# 4510 FDC - 2011 84c Oveta Culp Hobby

U.S. #4510

2011 84¢ Oveta Culp Hobby

Issue Date: April 15, 2011

City: Houston, TX

Printed By: Avery Dennison

Printing Method: Photogravure

Color: Multicolored

“Women who stepped up were measured as

citizens of the nation, not as women...

This was a people’s war, and everyone was in it.”

– Oveta Culp Hobby

Oveta Culp Hobby (1905-95) responded when called upon to serve her country. In the process, she created new opportunities for women, helped the Allies win World War II, and approved a drug that virtually eliminated polio in the United States.

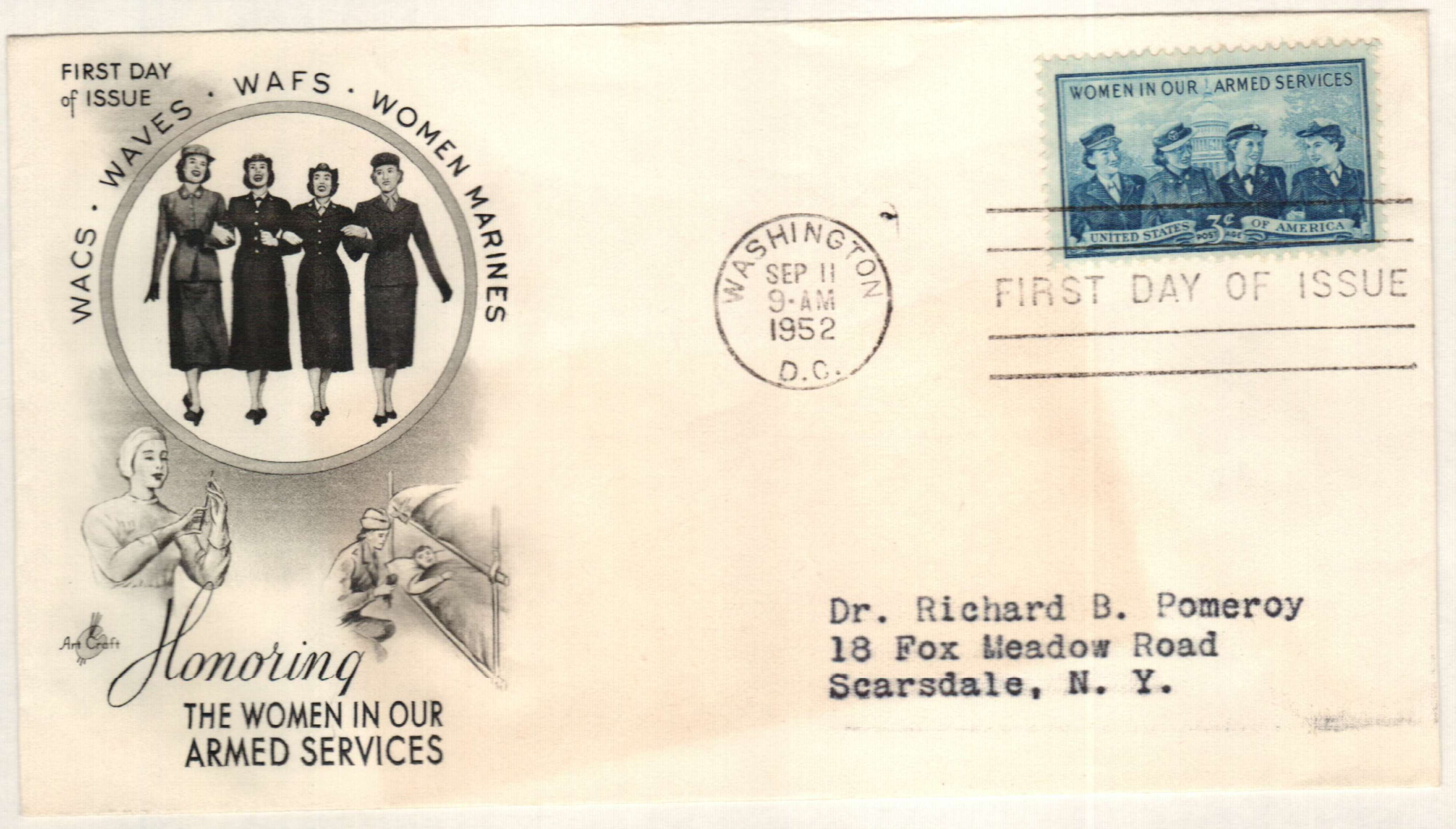

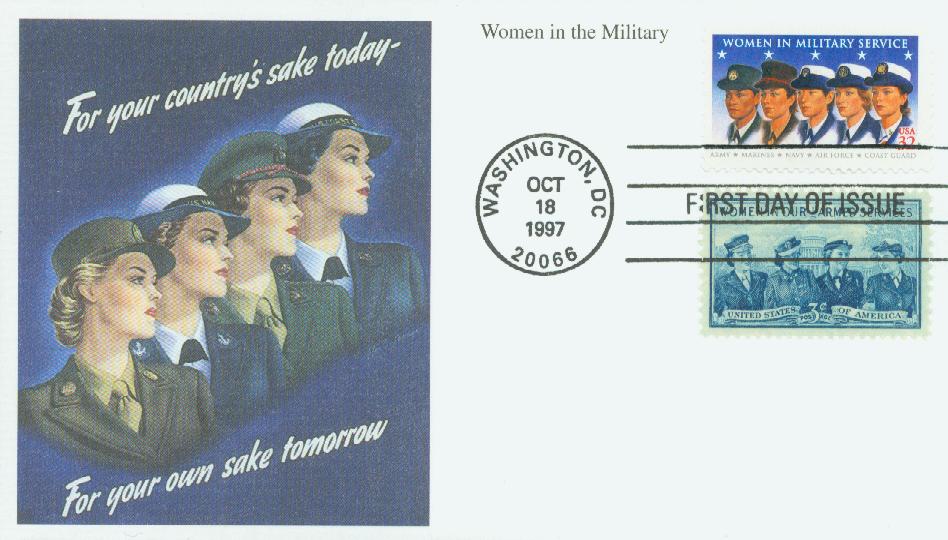

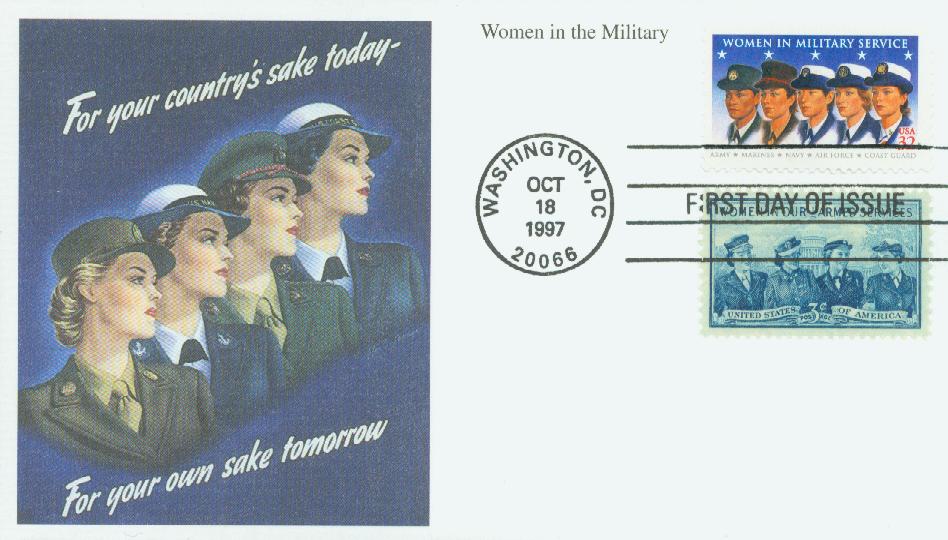

During World War II, Hobby became the Director of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, created to remedy severe labor shortages caused by men serving in the war effort. Its members, who were the first women other than nurses to be in Army uniform, helped the U.S. meet the industrial demands needed to win the war. Although she “never did learn to salute properly or master the 30-inch stride,” Colonel Oveta Hobby became the first woman in the Army to receive the Distinguished Service Medal.

