigned to find a path to the Pacific Ocean, preferably by water, in order to build trade. But for Jefferson, who was very interested in all natural sciences, it promised to be a treasure trove of knowledge, as well.

By late 1804, the expedition reached Fort Mandan in central North Dakota, where they set up their winter camp. While there, Lewis and Clark sent a shipment to Jefferson of some of their findings. Four boxes, two trunks, and three cages were shipped to Washington, D.C. They included Native American items, as well as animal skins, bones, and antlers. They also sent a live prairie dog, four magpies, and a grouse. In addition, Jefferson received plant, soil, and mineral samples.

A delighted Jefferson cataloged the contents and then shipped them to at least three different locations, including Monticello, the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, and the Peale Museum in Baltimore. In all, 108 plant and animal specimens, 68 mineral samples, and William Clark’s map were received.

Meanwhile, out west, a young Shoshone woman named Sacajawea joined the group and guided them westward in the spring. Sacajawea served as a translator during the journey. In addition to her interpretations, the sight of a woman with an infant helped divert hostile actions by other Indian tribes.

Then in December of 1805, Lewis and Clark traveled down the Columbia River to reach the Pacific Ocean. Clark wrote in his journal, “Ocean in view! O! The Joy!” They then spent the winter camped in Oregon before beginning their journey home. The expedition returned to St. Louis on September 23, 1806. Over the course of 28 months, they traveled 8,000 miles. In spite of the grueling journey through unknown territory, the only expedition death resulted from appendicitis.

The Lewis and Clark expedition discovered vital information about America’s new territory and the native tribes who inhabited the land. Lewis and Clark described 178 plants and 122 species of animals as they traveled along the Missouri, across the Continental Divide, and to the Pacific Ocean. Carefully documented information gathered by the group members resulted in the first accurate mapping of the United States west of the Mississippi River.

Click here for more stamps and covers honoring the expedition.

Click here to read daily journal entries from Lewis, Clark, and others involved in the expedition.

Lewis And Clark’s Corps Of Discovery

On May 21, 1804, Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery departed St. Charles on the Missouri River to begin their exploration of the American West.

In 1803, Robert Livingston and James Monroe struck “the greatest real estate deal in history” – the Louisiana Purchase. As representatives for President Thomas Jefferson, they purchased a 530-million-acre area for $15 million, or about 3¢ per acre.

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase sparked interest in westward expansion. However, little was known about the territory. Shortly after the purchase, President Jefferson convinced Congress to appropriate $2,500 to fund an expedition led by Captain Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. The purpose of the expedition was to find a direct and predictable waterway across the continent for commerce. In addition, the group was to study Indian tribes, botany, and geology in the territory.

By many accounts, the expedition began on May 14, 1804. On that day, Clark and a group of men in three boats departed Camp River Dubois, Illinois. They traveled to St. Charles, where they would wait several days for Captain Lewis, who had business to attend to in St. Louis. Then on May 20, Lewis rode over land to St. Charles to meet up with Clark and the rest of the Corps. They would begin their journey together the next day.

The Corps of Discovery, led by Lewis and Clark, officially set out about 3:30 p.m. on May 21, 1804. The men on the boats, as well as those watching from the shore, cheered as the expedition left for its long journey. Officially, Lewis and Clark were assigned to find a path to the Pacific Ocean, preferably by water, in order to build trade. But for Jefferson, who was very interested in all natural sciences, it promised to be a treasure trove of knowledge, as well.

By late 1804, the expedition reached Fort Mandan in central North Dakota, where they set up their winter camp. While there, Lewis and Clark sent a shipment to Jefferson of some of their findings. Four boxes, two trunks, and three cages were shipped to Washington, D.C. They included Native American items, as well as animal skins, bones, and antlers. They also sent a live prairie dog, four magpies, and a grouse. In addition, Jefferson received plant, soil, and mineral samples.

A delighted Jefferson cataloged the contents and then shipped them to at least three different locations, including Monticello, the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, and the Peale Museum in Baltimore. In all, 108 plant and animal specimens, 68 mineral samples, and William Clark’s map were received.

Meanwhile, out west, a young Shoshone woman named Sacajawea joined the group and guided them westward in the spring. Sacajawea served as a translator during the journey. In addition to her interpretations, the sight of a woman with an infant helped divert hostile actions by other Indian tribes.

Then in December of 1805, Lewis and Clark traveled down the Columbia River to reach the Pacific Ocean. Clark wrote in his journal, “Ocean in view! O! The Joy!” They then spent the winter camped in Oregon before beginning their journey home. The expedition returned to St. Louis on September 23, 1806. Over the course of 28 months, they traveled 8,000 miles. In spite of the grueling journey through unknown territory, the only expedition death resulted from appendicitis.

The Lewis and Clark expedition discovered vital information about America’s new territory and the native tribes who inhabited the land. Lewis and Clark described 178 plants and 122 species of animals as they traveled along the Missouri, across the Continental Divide, and to the Pacific Ocean. Carefully documented information gathered by the group members resulted in the first accurate mapping of the United States west of the Mississippi River.

Click here for more stamps and covers honoring the expedition.

Click here to read daily journal entries from Lewis, Clark, and others involved in the expedition.