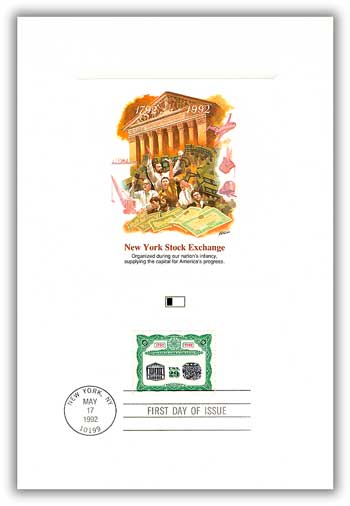

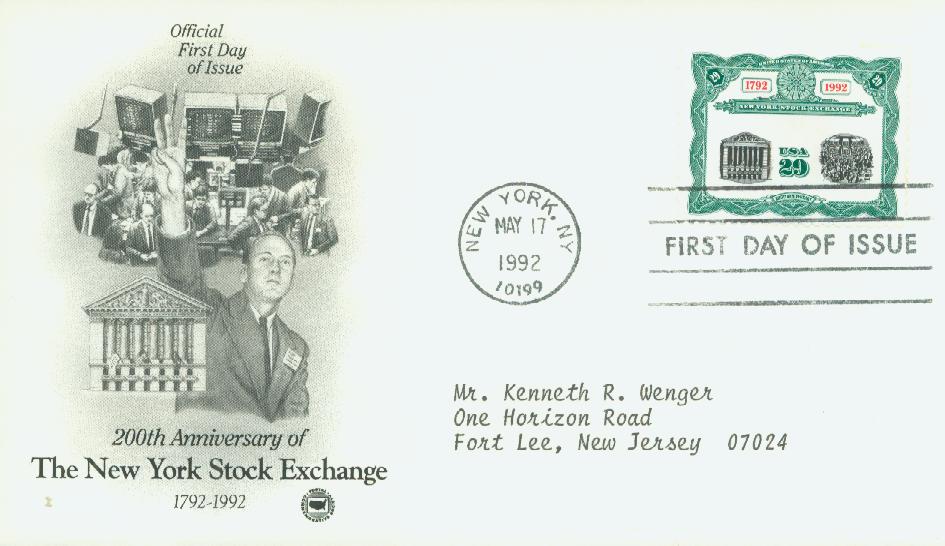

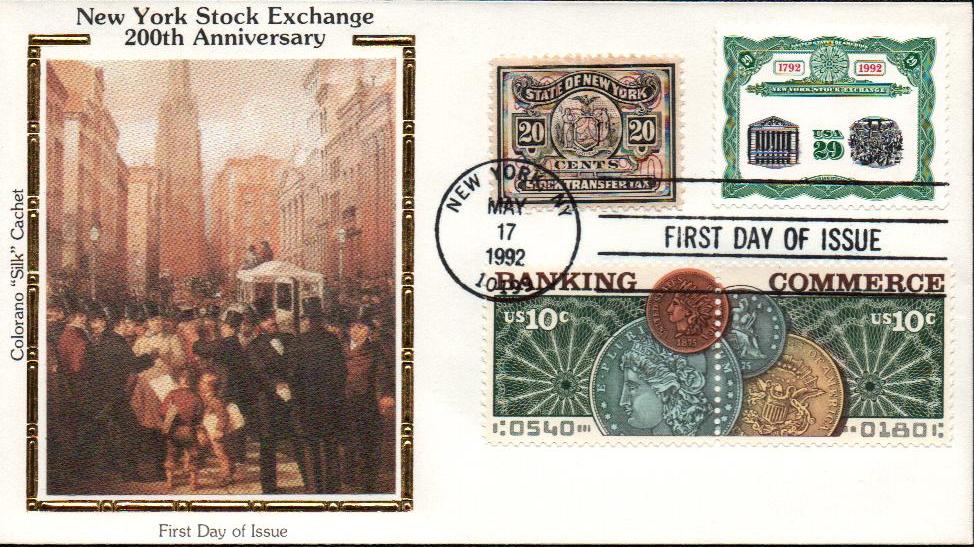

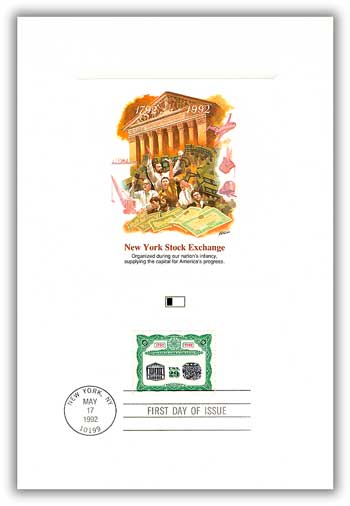

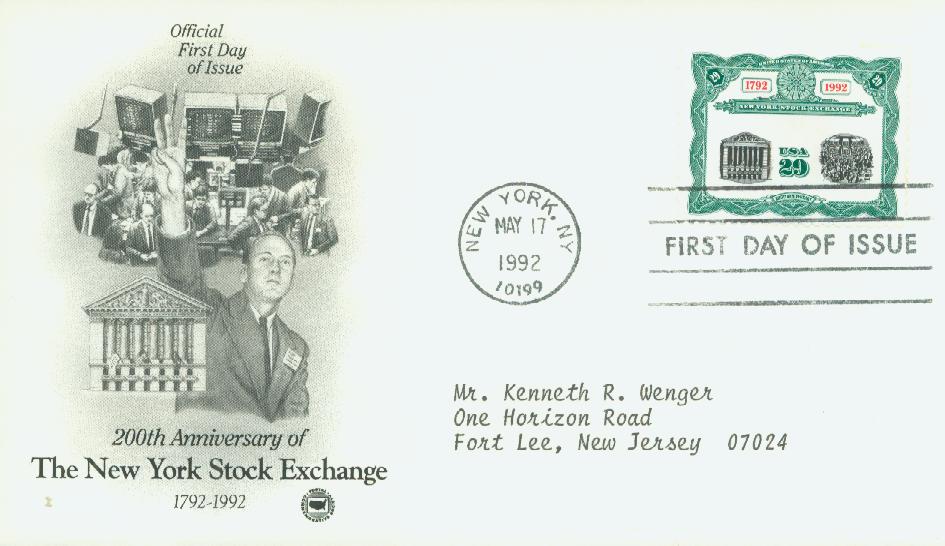

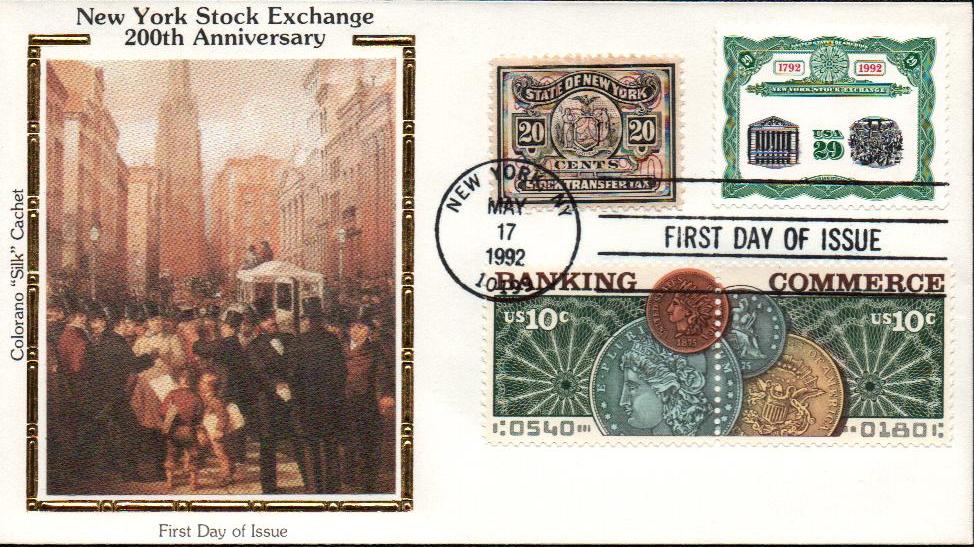

# 55972 FDC - 1992 New York Stock Exchange Proofcard

Often called the ultimate philatelic issue, the Fleetwood Proofcard is a distinctive commemorative with an elegantly embossed surface. Each Proofcard bears an original work of art complementing the theme of the stamp and created exclusively for Fleetwood by a leading American artist. Proofcards are often collected on their own, but would also make a beautiful addition to your existing stamp or cover collection.Â

Establishment Of The New York Stock Exchange

On March 8, 1817, the New York Stock Exchange was established out of a reorganization of stockbrokers working under the Buttonwood Agreement.

