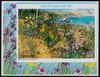

# 4352 - 2008 42c Nature of American: Great Lakes Dunes

U.S. #4352

Great Lakes Dunes

Nature of America Series

Issue Date: October 2, 2008

City: Empire, MI

Vesper sparrows are known for their evening songs. The birds were named after the Roman goddess Venus, the “Evening Star.” Often, male sparrows find a high perch, such as a shrub or fencepost, to declare their ownership of a nesting territory. The sparrow’s song is made up of two to four long, clear notes, followed by a series of slurs and trills.

These birds adapt easily to changes in habitat and are noted for being the first creatures to arrive in reclaimed mine sites and forests. Mother sparrows are very protective of their chicks, often causing diversions to keep them safe. When their chicks or nest are in danger, the mothers will fly away slowly or fake an injury to distract predators and allow their chicks to find safety.

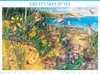

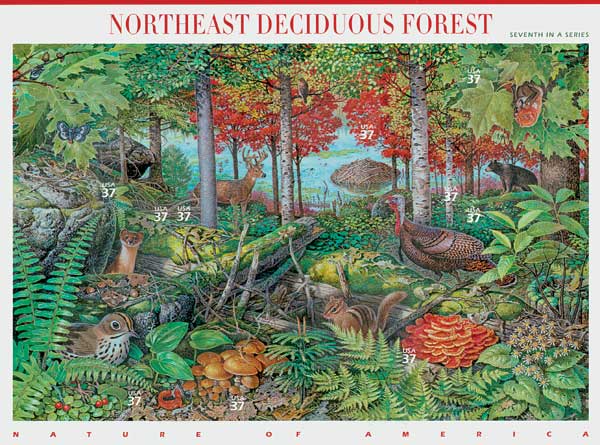

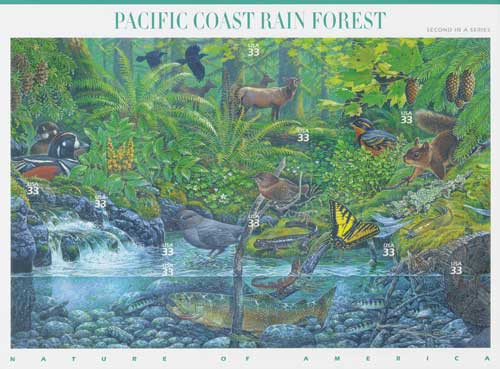

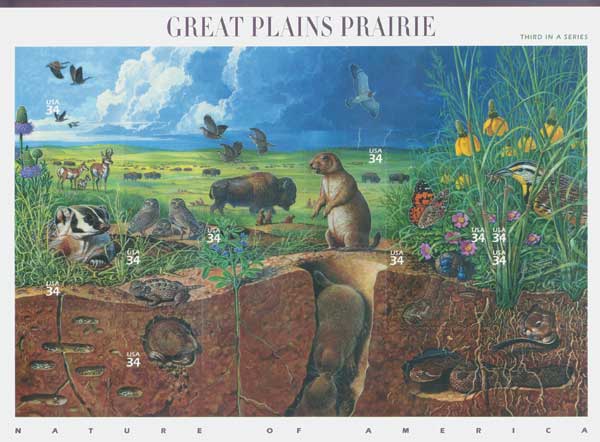

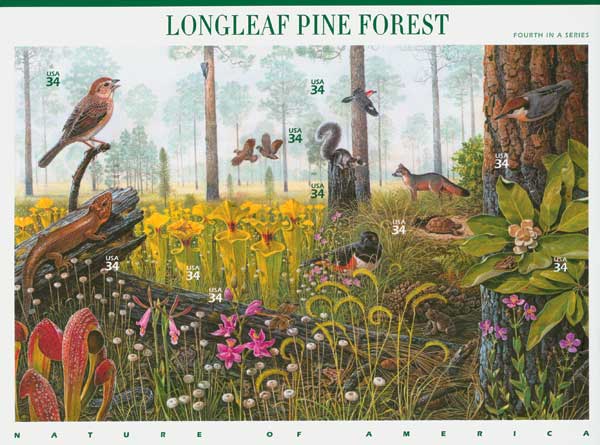

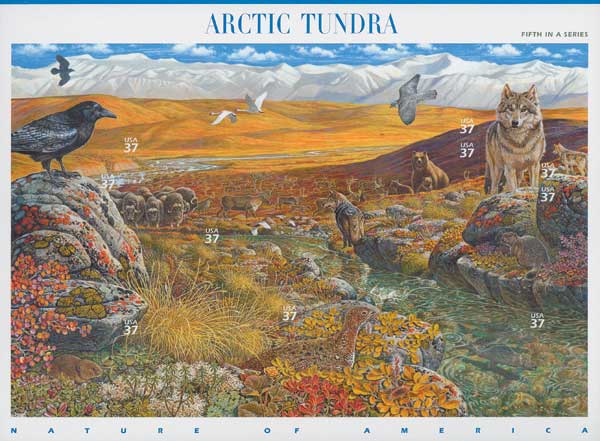

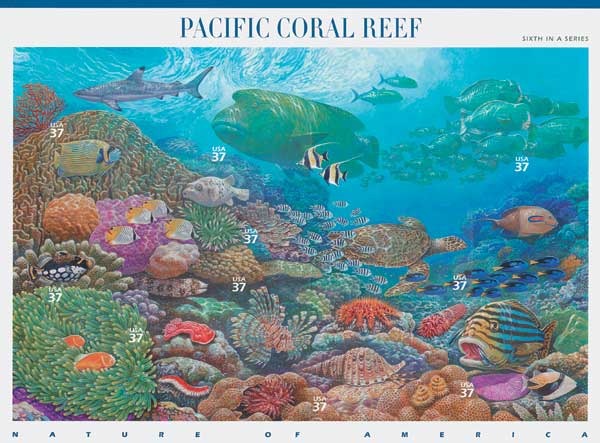

U.S.P.S. Introduces Nature Of America Series

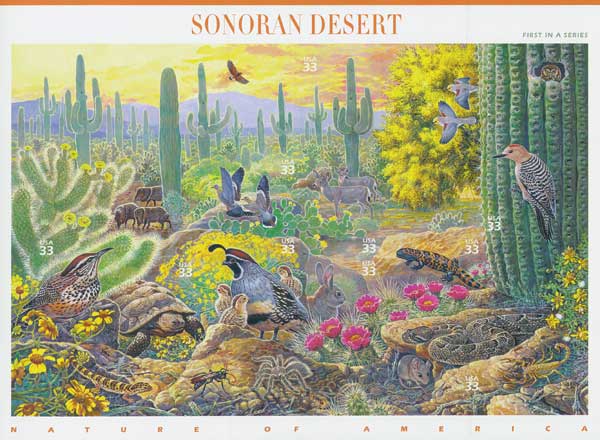

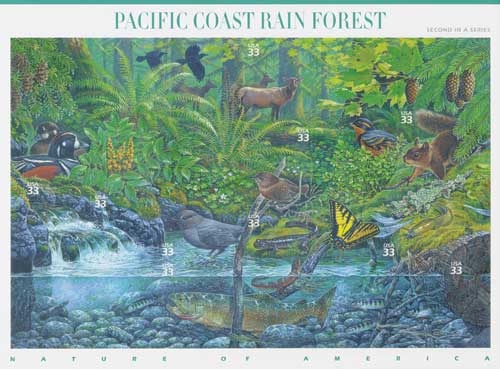

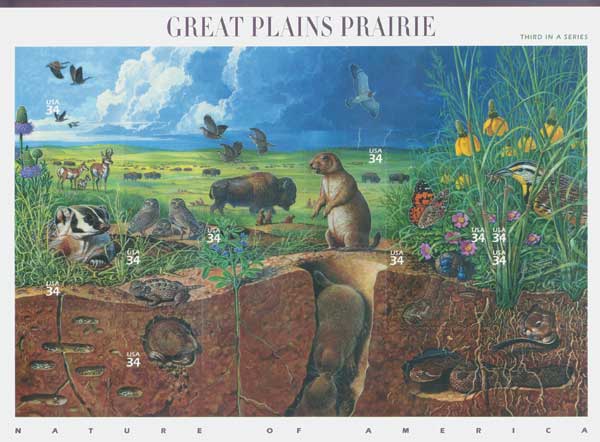

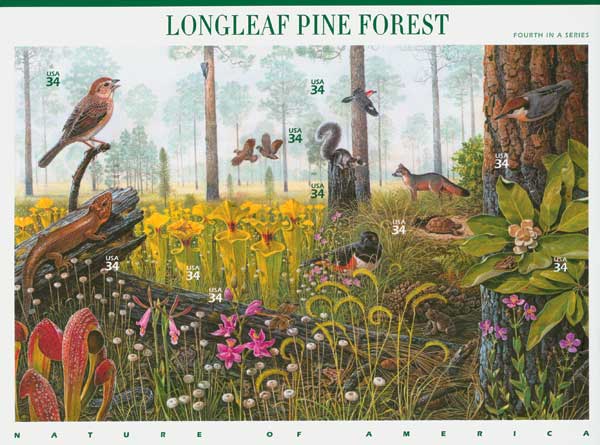

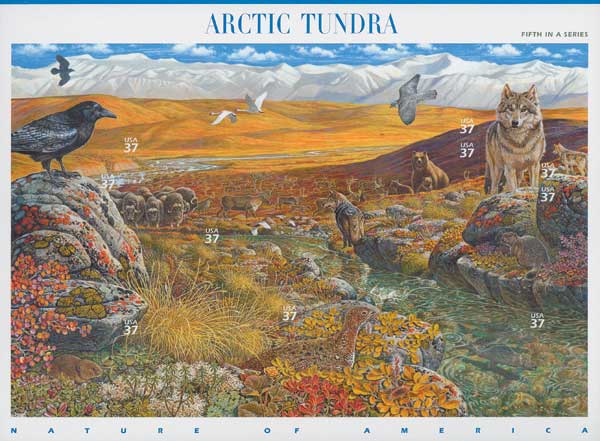

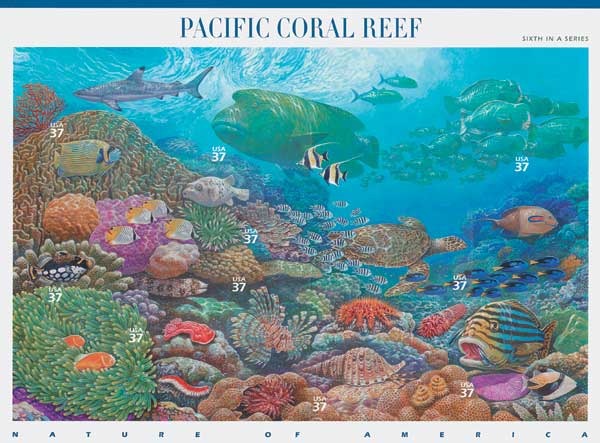

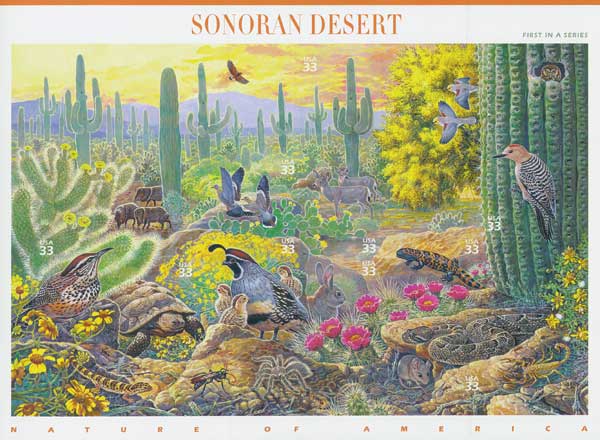

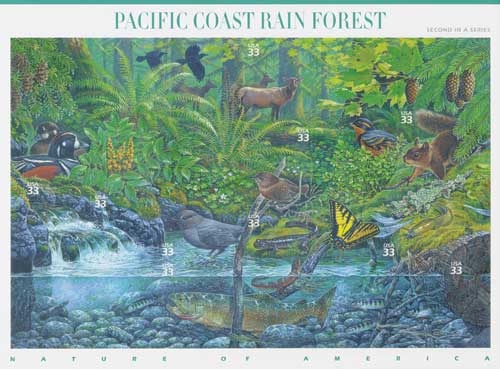

On April 6, 1999, the U.S.P.S. issued the first stamp sheet in its 12-year Nature of America series.

Before settling on Nature of America, the U.S.P.S. discussed issuing a set of four American desert stamps, based on the popularity of the 1981 Desert Plants stamps. Over time, the concept for the stamps evolved into a set of six stamp sheets depicting six ecosystems found in America.

U.S.P.S. art director Howard Paine suggested the stamps all use artwork by John D. Dawson, who’d previously worked on the 1988 American Cats, 1990 Idaho Statehood, and 1998 Flowering Trees stamps. They believed it was important for the same artist to create the artwork for all the stamp sheets, so they’d look like a set.

Some of the design inspiration for these stamps came from the 1997 World of Dinosaurs issue. The Dinosaurs sheet featured a panoramic view with perforations punched into the ungummed sheet. While they liked the idea of picturing a larger scene, the team didn’t want to use the punched perforations, because it would distract from the design. Instead they opted for the self-adhesive format with serpentine die cutting for each stamp. These stamps would be the first U.S. self-adhesive issues designed as one large scene.

