# 560 PB - 1923 8c Grant, olive green

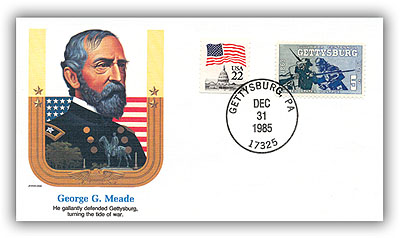

U.S. #560

Series of 1922-25

8¢ Ulysses S. Grant

Issue Date: May 1, 1923

First City: Washington, D.C.

Issue Quantity: 367,196,477

Wheels of Progress

In 1847, when the printing presses first began to move, they didn’t roll – they “stamped” in a process known as flat plate printing. The Regular Series of 1922 was the last to be printed by flat plate press, after which stamps were produced by rotary press printing.

By 1926, all denominations up to 10¢ – except the new ½¢ – were printed by rotary press. For a while, $1 to $5 issues were done on flat plate press due to smaller demand.

The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant

18th American President

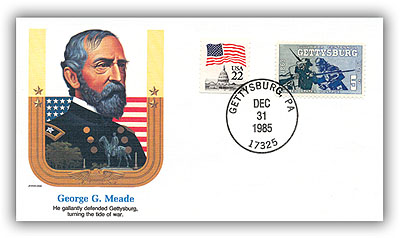

Following the Union victory on April 9, 1865, Grant became a national hero. He was so popular, in fact, he was elected President in 1868. Unfortunately, Grant’s lack of prior political experience caused him to fall prey to unscrupulous politicians. He appointed many of his friends to cabinet positions, and within months, his administration was fraught with scandal. One such scandal involved Grant’s own brother-in-law providing insider information to the financier Jay Gould, who was attempting to corner the gold market.

Despite the scandals of his first administration, Ulysses Grant was elected to a second term as President. This term proved more disastrous than the first. Several high-ranking government officials were involved in illegal stock dealings in connection with the Union Pacific Railroad. Two members of Grant’s own cabinet were forced to resign rather than face impeachment for their involvement in the Whiskey Ring, where the U.S. government was swindled out of millions of dollars in excise taxes.

Following his second term in office, Grant retired to New York. After the bank he had invested in went bankrupt, Grant raised money by writing his memoirs. He died on July 23, 1885, just a few weeks after completing his writing.