America’s investment markets were first born in 1790 when the federal government refinanced all state, federal, and Revolutionary War debt. They issued $80 million in bonds – the first publicly traded securities in America. In the early days, auctioneers often conducted these trades.

Two years later, on May 17, 1792, a group of 24 brokers and merchants met on New York City’s Wall Street to sign the Buttonwood Agreement. Signed under a buttonwood tree, the agreement stated that all the men would trade securities on a commission basis. With this, a .25% commission rate was set that would be charged to all clients. Additionally, the brokers agreed to only deal with each other, making the auctioneers obsolete in these transactions.

The agreement stated, “We the Subscribers, Brokers for the Purchase and Sale of the Public Stock, do hereby solemnly promise and pledge ourselves to each other, that we will not buy or sell from this day for any person whatsoever, any kind of Public Stock, at a less rate than one quarter percent Commission on the Specie value and that we will give preference to each other in our Negotiations. In Testimony whereof, we have set our hands this 17th day of May at New York, 1792.â€

With the end of the War of 1812 in 1815, the securities market in New York City began to grow. Bank and insurance stocks were added to government bonds as part of the trades. Two years later, the Buttonwood group sent members to observe the Philadelphia brokers. Following that, they met on March 8, 1817, and created new guidelines. Among these was the restriction of manipulative trading. They also adopted a new name: the New York Stock and Exchange Board (NYS&EB).

In the coming years, the NYS&EB grew, reaching a high of 380,000 shares in 1824. The following year, New York State bonds helped finance the Erie Canal and were actively traded on the NYS&EB floor. The NYS&EB hit another milestone in 1830 when it traded its first railroad stock, the Mohawk & Hudson.

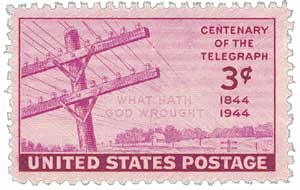

The first major drop at the NYS&EB came with the Panic of 1837 when the average daily volume dropped from 7,393 to 1,534 shares in six months. However, the nation recovered and the invention of the telegraph broadened the market’s reach beyond New York City in 1844.

After surviving another panic in 1857, the NYS&EB prohibited trade with seceded states at the outbreak of the Civil War. Then in 1863, the organization changes its name to the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE).

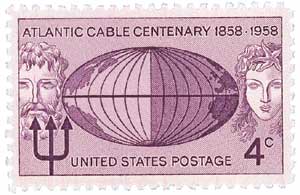

A major innovation came in 1866 with the completion of the first trans-Atlantic cable, providing instant communication between New York and London.  Another breakthrough came the following year when Edward A. Calahan introduced the stock ticker, delivering current prices to investors. The trading room floor received its first telephone in 1878, about two years after it was invented by Alexander Graham Bell.

The market grew so much that on December 15, 1886, the NYSE had its first of many million-share days. However, difficult days lay ahead. The Panic of 1893 saw stock prices drop dramatically, at the same time that 500 banks and 15,000 businesses failed. Though the economy recovered, a much larger financial disaster was on the horizon.

By the early 1920s, America was in an age of economic prosperity. Industry was booming, and Americans wanted to be a part of this economic surge. To accomplish this, they bought common stock on the open market, often borrowing money to do so. The average cost of each share more than doubled between 1925 and 1929, and market speculation increased. People purchased stock in hopes of future price increases.

The first clue that the market was overloaded came on October 24, 1929, now known as Black Thursday. Prices began to enter a slump, and investors became suspicious of a panic. Prices held Friday and Saturday but fell again Monday. On Tuesday, October 29th, the day of the stock market crash, more than 16 million shares changed hands. Investors sold stock at far less than they had paid. Some witnesses said that shares might have even been given away.

It was almost impossible to add up all the losses, as stunned brokers watched stock prices plummet. In fact, stocks were traded so fast that by the time the final bell sounded at three o’clock, the ticker was four hours behind. By the end of the day, trading had stabilized, but not in time to save billions of dollars. Stock values continued to fall steadily for the next three years, though the Great Depression would last much longer.

The market eventually recovered and has had its ups and downs in the decades since. Today, the NYSE is the world’s largest stock exchange, with its trading numbering over $19 trillion.

Click here to view photos of the NYSE through the years.

