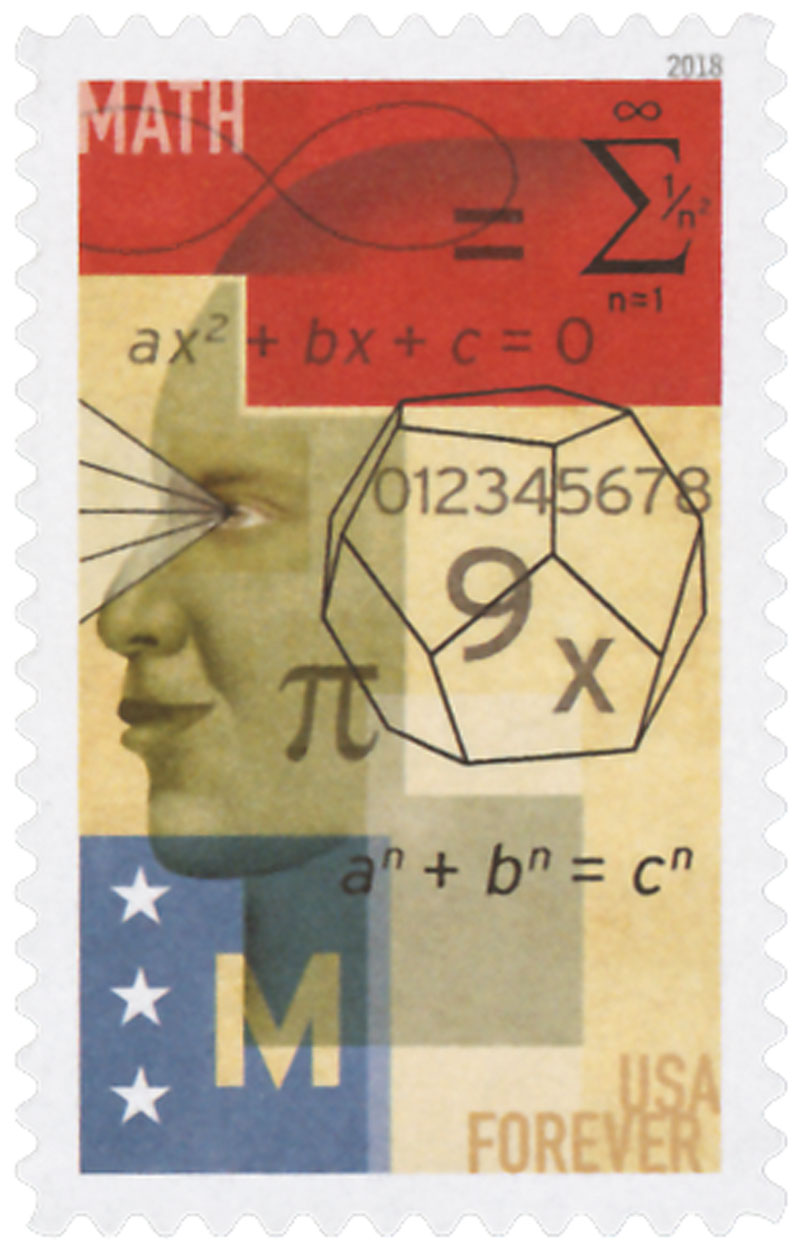

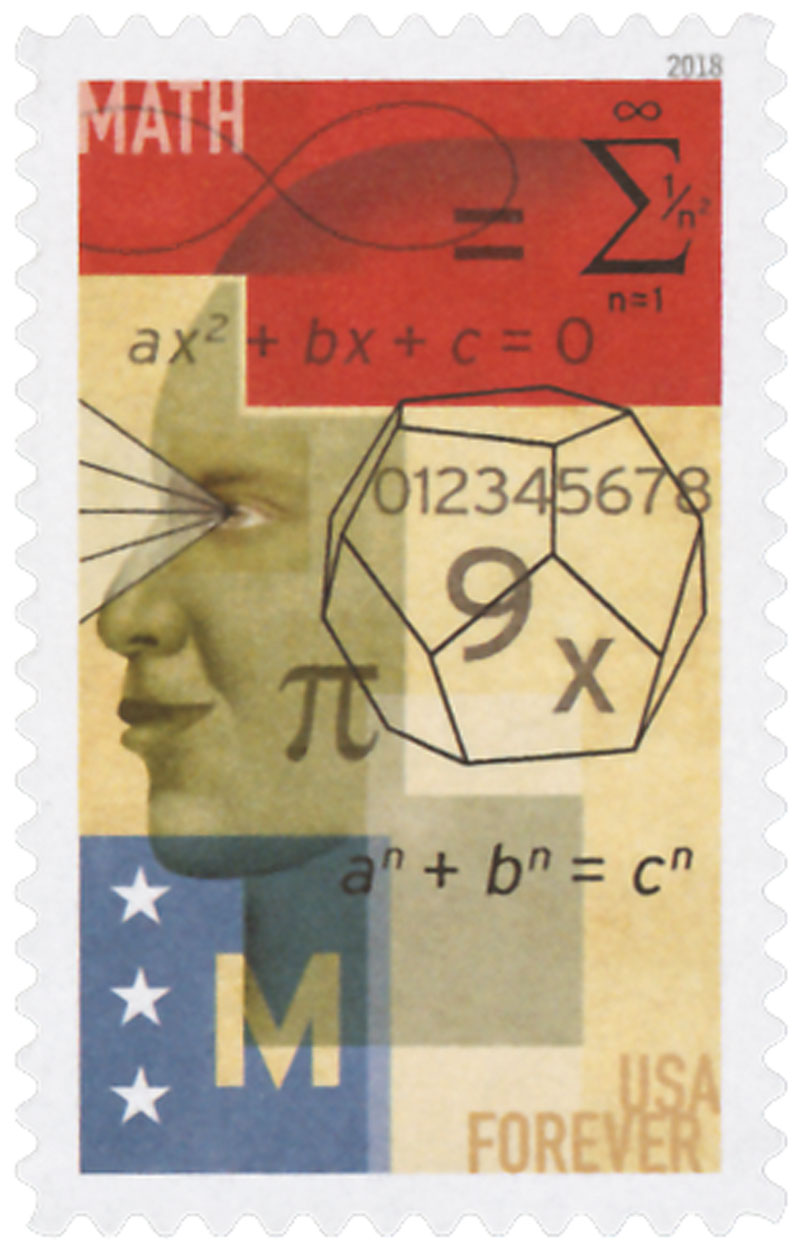

# 5279 - 2018 First-Class Forever Stamp - STEM Education: Math

#5279 - Mathematics

2018 50c STEM Education

Value: 50¢ 1-ounce first-class letter rate- Forever

Issued: April 6, 2018

First Day City: Washington, DC

Type of Stamp: Commemorative

Printed by: Ashton Potter

Method: Offset

Format: Pane of 20

Self-Adhesive

Quantity Printed: 15,000,000 stamps

Mathematics plays an often-unnoticed part in our everyday lives. But nearly everything we do involves a calculation of some sort. And most children rarely consider a career in math. If they looked at those who came before them, they might see all the amazing and important work mathematicians do.

Benjamin Banneker was a self-educated inventor, mathematician, astronomer, and surveyor. He enjoyed mathematical puzzles, which he used to build a clock that maintained the correct time for decades. Banneker used astronomical calculations to predict the 1789 solar eclipse, proving well-known astronomers wrong. For several years, he calculated the locations of planets and stars, which he published in an almanac.

Another pioneer was Emmy Noether, who has been called “the greatest woman mathematician of all time.” Despite the obstacles she faced as a woman in early academia, Noether was driven by her love for math and made major advances in algebra. Most notably, she developed Noether’s theorem, which explains the connection between symmetry and conservation laws. Her theorem is an important part of modern physics.

The idea of a career in mathematics can seem challenging to some children. It is important for them to look to figures such as Banneker and Noether and see what a profound effect they can have on the world.

