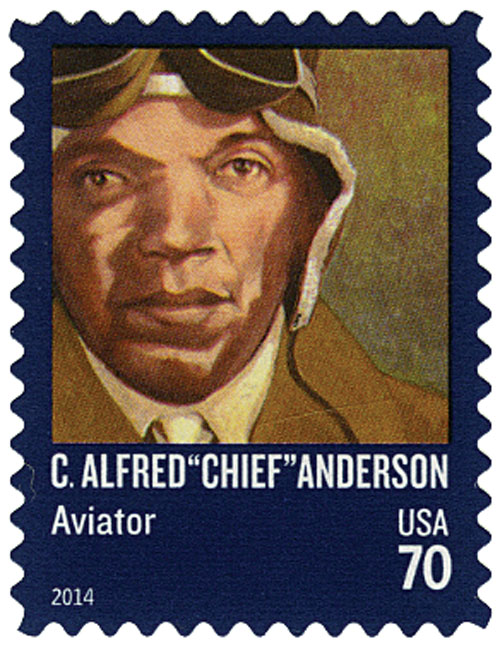

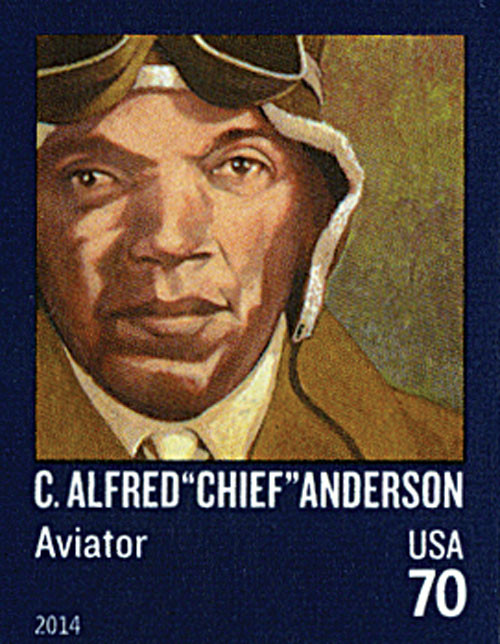

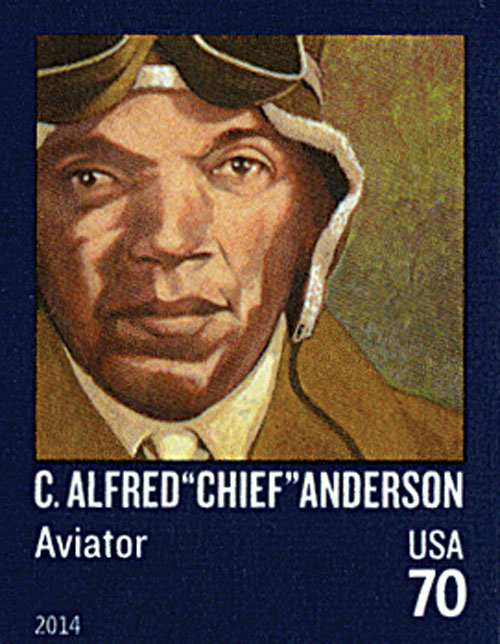

# 4879a FDC - 2014 70c Imperf C. Alfred Anderson

U.S. #4879a

2014 70¢ C. Alfred “Chief†Anderson Imperforate

Distinguished Americans Series

Â

Â

Â

Â

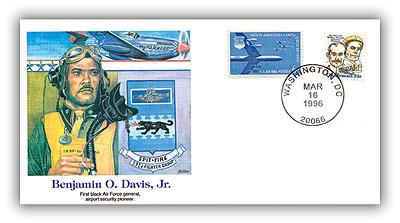

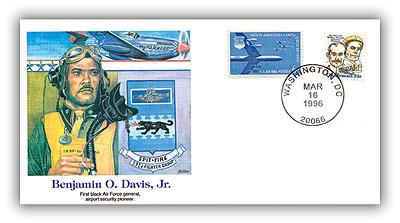

The Father of Black Aviation, Charles Alfred “Chief†Anderson Sr. was born on February 9, 1907, in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. As a child in Pennsylvania, Anderson watched airplanes soar across the sky and knew he wanted to be in the cockpit one day. After high school, he could not find anyone willing to rent him a plane or teach him to fly because of the color of his skin. Anderson didn’t give up though. He went to aviation ground school and learned about the mechanics of airplanes. He also spent time at airports, learning whatever he could from the pilots. By 1929, Anderson realized the only way he would get to fly was to buy his own plane. That’s just what he did – he purchased a Velie Monocoupe with his savings and money loaned from friends and family. He joined a flying club, but they didn’t teach him. Over time, Anderson taught himself to take off and land the plane. Eventually Anderson was able to make a deal with one of the club members. Russell Thaw wanted to visit his mother in Atlantic City on weekends but didn’t have his own plane. Thaw would fly Anderson’s plane while Anderson watched. By August 1929, Anderson was able to get his private pilot’s license. When Anderson next set out to get an air transport pilot’s license, he again had trouble finding someone willing to train him. Eventually, he met Ernest H. Buehl, a German pilot who helped open transcontinental airmail routes. With Buehl’s training, Anderson got his license in February 1932. He was the first African