Often called the ultimate philatelic issue, the Fleetwood Proofcard is a distinctive commemorative with an elegantly embossed surface. Each Proofcard bears an original work of art complementing the theme of the stamp and created exclusively for Fleetwood by a leading American artist. Proofcards are often collected on their own, but would also make a beautiful addition to your existing stamp or cover collection.Â

Establishment Of The New York Stock Exchange

On March 8, 1817, the New York Stock Exchange was established out of a reorganization of stockbrokers working under the Buttonwood Agreement.

America’s investment markets were first born in 1790 when the federal government refinanced all state, federal, and Revolutionary War debt. They issued $80 million in bonds – the first publicly traded securities in America. In the early days, auctioneers often conducted these trades.

Two years later, on May 17, 1792, a group of 24 brokers and merchants met on New York City’s Wall Street to sign the Buttonwood Agreement. Signed under a buttonwood tree, the agreement stated that all the men would trade securities on a commission basis. With this, a .25% commission rate was set that would be charged to all clients. Additionally, the brokers agreed to only deal with each other, making the auctioneers obsolete in these transactions.

The agreement stated, “We the Subscribers, Brokers for the Purchase and Sale of the Public Stock, do hereby solemnly promise and pledge ourselves to each other, that we will not buy or sell from this day for any person whatsoever, any kind of Public Stock, at a less rate than one quarter percent Commission on the Specie value and that we will give preference to each other in our Negotiations. In Testimony whereof, we have set our hands this 17th day of May at New York, 1792.â€

With the end of the War of 1812 in 1815, the securities market in New York City began to grow. Bank and insurance stocks were added to government bonds as part of the trades. Two years later, the Buttonwood group sent members to observe the Philadelphia brokers. Following that, they met on March 8, 1817, and created new guidelines. Among these was the restriction of manipulative trading. They also adopted a new name: the New York Stock and Exchange Board (NYS&EB).

In the coming years, the NYS&EB grew, reaching a high of 380,000 shares in 1824. The following year, New York State bonds helped finance the Erie Canal and were actively traded on the NYS&EB floor. The NYS&EB hit another milestone in 1830 when it traded its first railroad stock, the Mohawk & Hudson.

The first major drop at the NYS&EB came with the Panic of 1837 when the average daily volume dropped from 7,393 to 1,534 shares in six months. However, the nation recovered and the invention of the telegraph broadened the market’s reach beyond New York City in 1844.

After surviving another panic in 1857, the NYS&EB prohibited trade with seceded states at the outbreak of the Civil War. Then in 1863, the organization changes its name to the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE).

A major innovation came in 1866 with the completion of the first trans-Atlantic cable, providing instant communication between New York and London.  Another breakthrough came the following year when Edward A. Calahan introduced the stock ticker, delivering current prices to investors. The trading room floor received its first telephone in 1878, about two years after it was invented by Alexander Graham Bell.

The market grew so much that on December 15, 1886, the NYSE had its first of many million-share days. However, difficult days lay ahead. The Panic of 1893 saw stock prices drop dramatically, at the same time that 500 banks and 15,000 businesses failed. Though the economy recovered, a much larger financial disaster was on the horizon.

By the early 1920s, America was in an age of economic prosperity. Industry was booming, and Americans wanted to be a part of this economic surge. To accomplish this, they bought common stock on the open market, often borrowing money to do so. The average cost of each share more than doubled between 1925 and 1929, and market speculation increased. People purchased stock in hopes of future price increases.

The first clue that the market was overloaded came on October 24, 1929, now known as Black Thursday. Prices began to enter a slump, and investors became suspicious of a panic. Prices held Friday and Saturday but fell again Monday. On Tuesday, October 29th, the day of the stock market crash, more than 16 million shares changed hands. Investors sold stock at far less than they had paid. Some witnesses said that shares might have even been given away.

It was almost impossible to add up all the losses, as stunned brokers watched stock prices plummet. In fact, stocks were traded so fast that by the time the final bell sounded at three o’clock, the ticker was four hours behind. By the end of the day, trading had stabilized, but not in time to save billions of dollars. Stock values continued to fall steadily for the next three years, though the Great Depression would last much longer.

The market eventually recovered and has had its ups and downs in the decades since. Today, the NYSE is the world’s largest stock exchange, with its trading numbering over $19 trillion.

Click here to view photos of the NYSE through the years.