President Dwight Eisenhower named Hobby the first secretary of the new Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Hobby personally made the decision to approve Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine. She resigned her position in 1955 to care for her ailing husband. Oveta died in 1995, knowing she had helped save two generations of Americans from the paralyzing effects of polio.

Formation Of WAAC

Prior to and at the start of World War II, women were generally only allowed on the battlefield as nurses or as volunteers as communications specialists or dieticians. Though they served with the Army, they didn’t have any official status, so they had to pay for their own food and lodging and didn’t receive any disability benefits or pensions when they returned home.

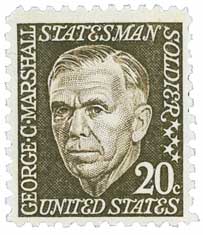

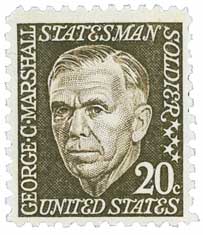

Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers knew all about this situation and was determined to get women the same protection and benefits as men if they were to be called on again. In early 1941, she met with General George C. Marshall the Army’s Chief of Staff, and told him of her plans to introduce a bill to create a women’s corps that was separate from the Nurse Corps.

Over time, the idea of a women’s corps gained support. However, while Rogers wanted to create an organization that was part of the army with equal pay, pension, and disability benefits, the Army was uneasy about accepting women right into its ranks. The resulting bill was a compromise. It would provide food, uniforms, living quarters, pay, and medical care for up to 150,000 women. However, the women would receive less pay than men of the same rank and didn’t receive overseas pay, government life insurance, veteran’s medical coverage, or protection if they were captured by enemy troops. Rogers had to give up some of her goals in order to get the bill onto the floor.

Rogers first introduced the bill in May 1941, but it didn’t receive much attention. It wasn’t until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that the bill was more seriously considered. General Marshall spoke out actively in favor of the bill. America was entering a two-front war and needed all the help it could get. The bill faced serious opposition, especially from southern congressmen, who asked “Who will then do the cooking, the washing, the mending, the humble homey tasks to which every woman has devoted herself; who will nurture the children?”

After significant debate, the House and Senate passed Rogers’ bill, which President Franklin Roosevelt signed into law on May 15, 1942. He initially set the recruitment goal at 25,000. That was met by November, after which time it was increased to 150,000.

The same day the bill was approved, Oveta Culp Hobby was made director of the WAAC. Hobby had worked as a newspaper editor and worked on the Texas legislature before speaking out in favor of the WAAC. Her first priority was recruiting women to serve as clerical workers, teachers, stenographers, and telephone operators. Every woman she recruited would “free a man for combat.” As Hobby explained, “The gaps our women will fill are in those noncombatant jobs where women’s hands and women’s hearts fit naturally. WAACs will do the same type of work which women do in civilian life. They will bear the same relation to men of the Army that they bear to the men of the civilian organizations in which they work.”

The first batch of officer recruits were an average age of 25 years old, most of whom attended college and worked in an office or as a teacher. One in five enlisted because a male family member was serving and they wanted to help him get home faster.

After extensive training, the first WAAC units were put to work with Aircraft Warning Service units. By October, there were 27 WAAC companies at these stations up and down the eastern seaboard. Soon other WAACs were assigned to the Army Air Forces, Army Ground Forces, or Army Services Forces. As time went on, the WAACs duties expanded significantly. By the last year of the war, only about half of the WAACs were performing traditional jobs. Other tasks included weather observers, cryptographers, repairs, parachute riggers, photograph analysts, control tower operations, electricians, and radio operators, among many other things.

As American military planners began looking toward another front in Europe, they realized a need for more manpower. Out of this need, talks began of creating the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), which would be a part of the Army, and not just serving with it. The WAC would also offer women equal pay, privileges and protection. The WAC was created in July 1943. By war’s end, over 18,000 WAAC and WAC women served over seas.

U.S. #4510

2011 84¢ Oveta Culp Hobby

Issue Date: April 15, 2011

City: Houston, TX

Printed By: Avery Dennison

Printing Method: Photogravure

Color: Multicolored

“Women who stepped up were measured as

citizens of the nation, not as women...