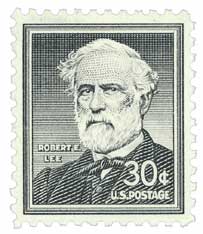

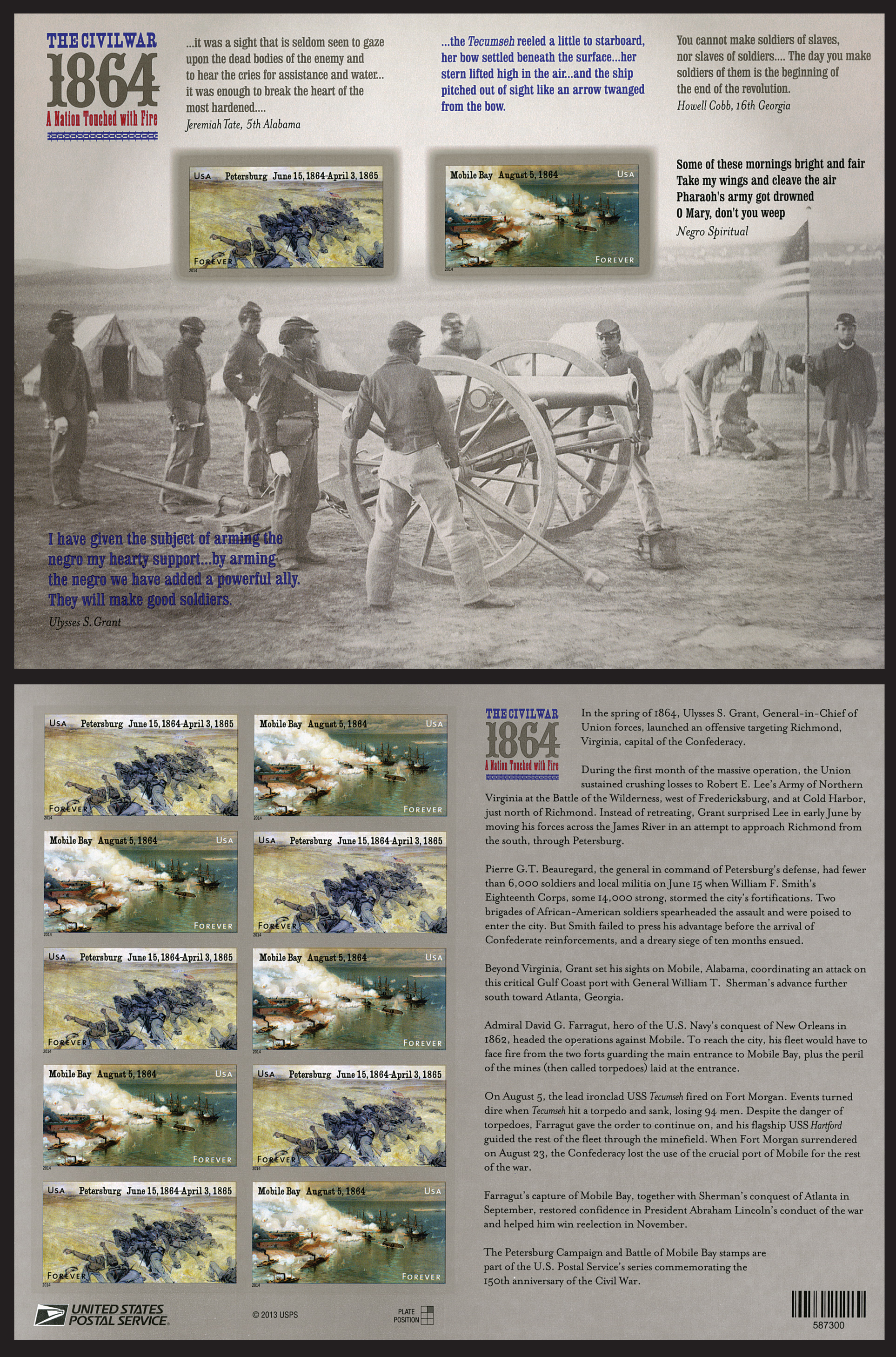

On July 30, 1864, Union forces launched the surprise Battle of the Crater. They dug tunnels under Confederate positions and set off explosives to catch them by surprise, but poor decisions led the battle to turn against them. The siege of Petersburg continued through the summer of 1864. Both sides reinforced their fortifications and dug more trenches. Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant had learned he could not defeat Lee’s men when they were in a defensive position. By June, Grant was open to suggestions, even if they seemed far-fetched. Union Major General Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps included the 48th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, made up mostly of former coal miners. Under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Pleasants, the division proposed digging a tunnel under Elliott’s Salient, the closest point in the Confederate fortifications. Once completed, they would explode the mine, taking the Southern Army by surprise. Burnside presented the plan to Major General Meade and Grant, who both approved it, considering the project a good way to keep the men busy during the siege. The digging began on June 25. Pleasants, a former mining engineer, supervised the round-the-clock shifts. Dirt was removed by the bucketful and on homemade sledges. Wood was taken from a mill and an old bridge to shore up the sides of the 500-foot tunnel. The crew even devised a ventilation system to send fresh air to the workers. Some Confederate soldiers claimed they heard digging beneath them, but General Lee refused to believe the rumors. Once the miners reached the desired length, they branched sideways for 75 feet, forming a T-shape. The tunnel was completed on July 23, and the last section was filled with 8,000 pounds of gunpowder and sealed off. While the volunteers from Pennsylvania were digging, other troops were preparing for the attack. General Burnside trained a division of United States Colored Troops, commanded by Brigadier General Edward Ferrero. They practiced using ladders to exit their trenches and enter the opening quickly. After entering the breach, the men would move along the sides of the crater to secure the area. The Union Army planned to use the devastation and confusion caused by the explosion to take Petersburg. The day before the attack, General Meade made a change of plans. He ordered Burnside to use white troops to lead the attack, instead of the US Colored Troops. Brigadier General James H. Ledlie’s 1st Division was chosen to enter first, but his men were not briefed on the plan. On July 30, the fuse was lit at 3:15 a.m. The miners had been given poor-quality fuses that had to be spliced together. After waiting an hour for the explosion, two volunteers entered the mine, respliced the fuse, relit it, and ran outside. At 4:45, the Confederates were awakened by an eruption of dirt and debris. A crater 170 feet long, 100 feet wide, and about 30 feet deep was created, and over 275 rebel troops were killed immediately. Ledlie’s men hesitated to leave their trenches and took additional time to climb out. When the Union soldiers reached the crater, they took cover in it rather than encircling it as the black soldiers had been trained to do. By that time, Confederate Major General William Mahone regrouped his men, who aimed their guns and artillery directly into the crowd. Rather than ordering a retreat, Burnside sent Ferrero and his troops into battle. Despite great losses, the Union was able to secure the right side of the crater, but a counterattack pushed them back to their trenches. The fighting subsided by early afternoon, and the Union missed an opportunity to end the siege at Petersburg. Ledlie was dismissed because of his poor leadership and reports he was drunk at the time of the battle. Burnside was also removed from command. Mining engineer Pleasants was praised for the concept and construction of the mine. He was later appointed a brevet brigadier general. Mahone’s quick actions and successful counterattack earned him a reputation as one of the Confederacy’s best generals in the final year of the Civil War. The large hole in the ground can still be seen today. It is a testimony to the ingenuity of Pennsylvania miners and tragic loss of life as a result of the Battle of the Crater.The Battle of the Crater

U.S. #560

Series of 1922-25

8¢ Ulysses S. Grant

Issue Date: May 1, 1923

First City: Washington, D.C.