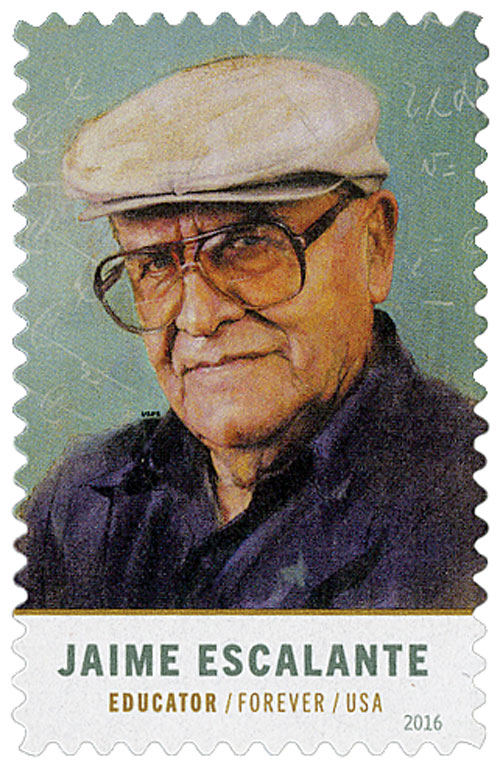

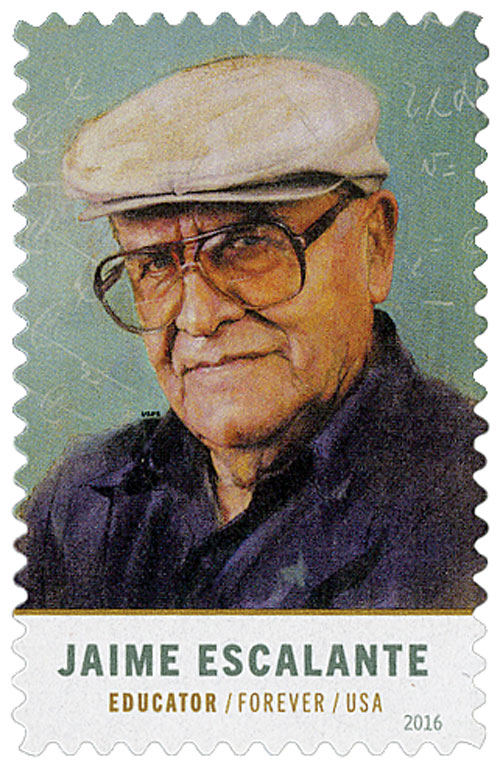

Birth of Jaime Escalante

Jaime Alfonso Escalante Gutiérrez was born on December 31, 1930, in La Paz, Bolivia. Escalante taught math to a class of students previously deemed “unteachable.” Escalante became famous after the story of his success was re-told in a book and a movie. Both of Escalante’s parents were teachers and he went to school for the same profession. He taught physics and math in Bolivia for 12 years before moving to the United States in the 1960s. He worked odd jobs, taught himself English, and earned degrees from California State University so he could teach in America. In 1974, Escalante began teaching at Los Angeles’s Garfield High School. Many of the school’s students were considered “unteachable,” but Escalante knew that with hard work, they could flourish. He created an Advanced Placement calculus class and pushed his 12 students to succeed. Escalante told them that math would be their language and with this education, they could work in engineering, electronics, and computers. One of the students claimed, “If he wants to teach us that bad, we can learn.” The school’s principal at the time opposed Escalante’s methods. Escalante made students answer math questions before allowing them to enter the classroom. The principal told him to just let the students in, but Escalante criticized the school, saying, “There is no teaching, no learning going on here. We are just baby-sitting.” Escalante came in early and stayed late and raised money to pay for the students to take Advanced Placement tests. The school threatened to fire him over this, but never did. When a new principal came in, he supported Escalante’s mission and made major changes to the school’s curriculum. He cut down the number of basic math classes and made algebra a requirement. He also prevented students from participating in extracurricular activities if they failed their tests. In 1978, Escalante began teaching calculus to five students. By 1982, the calculus class increased to 18 students. When they all passed the test that year, the testing service became suspicious. Fourteen students were asked to retake the test, which twelve did. All twelve passed again and were able to have their grade reinstated. Escalante’s calculus class more than doubled in size the following year to 33 students. He also started teaching calculus at East Los Angeles College. In 1988, author Jay Matthews published the book, Escalante: The Best Teacher in America, based on the story of the 1982 calculus class. That same year, a film based on the story was released as well: Stand and Deliver, starring Edward James Olmos. Escalante said the film was “90% truth, 10% drama.” The book and film made Escalante a national figure. Soon teachers and other visitors sat in on his classes and he received visits from President Ronald Reagan and actor Arnold Schwarzenegger. Escalante’s math program grew dramatically in the next few years. He had over 400 students with more than 50 students in each class, exceeding the 35 student limit established by the teachers’ union. Over time, Garfield sent more students to the local college than any other area high school. However, Escalante had his share of critics and left the school in 1991. He went on to teach at Hiram W. Johnson High School. Garfield’s calculus program floundered after Escalante left. Escalante continued teaching in the US until 2001. He returned to Bolivia to teach at the Universidad Privada del Valle but eventually moved back to the US. In his later years, Escalante suffered from cancer and struggled financially to pay for his treatments. Cast members from Stand and Deliver as well as former students raised money to help pay his bills. Escalante died on March 30, 2010, from bladder cancer. He received many honors during and after his lifetime, including the Presidential Medal of Excellence in Education, several honorary degrees, and induction into the National Teachers Hall of Fame. But his greatest reward was his students’ success. As he put it, “teaching is touching life.” Escalante also has a school and asteroid named after him.

