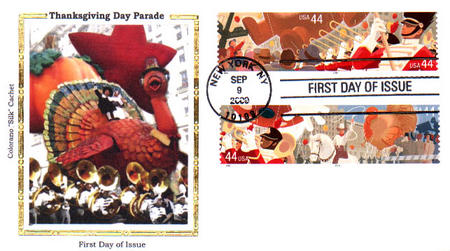

# 4417-20 PB - 2009 44c Thanksgiving Day Parade

Thanksgiving Day Parade

Issue Date: September 9, 2009

City: New York, NY

New York City’s Thanksgiving Day Parade is the “longest-running show on Broadway.” Alongside turkey dinner and pumpkin pie, it is one of the holiday’s best-known traditions.

An idea that began in 1924 with a group of Macy’s department store employees has grown into an American custom. Today, more than 3.5 million live spectators and 50 million television viewers are entertained by the pomp and pageantry that is the Thanksgiving Day Parade.

Every year, the best high school and college bands in the country march down Broadway on Thanksgiving morning. The heartbeat of the parade, marching bands get the crowd moving to their rhythmic beats.

Giant balloons are also crowd pleasers. The balloons first appeared in the Thanksgiving Day Parade in 1927, replacing the live zoo animals that frightened some children. Larger than life and lighter than air, these soaring giants enchant children of all ages.

The grand finale of every New York City Thanksgiving Day Parade is the float carrying Santa Claus. His arrival signals to everyone that the holidays have arrived. As his reindeer lead the sleigh into Herald Square, they usher in the transition to the Christmas season.

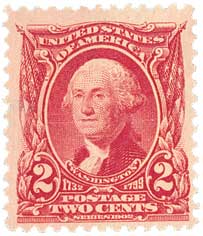

Washington & Lincoln’s Thanksgiving Celebrations

On November 26, 1789, the nation celebrated Thanksgiving for the first time under a presidential proclamation. Decades later, President Lincoln issued a similar proclamation that made the holiday permanent.

Though colonists had held harvest celebrations of thanks since the 1600s, it wasn’t an official holiday celebrated everywhere at the same time. Rather, it was celebrated in different places, at different times, and for different reasons.

That changed in 1789. On September 25, Elias Boudinot presented a resolution to the House of Representatives asking that President Washington “recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer… [for] the many signal favors of Almighty God.”

Congress approved the resolution and appointed a committee to approach Washington. Washington agreed and issued his proclamation on October 3. In it, he asked all Americans to observe November 26 as a day to give thanks to God for their victory in the Revolution as well as their establishment of a Constitution and government. He then gave it to the governors of each state and asked them to publish it for all to see. (You can read Washington’s proclamation here.)

Washington’s proclamation was then printed in newspapers around the country, leading to public celebrations of Thanksgiving on November 26. For his part, President Washington attended services at St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City and donated beer and food to those in debtors’ prisons.

In the years that followed, Presidents John Adams and James Madison issued similar proclamations, but none were permanent. In 1817, New York officially established an annual Thanksgiving holiday. Other northern states followed suit, though they weren’t all on the same day. Some presidents, such as Thomas Jefferson, opposed the proclamations. He believed it was contradictory to the nation’s beliefs in the separation of church and state.

Sarah Josepha Hale (famous for the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb”) began a rigorous campaign in 1827 to make Thanksgiving a national holiday. She published articles and wrote letters to countless politicians, to no avail. Finally, in 1863, at the height of the Civil War, President Lincoln received one of her letters and was inspired.

On October 3, Lincoln issued his own proclamation, establishing the last Thursday of November as a day of Thanksgiving. In particular, to pray for those who lost loved ones in the war and to “heal the wounds of the nation.” (You can read Lincoln’s proclamation here.) The first Thanksgiving celebrated under Lincoln’s proclamation was that year on November 26.

Thanksgiving continued to be celebrated on the last Thursday of November until 1939, when President Franklin Roosevelt moved it up a week to increase retail sales during the Great Depression. Americans were outraged and dubbed it “Franksgiving.” Two years later, he reversed his policy and signed a bill making Thanksgiving the fourth Thursday of November, as it has remained ever since.