Issue Quantity: 367,196,477

Wheels of Progress

In 1847, when the printing presses first began to move, they didn’t roll – they “stamped” in a process known as flat plate printing. The Regular Series of 1922 was the last to be printed by flat plate press, after which stamps were produced by rotary press printing.

By 1926, all denominations up to 10¢ – except the new ½¢ – were printed by rotary press. For a while, $1 to $5 issues were done on flat plate press due to smaller demand.

The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant

18th American President

Following the Union victory on April 9, 1865, Grant became a national hero. He was so popular, in fact, he was elected President in 1868. Unfortunately, Grant’s lack of prior political experience caused him to fall prey to unscrupulous politicians. He appointed many of his friends to cabinet positions, and within months, his administration was fraught with scandal. One such scandal involved Grant’s own brother-in-law providing insider information to the financier Jay Gould, who was attempting to corner the gold market.

Despite the scandals of his first administration, Ulysses Grant was elected to a second term as President. This term proved more disastrous than the first. Several high-ranking government officials were involved in illegal stock dealings in connection with the Union Pacific Railroad. Two members of Grant’s own cabinet were forced to resign rather than face impeachment for their involvement in the Whiskey Ring, where the U.S. government was swindled out of millions of dollars in excise taxes.

Following his second term in office, Grant retired to New York. After the bank he had invested in went bankrupt, Grant raised money by writing his memoirs. He died on July 23, 1885, just a few weeks after completing his writing.