American to get an air transport pilot’s license from the Civil Aeronautics Administration. In 1933, Anderson met doctor and fellow pilot Albert E. Forsythe. Together they set out to encourage more African Americans to become pilots. They did so in part by making record-setting flights. They became the first black pilots to make a round-trip flight across the US. Anderson and Forsythe also flew a goodwill tour of the Caribbean. By 1938, Anderson was an aviation instructor in Washington, DC. As World War II raged in Europe, America prepared for combat. In 1940, Anderson was hired to be chief flight instructor at the Tuskegee Institute’s new Civilian Pilot Training Program. Anderson developed the pilot training program and taught the first advanced course. It was here he earned his nickname, “Chief.â€Â He also taught some aviation pioneers including Benjamin O. Davis Jr and Daniel “Chappie†James Sr. In 1941, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the institute and took a 40-minute flight with Anderson. Later that year, the Army made Anderson Tuskegee’s ground commander and chief instructor of the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the first all-African American fighter squadron. By the war’s end, Anderson had trained nearly 1,000 pilots. The Tuskegee Airmen flew 1,378 combat missions and earned more than 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses and other awards. After the war, Anderson continued to teach at the institute. In 1967, he helped found Negro Airmen International, the oldest African American pilot organization in the country. Anderson’s health declined by the 1990s and he could no longer fly. He died on April 13, 1996. His family later founded the C. Alfred “Chief†Anderson Legacy Foundation to continue his mission of promoting aviation to children and communities.Happy Birthday, Alfred “Chief†Anderson