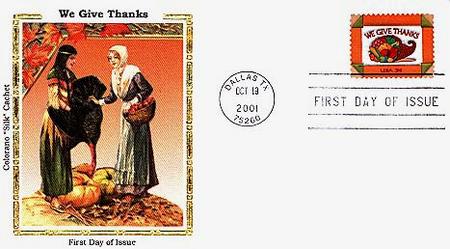

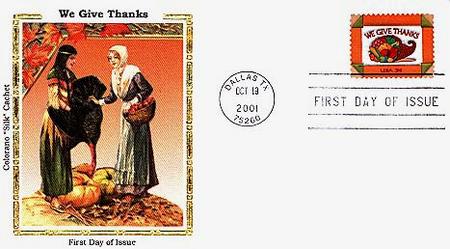

Thanksgiving Day Parade

Issue Date: September 9, 2009

City: New York, NY

New York City’s Thanksgiving Day Parade is the “longest-running show on Broadway.” Alongside turkey dinner and pumpkin pie, it is one of the holiday’s best-known traditions.

An idea that began in 1924 with a group of Macy’s department store employees has grown into an American custom. Today, more than 3.5 million live spectators and 50 million television viewers are entertained by the pomp and pageantry that is the Thanksgiving Day Parade.

Every year, the best high school and college bands in the country march down Broadway on Thanksgiving morning. The heartbeat of the parade, marching bands get the crowd moving to their rhythmic beats.

Giant balloons are also crowd pleasers. The balloons first appeared in the Thanksgiving Day Parade in 1927, replacing the live zoo animals that frightened some children. Larger than life and lighter than air, these soaring giants enchant children of all ages.

The grand finale of every New York City Thanksgiving Day Parade is the float carrying Santa Claus. His arrival signals to everyone that the holidays have arrived. As his reindeer lead the sleigh into Herald Square, they usher in the transition to the Christmas season.

Washington & Lincoln’s Thanksgiving Celebrations

On November 26, 1789, the nation celebrated Thanksgiving for the first time under a presidential proclamation. Decades later, President Lincoln issued a similar proclamation that made the holiday permanent.

Though colonists had held harvest celebrations of thanks since the 1600s, it wasn’t an official holiday celebrated everywhere at the same time. Rather, it was celebrated in different places, at different times, and for different reasons.

That changed in 1789. On September 25, Elias Boudinot presented a resolution to the House of Representatives asking that President Washington “recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer… [for] the many signal favors of Almighty God.”

Congress approved the resolution and appointed a committee to approach Washington. Washington agreed and issued his proclamation on October 3. In it, he asked all Americans to observe November 26 as a day to give thanks to God for their victory in the Revolution as well as their establishment of a Constitution and government. He then gave it to the governors of each state and asked them to publish it for all to see. (You can read Washington’s proclamation here.)

Washington’s proclamation was then printed in newspapers around the country, leading to public celebrations of Thanksgiving on November 26. For his part, President Washington attended services at St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City and donated beer and food to those in debtors’ prisons.

In the years that followed, Presidents John Adams and James Madison issued similar proclamations, but none were permanent. In 1817, New York officially established an annual Thanksgiving holiday. Other northern states followed suit, though they weren’t all on the same day. Some presidents, such as Thomas Jefferson, opposed the proclamations. He believed it was contradictory to the nation’s beliefs in the separation of church and state.

Sarah Josepha Hale (famous for the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb”) began a rigorous campaign in 1827 to make Thanksgiving a national holiday. She published articles and wrote letters to countless politicians, to no avail. Finally, in 1863, at the height of the Civil War, President Lincoln received one of her letters and was inspired.

On October 3, Lincoln issued his own proclamation, establishing the last Thursday of November as a day of Thanksgiving. In particular, to pray for those who lost loved ones in the war and to “heal the wounds of the nation.” (You can read Lincoln’s proclamation here.) The first Thanksgiving celebrated under Lincoln’s proclamation was that year on November 26.

Thanksgiving continued to be celebrated on the last Thursday of November until 1939, when President Franklin Roosevelt moved it up a week to increase retail sales during the Great Depression. Americans were outraged and dubbed it “Franksgiving.” Two years later, he reversed his policy and signed a bill making Thanksgiving the fourth Thursday of November, as it has remained ever since.