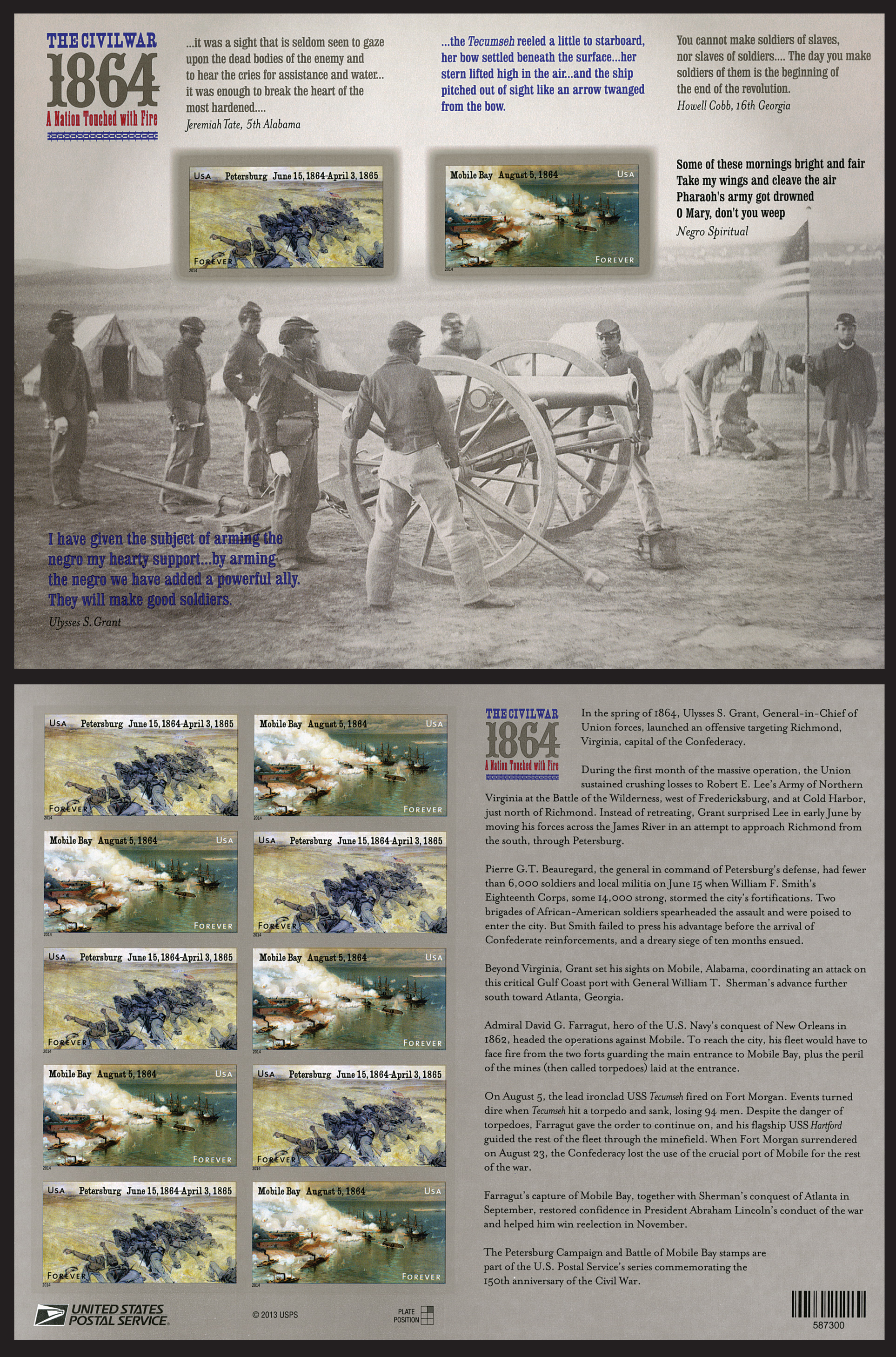

On July 30, 1864, Union forces launched the surprise Battle of the Crater. They dug tunnels under Confederate positions and set off explosives to catch them by surprise, but poor decisions led the battle to turn against them. The siege of Petersburg continued through the summer of 1864. Both sides reinforced their fortifications and dug more trenches. Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant had learned he could not defeat Lee’s men when they were in a defensive position. By June, Grant was open to suggestions, even if they seemed far-fetched. Union Major General Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps included the 48th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, made up mostly of former coal miners. Under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Pleasants, the division proposed digging a tunnel under Elliott’s Salient, the closest point in the Confederate fortifications. Once completed, they would explode the mine, taking the Southern Army by surprise. Burnside presented the plan to Major General Meade and Grant, who both approved it, considering the project a good way to keep the men busy during the siege. The digging began on June 25. Pleasants, a former mining engineer, supervised the round-the-clock shifts. Dirt was removed by the bucketful and on homemade sledges. Wood was taken from a mill and an old bridge to shore up the sides of the 500-foot tunnel. The crew even devised a ventilation system to send fresh air to the workers. Some Confederate soldiers claimed they heard digging beneath them, but General Lee refused to believe the rumors. Once the miners reached the desired length, they branched sideways for 75 feet, forming a T-shape. The tunnel was completed on July 23, and the last section was filled with 8,000 pounds of gunpowder and sealed off. While the volunteers from Pennsylvania were digging, other troops were preparing for the attack. General Burnside trained a division of United States Colored Troops, commanded by Brigadier General Edward Ferrero. They practiced using ladders to exit their trenches and enter the opening quickly. After entering the breach, the men would move along the sides of the crater to secure the area. The Union Army planned to use the devastation and confusion caused by the explosion to take Petersburg. The day before the attack, General Meade made a change of plans. He ordered Burnside to use white troops to lead the attack, instead of the US Colored Troops. Brigadier General James H. Ledlie’s 1st Division was chosen to enter first, but his men were not briefed on the plan. On July 30, the fuse was lit at 3:15 a.m. The miners had been given poor-quality fuses that had to be spliced together. After waiting an hour for the explosion, two volunteers entered the mine, respliced the fuse, relit it, and ran outside. At 4:45, the Confederates were awakened by an eruption of dirt and debris. A crater 170 feet long, 100 feet wide, and about 30 feet deep was created, and over 275 rebel troops were killed immediately. Ledlie’s men hesitated to leave their trenches and took additional time to climb out. When the Union soldiers reached the crater, they took cover in it rather than encircling it as the black soldiers had been trained to do. By that time, Confederate Major General William Mahone regrouped his men, who aimed their guns and artillery directly into the crowd. Rather than ordering a retreat, Burnside sent Ferrero and his troops into battle. Despite great losses, the Union was able to secure the right side of the crater, but a counterattack pushed them back to their trenches. The fighting subsided by early afternoon, and the Union missed an opportunity to end the siege at Petersburg. Ledlie was dismissed because of his poor leadership and reports he was drunk at the time of the battle. Burnside was also removed from command. Mining engineer Pleasants was praised for the concept and construction of the mine. He was later appointed a brevet brigadier general. Mahone’s quick actions and successful counterattack earned him a reputation as one of the Confederacy’s best generals in the final year of the Civil War. The large hole in the ground can still be seen today. It is a testimony to the ingenuity of Pennsylvania miners and tragic loss of life as a result of the Battle of the Crater.The Battle of the Crater