This was a people’s war, and everyone was in it.”

– Oveta Culp Hobby

Oveta Culp Hobby (1905-95) responded when called upon to serve her country. In the process, she created new opportunities for women, helped the Allies win World War II, and approved a drug that virtually eliminated polio in the United States.

During World War II, Hobby became the Director of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, created to remedy severe labor shortages caused by men serving in the war effort. Its members, who were the first women other than nurses to be in Army uniform, helped the U.S. meet the industrial demands needed to win the war. Although she “never did learn to salute properly or master the 30-inch stride,” Colonel Oveta Hobby became the first woman in the Army to receive the Distinguished Service Medal.

President Dwight Eisenhower named Hobby the first secretary of the new Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Hobby personally made the decision to approve Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine. She resigned her position in 1955 to care for her ailing husband. Oveta died in 1995, knowing she had helped save two generations of Americans from the paralyzing effects of polio.

Formation Of WAAC

Prior to and at the start of World War II, women were generally only allowed on the battlefield as nurses or as volunteers as communications specialists or dieticians. Though they served with the Army, they didn’t have any official status, so they had to pay for their own food and lodging and didn’t receive any disability benefits or pensions when they returned home.

Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers knew all about this situation and was determined to get women the same protection and benefits as men if they were to be called on again. In early 1941, she met with General George C. Marshall the Army’s Chief of Staff, and told him of her plans to introduce a bill to create a women’s corps that was separate from the Nurse Corps.

Over time, the idea of a women’s corps gained support. However, while Rogers wanted to create an organization that was part of the army with equal pay, pension, and disability benefits, the Army was uneasy about accepting women right into its ranks. The resulting bill was a compromise. It would provide food, uniforms, living quarters, pay, and medical care for up to 150,000 women. However, the women would receive less pay than men of the same rank and didn’t receive overseas pay, government life insurance, veteran’s medical coverage, or protection if they were captured by enemy troops. Rogers had to give up some of her goals in order to get the bill onto the floor.

Rogers first introduced the bill in May 1941, but it didn’t receive much attention. It wasn’t until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that the bill was more seriously considered. General Marshall spoke out actively in favor of the bill. America was entering a two-front war and needed all the help it could get. The bill faced serious opposition, especially from southern congressmen, who asked “Who will then do the cooking, the washing, the mending, the humble homey tasks to which every woman has devoted herself; who will nurture the children?”

After significant debate, the House and Senate passed Rogers’ bill, which President Franklin Roosevelt signed into law on May 15, 1942. He initially set the recruitment goal at 25,000. That was met by November, after which time it was increased to 150,000.

The same day the bill was approved, Oveta Culp Hobby was made director of the WAAC. Hobby had worked as a newspaper editor and worked on the Texas legislature before speaking out in favor of the WAAC. Her first priority was recruiting women to serve as clerical workers, teachers, stenographers, and telephone operators. Every woman she recruited would “free a man for combat.” As Hobby explained, “The gaps our women will fill are in those noncombatant jobs where women’s hands and women’s hearts fit naturally. WAACs will do the same type of work which women do in civilian life. They will bear the same relation to men of the Army that they bear to the men of the civilian organizations in which they work.”

The first batch of officer recruits were an average age of 25 years old, most of whom attended college and worked in an office or as a teacher. One in five enlisted because a male family member was serving and they wanted to help him get home faster.

After extensive training, the first WAAC units were put to work with Aircraft Warning Service units. By October, there were 27 WAAC companies at these stations up and down the eastern seaboard. Soon other WAACs were assigned to the Army Air Forces, Army Ground Forces, or Army Services Forces. As time went on, the WAACs duties expanded significantly. By the last year of the war, only about half of the WAACs were performing traditional jobs. Other tasks included weather observers, cryptographers, repairs, parachute riggers, photograph analysts, control tower operations, electricians, and radio operators, among many other things.

As American military planners began looking toward another front in Europe, they realized a need for more manpower. Out of this need, talks began of creating the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), which would be a part of the Army, and not just serving with it. The WAC would also offer women equal pay, privileges and protection. The WAC was created in July 1943. By war’s end, over 18,000 WAAC and WAC women served over seas.