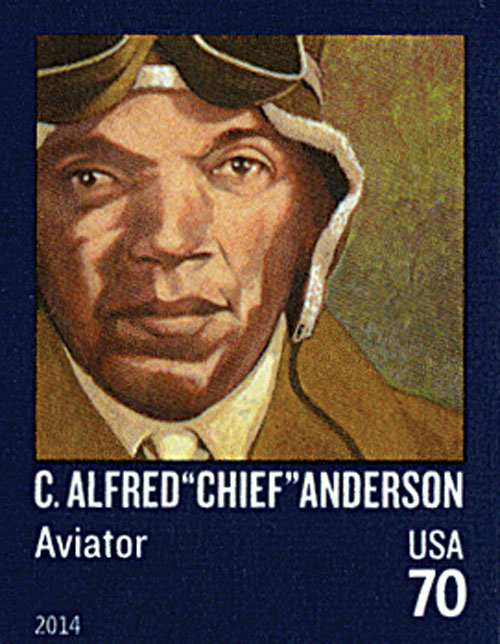

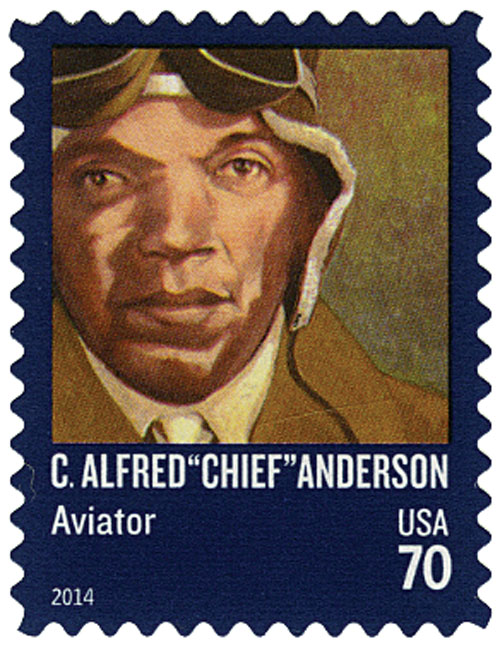

U.S. #4879a

2014 70¢ C. Alfred “Chief†Anderson Imperforate

Distinguished Americans Series

Â

Â

Â

Â

The Father of Black Aviation, Charles Alfred “Chief†Anderson Sr. was born on February 9, 1907, in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. As a child in Pennsylvania, Anderson watched airplanes soar across the sky and knew he wanted to be in the cockpit one day. After high school, he could not find anyone willing to rent him a plane or teach him to fly because of the color of his skin. Anderson didn’t give up though. He went to aviation ground school and learned about the mechanics of airplanes. He also spent time at airports, learning whatever he could from the pilots. By 1929, Anderson realized the only way he would get to fly was to buy his own plane. That’s just what he did – he purchased a Velie Monocoupe with his savings and money loaned from friends and family. He joined a flying club, but they didn’t teach him. Over time, Anderson taught himself to take off and land the plane. Eventually Anderson was able to make a deal with one of the club members. Russell Thaw wanted to visit his mother in Atlantic City on weekends but didn’t have his own plane. Thaw would fly Anderson’s plane while Anderson watched. By August 1929, Anderson was able to get his private pilot’s license. When Anderson next set out to get an air transport pilot’s license, he again had trouble finding someone willing to train him. Eventually, he met Ernest H. Buehl, a German pilot who helped open transcontinental airmail routes. With Buehl’s training, Anderson got his license in February 1932. He was the first African American to get an air transport pilot’s license from the Civil Aeronautics Administration. In 1933, Anderson met doctor and fellow pilot Albert E. Forsythe. Together they set out to encourage more African Americans to become pilots. They did so in part by making record-setting flights. They became the first black pilots to make a round-trip flight across the US. Anderson and Forsythe also flew a goodwill tour of the Caribbean. By 1938, Anderson was an aviation instructor in Washington, DC. As World War II raged in Europe, America prepared for combat. In 1940, Anderson was hired to be chief flight instructor at the Tuskegee Institute’s new Civilian Pilot Training Program. Anderson developed the pilot training program and taught the first advanced course. It was here he earned his nickname, “Chief.â€Â He also taught some aviation pioneers including Benjamin O. Davis Jr and Daniel “Chappie†James Sr. In 1941, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the institute and took a 40-minute flight with Anderson. Later that year, the Army made Anderson Tuskegee’s ground commander and chief instructor of the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the first all-African American fighter squadron. By the war’s end, Anderson had trained nearly 1,000 pilots. The Tuskegee Airmen flew 1,378 combat missions and earned more than 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses and other awards. After the war, Anderson continued to teach at the institute. In 1967, he helped found Negro Airmen International, the oldest African American pilot organization in the country. Anderson’s health declined by the 1990s and he could no longer fly. He died on April 13, 1996. His family later founded the C. Alfred “Chief†Anderson Legacy Foundation to continue his mission of promoting aviation to children and communities.Happy Birthday, Alfred “Chief†Anderson