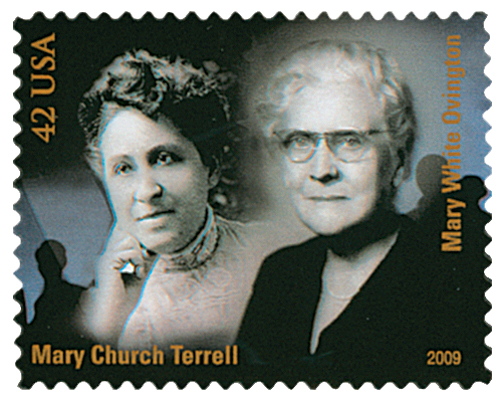

# 4384a FDC - 2009 42c Civil Rights Pioneers: Mary Church Terrell and Mary White Ovington

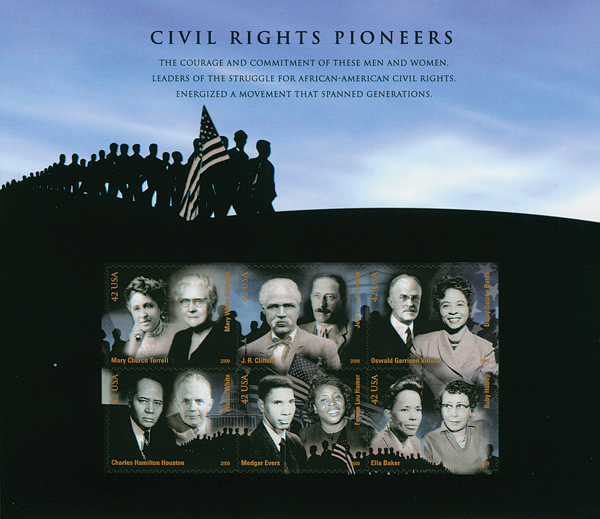

Civil Rights Pioneers

Mary Church Terrell and Mary White Ovington

City: New York, NY

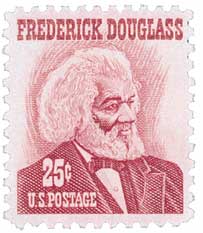

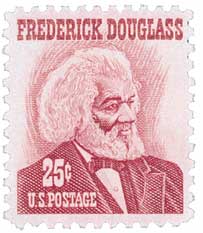

Mary White Ovington, suffragette and journalist, co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Called the “Mother of the new Emancipation,” her lifelong fight for equal rights was fueled by the oratory of Frederick Douglass.

Ovington was further inspired by an article about the violent race riots in Illinois. The outcome of her meeting with the author was a 1909 conference planned for the 100th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth. This important event led to the founding of the National Negro Committee, and the next year, the NAACP.

Ovington was involved in several successful Supreme Court appeals against discriminatory laws in the South.

Birth Of Mary Church Terrell

Terrell was born to entrepreneurial freed slaves – her father was the first African-American millionaire in the South and her mother was one of the first African-American women to run her own successful hair salon.

Terrell received her early education at the Antioch College Model School in Ohio because her mother didn’t think the schools in Memphis were good enough. She then went on to become one of the first African American women to attend Oberlin College, where she majored in Classics. During her time there, she was voted class poet, joined two literary societies, and worked as an editor of the school paper. She was then one of the first African American women to earn a bachelor’s degree in 1884, before going on to earn her master’s four years later.

After graduating, Terrell began teaching at Wilberforce College in Ohio. She then moved to Washington, DC, where she taught Latin at the M. Street School. Terrell also spent two years in Europe studying French, German, and Italian.

Terrell became interested in activism while she was in college, becoming particularly interested in Susan B. Anthony’s work for women’s rights. She had also met Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington, who were both friends of her father. Over the course of her career, she worked on several civil rights campaigns with Douglass. And when she considered abandoning activism for a private life, he convinced her that she was too important to the cause.

