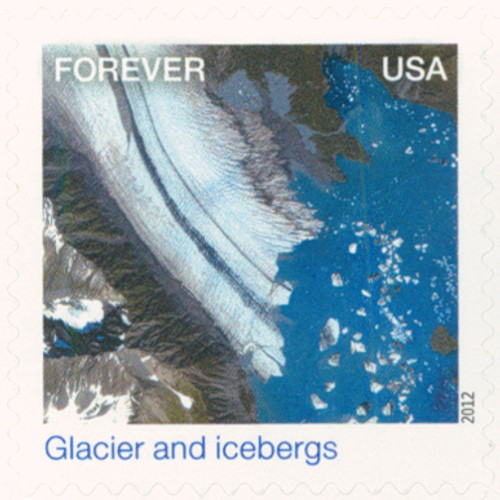

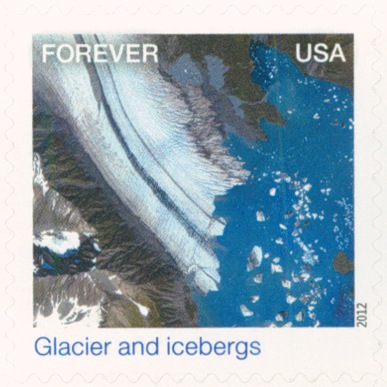

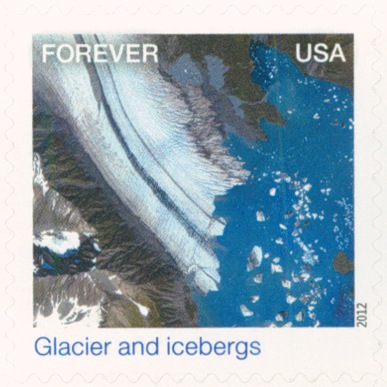

# 4710a - 2012 First-Class Forever Stamp - Earthscapes: Glacier and Icebergs

2012 45¢ Glacier and Icebergs

Earthscapes

City: Washington, DC

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve

On December 2, 1980, President Jimmy Carter established Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve in Alaska. Today the park is part of one of the world’s largest international protected areas.

The earliest records of human activity in the Glacier Bay area date back about 10,000 years. Advancing glaciers have likely concealed more signs of human occupation. It’s believed the Haida, Eyak, and Tlingit lived along the coast during this early era, with the Tlingit eventually becoming the most prominent group. Russian fur traders are thought to have visited the area in the mid-1700s and Jean-Francois de Galaup was the first known European to explore the area.

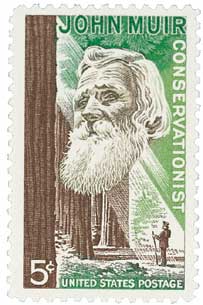

In 1879, naturalist and “father” of Yosemite National Park John Muir visited Glacier Bay, Alaska. He wanted to study an active glacier to help him understand the glaciated landscape in Yosemite Valley. His research brought attention to the Alaskan coast, and soon scientists and tourists were visiting the bay to see the famous Muir Glacier named in his honor.

In the 1890s, the Pacific Coast Steamship Company began offering tours to the area. Soon naturalists and geologists came to survey and name the glaciers. Muir joined in the Harriman Alaska Expedition of 1899, along with George Bird Grinnell and Edward S. Curtis. They spent five days at Glacier Bay, during which time they recorded significant glacial retreat. Then on September 10, 1899, an earthquake sent the Muir Glacier crashing into the water. Tourism in the area waned after that.

However, ecologist William Skinner Cooper had become interested in the area due to Muir’s writing. Starting in 1916, he used the retreating glaciers to study plant succession on the newly exposed ground – and he recognized the need to protect it. He wrote a paper on his findings for the Ecological Society of America in 1922 and recommended Glacier Bay be preserved as a national monument. The society agreed and began to actively campaign for national monument status. After extensive lobbying, they succeeded when President Calvin Coolidge established Glacier Bay National Monument on February 26, 1925.

Not long after, it was proposed that the monument be expanded to protect Alaska brown bears. On April 18, 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt expanded the monument, making it the largest unit in the national park system up to that time. The park was expanded again in 1978 to include the Alsek Islands. Then on December 2, 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed a law converting almost 3.3 million acres to Glacier Bay National Park, with 57,000 acres designated as a preserve.

The park is part of the Kluane-Wrangell-St. Elias-Glacier Bay-Tatshenshini-Alsek transborder park system and was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979. This designation came for both its glaciers and icefields as well as its protection of grizzly bears, caribou, and Dall sheep. More than half a million people visit the park every year. Scientists continue to take advantage of the changing landscape in what they now refer to as a “living laboratory.”

2012 45¢ Glacier and Icebergs

Earthscapes

City: Washington, DC

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve

On December 2, 1980, President Jimmy Carter established Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve in Alaska. Today the park is part of one of the world’s largest international protected areas.

The earliest records of human activity in the Glacier Bay area date back about 10,000 years. Advancing glaciers have likely concealed more signs of human occupation. It’s believed the Haida, Eyak, and Tlingit lived along the coast during this early era, with the Tlingit eventually becoming the most prominent group. Russian fur traders are thought to have visited the area in the mid-1700s and Jean-Francois de Galaup was the first known European to explore the area.

In 1879, naturalist and “father” of Yosemite National Park John Muir visited Glacier Bay, Alaska. He wanted to study an active glacier to help him understand the glaciated landscape in Yosemite Valley. His research brought attention to the Alaskan coast, and soon scientists and tourists were visiting the bay to see the famous Muir Glacier named in his honor.

In the 1890s, the Pacific Coast Steamship Company began offering tours to the area. Soon naturalists and geologists came to survey and name the glaciers. Muir joined in the Harriman Alaska Expedition of 1899, along with George Bird Grinnell and Edward S. Curtis. They spent five days at Glacier Bay, during which time they recorded significant glacial retreat. Then on September 10, 1899, an earthquake sent the Muir Glacier crashing into the water. Tourism in the area waned after that.

However, ecologist William Skinner Cooper had become interested in the area due to Muir’s writing. Starting in 1916, he used the retreating glaciers to study plant succession on the newly exposed ground – and he recognized the need to protect it. He wrote a paper on his findings for the Ecological Society of America in 1922 and recommended Glacier Bay be preserved as a national monument. The society agreed and began to actively campaign for national monument status. After extensive lobbying, they succeeded when President Calvin Coolidge established Glacier Bay National Monument on February 26, 1925.

Not long after, it was proposed that the monument be expanded to protect Alaska brown bears. On April 18, 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt expanded the monument, making it the largest unit in the national park system up to that time. The park was expanded again in 1978 to include the Alsek Islands. Then on December 2, 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed a law converting almost 3.3 million acres to Glacier Bay National Park, with 57,000 acres designated as a preserve.

The park is part of the Kluane-Wrangell-St. Elias-Glacier Bay-Tatshenshini-Alsek transborder park system and was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979. This designation came for both its glaciers and icefields as well as its protection of grizzly bears, caribou, and Dall sheep. More than half a million people visit the park every year. Scientists continue to take advantage of the changing landscape in what they now refer to as a “living laboratory.”