#5279 - Mathematics

2018 50c STEM Education

Value: 50¢ 1-ounce first-class letter rate- Forever

Issued: April 6, 2018

First Day City: Washington, DC

Type of Stamp: Commemorative

Printed by: Ashton Potter

Method: Offset

Format: Pane of 20

Self-Adhesive

Quantity Printed: 15,000,000 stamps

Mathematics plays an often-unnoticed part in our everyday lives. But nearly everything we do involves a calculation of some sort. And most children rarely consider a career in math. If they looked at those who came before them, they might see all the amazing and important work mathematicians do.

Benjamin Banneker was a self-educated inventor, mathematician, astronomer, and surveyor. He enjoyed mathematical puzzles, which he used to build a clock that maintained the correct time for decades. Banneker used astronomical calculations to predict the 1789 solar eclipse, proving well-known astronomers wrong. For several years, he calculated the locations of planets and stars, which he published in an almanac.

Another pioneer was Emmy Noether, who has been called “the greatest woman mathematician of all time.” Despite the obstacles she faced as a woman in early academia, Noether was driven by her love for math and made major advances in algebra. Most notably, she developed Noether’s theorem, which explains the connection between symmetry and conservation laws. Her theorem is an important part of modern physics.

The idea of a career in mathematics can seem challenging to some children. It is important for them to look to figures such as Banneker and Noether and see what a profound effect they can have on the world.

Birth of Jaime Escalante

Jaime Alfonso Escalante Gutiérrez was born on December 31, 1930, in La Paz, Bolivia. Escalante taught math to a class of students previously deemed “unteachable.” Escalante became famous after the story of his success was re-told in a book and a movie. Both of Escalante’s parents were teachers and he went to school for the same profession. He taught physics and math in Bolivia for 12 years before moving to the United States in the 1960s. He worked odd jobs, taught himself English, and earned degrees from California State University so he could teach in America. In 1974, Escalante began teaching at Los Angeles’s Garfield High School. Many of the school’s students were considered “unteachable,” but Escalante knew that with hard work, they could flourish. He created an Advanced Placement calculus class and pushed his 12 students to succeed. Escalante told them that math would be their language and with this education, they could work in engineering, electronics, and computers. One of the students claimed, “If he wants to teach us that bad, we can learn.” The school’s principal at the time opposed Escalante’s methods. Escalante made students answer math questions before allowing them to enter the classroom. The principal told him to just let the students in, but Escalante criticized the school, saying, “There is no teaching, no learning going on here. We are just baby-sitting.” Escalante came in early and stayed late and raised money to pay for the students to take Advanced Placement tests. The school threatened to fire him over this, but never did. When a new principal came in, he supported Escalante’s mission and made major changes to the school’s curriculum. He cut down the number of basic math classes and made algebra a requirement. He also prevented students from participating in extracurricular activities if they failed their tests. In 1978, Escalante began teaching calculus to five students. By 1982, the calculus class increased to 18 students. When they all passed the test that year, the testing service became suspicious. Fourteen students were asked to retake the test, which twelve did. All twelve passed again and were able to have their grade reinstated. Escalante’s calculus class more than doubled in size the following year to 33 students. He also started teaching calculus at East Los Angeles College. In 1988, author Jay Matthews published the book, Escalante: The Best Teacher in America, based on the story of the 1982 calculus class. That same year, a film based on the story was released as well: Stand and Deliver, starring Edward James Olmos. Escalante said the film was “90% truth, 10% drama.” The book and film made Escalante a national figure. Soon teachers and other visitors sat in on his classes and he received visits from President Ronald Reagan and actor Arnold Schwarzenegger. Escalante’s math program grew dramatically in the next few years. He had over 400 students with more than 50 students in each class, exceeding the 35 student limit established by the teachers’ union. Over time, Garfield sent more students to the local college than any other area high school. However, Escalante had his share of critics and left the school in 1991. He went on to teach at Hiram W. Johnson High School. Garfield’s calculus program floundered after Escalante left. Escalante continued teaching in the US until 2001. He returned to Bolivia to teach at the Universidad Privada del Valle but eventually moved back to the US. In his later years, Escalante suffered from cancer and struggled financially to pay for his treatments. Cast members from Stand and Deliver as well as former students raised money to help pay his bills. Escalante died on March 30, 2010, from bladder cancer. He received many honors during and after his lifetime, including the Presidential Medal of Excellence in Education, several honorary degrees, and induction into the National Teachers Hall of Fame. But his greatest reward was his students’ success. As he put it, “teaching is touching life.” Escalante also has a school and asteroid named after him.