After a friend’s lynching, Terrell sought President Benjamin Harrison’s public support against racial violence. Failing that, she adopted the pen name Euphemia Kirk and often wrote about the civil rights of both blacks and women for newspapers around the country. In 1892, Terrell was elected the first female president of the Bethel Literary and Historical Society in Washington, DC. And in 1896 she became the first president of the National Association of Colored Women, which created nurseries and kindergartens. That same year she also founded the National Association of College Women. Terrell’s work ultimately led to her appointment to the District of Columbia Board of Education in 1895, a post she held until 1906. She was the first African American woman in that position. In 1909, Terrell was one of two African American women to participate in the organizational meeting of the NAACP.

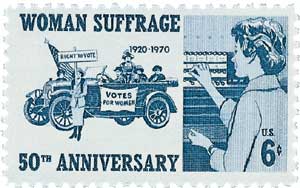

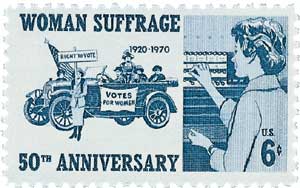

During World War I, Terrell worked with the War Camp Community Service. As the war ended, she worked with the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage and also attended the International Peace Conference. She was very active in the women’s suffrage movement, pushing for the passage of the 19thAmendment that gave them the right to vote.

In 1949, Terrell and some of her colleagues were denied service at a local restaurant. They quickly filed a lawsuit and over the next three years, Terrell staged boycotts, sit-ins, and demonstrations against other segregated restaurants. Then in June 1953, the court ruled these segregated restaurants in Washington, DC were unconstitutional.

Civil Rights Pioneers

Mary Church Terrell and Mary White Ovington

City: New York, NY

Mary White Ovington, suffragette and journalist, co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Called the “Mother of the new Emancipation,” her lifelong fight for equal rights was fueled by the oratory of Frederick Douglass.

Ovington was further inspired by an article about the violent race riots in Illinois. The outcome of her meeting with the author was a 1909 conference planned for the 100th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth. This important event led to the founding of the National Negro Committee, and the next year, the NAACP.

Ovington was involved in several successful Supreme Court appeals against discriminatory laws in the South.

Birth Of Mary Church Terrell

Terrell was born to entrepreneurial freed slaves – her father was the first African-American millionaire in the South and her mother was one of the first African-American women to run her own successful hair salon.

Terrell received her early education at the Antioch College Model School in Ohio because her mother didn’t think the schools in Memphis were good enough. She then went on to become one of the first African American women to attend Oberlin College, where she majored in Classics. During her time there, she was voted class poet, joined two literary societies, and worked as an editor of the school paper. She was then one of the first African American women to earn a bachelor’s degree in 1884, before going on to earn her master’s four years later.

After graduating, Terrell began teaching at Wilberforce College in Ohio. She then moved to Washington, DC, where she taught Latin at the M. Street School. Terrell also spent two years in Europe studying French, German, and Italian.

Terrell became interested in activism while she was in college, becoming particularly interested in Susan B. Anthony’s work for women’s rights. She had also met Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington, who were both friends of her father. Over the course of her career, she worked on several civil rights campaigns with Douglass. And when she considered abandoning activism for a private life, he convinced her that she was too important to the cause.

After a friend’s lynching, Terrell sought President Benjamin Harrison’s public support against racial violence. Failing that, she adopted the pen name Euphemia Kirk and often wrote about the civil rights of both blacks and women for newspapers around the country. In 1892, Terrell was elected the first female president of the Bethel Literary and Historical Society in Washington, DC. And in 1896 she became the first president of the National Association of Colored Women, which created nurseries and kindergartens. That same year she also founded the National Association of College Women. Terrell’s work ultimately led to her appointment to the District of Columbia Board of Education in 1895, a post she held until 1906. She was the first African American woman in that position. In 1909, Terrell was one of two African American women to participate in the organizational meeting of the NAACP.

During World War I, Terrell worked with the War Camp Community Service. As the war ended, she worked with the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage and also attended the International Peace Conference. She was very active in the women’s suffrage movement, pushing for the passage of the 19thAmendment that gave them the right to vote.

In 1949, Terrell and some of her colleagues were denied service at a local restaurant. They quickly filed a lawsuit and over the next three years, Terrell staged boycotts, sit-ins, and demonstrations against other segregated restaurants. Then in June 1953, the court ruled these segregated restaurants in Washington, DC were unconstitutional.