The result is a stunning sheet with 10 stamps, each including one or more species found in that region. Outside of each stamp there are additional plants and animals, so the sheets actually picture 20 to 30 different species. Plus, the back of each sheet includes an outline of the artwork and identification for all the plants and animals. Click here to see the back of the Sonoran Desert sheet.

While the scene pictured on each sheet came from Dawson’s imagination, it was thoroughly researched. He used photos as references for each creature and worked closely with scientists to ensure he pictured all the species interacting in a realistic way on every sheet.

The first sheet in the Nature of America series was issued on April 6, 1999. Picturing the Sonoran Desert, its first day ceremony was held at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum in Tucson, Arizona. According to a U.S.P.S. representative at the ceremony, “these stamps will help promote a greater appreciation for the diversity and beauty of our desert lands, and serve as a nature lesson for the enjoyment of young and old alike.” Among the ceremony’s participants were some of the animals pictured on the new stamps.

The Sonoran Desert and the other five planned Nature of America sheets proved to be so popular, the series was extended to include six more ecosystems. One sheet was issued each year from 1999 until 2010.

Click any of the images above or below to learn more about the stamps and regions they picture. And click here to get the complete set of 12 Nature of America sheets.

When unthreatened, vesper sparrows commonly travel on the ground, despite being good flyers. If approached cautiously, these small birds won’t fly away, but will rather run along the path. They will normally run ahead of observers, occasionally stopping to look around. When courting, the male sparrows can be seen running along the ground with wings raised and tail spread. They will occasionally take short flights and sing before returning to the ground and running again.

North American red foxes are known for their superior stealth and hunting skills. Red foxes, part of the canid family (the same as dogs and wolves) have remarkable eyesight. Their vison is often compared to that of felines, earning them the nickname of “the cat-like canid.”

These foxes also have exceptional low-frequency hearing. They can easily hear small animals digging underground and will frantically dig through snow and dirt to find their prey. These sly predators use a number of tactics to catch their food. When hunting rabbits, they sneak up close to the small animal and then sprint quickly after it, sometimes reaching speeds up to 45 miles an hour. The fox also has a distinct style when hunting mice. Once the fox hears a mouse, it stands silent and motionless, and then suddenly leaps high into the air, landing on the mouse and pinning it to the ground. Red foxes learn to hunt while still young. When they are just a few weeks old, their parents bring home small, live animals for them to practice hunting and killing.

These foxes can also communicate through facial expressions, scent markings, and sounds. There are 28 recorded red fox vocalizations and some more experienced listeners can even identify their individual voices.

Piping plovers, small, sparrow-sized birds, are recognizable by their sandy color. This coloring benefits as well as hurts these birds. Their coloring is dangerous to them, as humans often step on the birds or drive over them, since they are nearly invisible in the sand.

When hunting for insects and other food they stand still, blending in with the sand before striking. They often use the run-stop-scan technique by leaning toward the ground and pecking at the surface. Their “foot-tremble” method surprises their prey into movement so the plover can attack unexpectedly. These birds normally live, hunt, and migrate in small numbers.

Piping plovers are so named because of their unique call. When standing or flying, the bird’s call is a soft whistle. Their more frequently heard alarm call is a soft “pee-werp,” with the latter half of the call at a lower pitch. When males are attempting to court females, they repeat a high-pitched, sometimes drawn-out song up to 40 or more times per flight. The flights are usually made in the shape of a figure eight. When threatened, plovers are known for their aggressive behavior. Often, plovers bite, peck, or otherwise attack intruders in their territory.

Eastern hog-nosed snakes are recognizable for their pig-like “nose.” They use this snout to dig in the dirt and sand to find toads. Often, when toads are captured by the snakes, they inflate themselves to prevent being eaten. However, eastern hog-nosed snakes have wide mouths, flexible jaws, and curved teeth.

They also have larger teeth in the back of their mouths they use to deflate toads. Additionally, these snakes create a special hormone that allows them to eat toads without even suffering from their toxic secretions. They have special salivary glands that produce a toxic substance to subdue amphibians, but is harmless to humans and other animals.

When threatened, these snakes raise their heads and flatten their necks (similar to cobras). The two large blotches on the back of their necks look like eyes and sometimes scare away predators. They then hiss and lunge at their threat, but never bite. Next, the snakes coil and uncoil their tails and secrete a foul-smelling odor that they writhe around in. If an intruder remains, the snakes convulse, dragging themselves through the dirt, then lying on their backs with their tongues out, playing dead. If turned over, they quickly flip themselves on their backs again.

Common mergansers are the largest of the three merganser species in North America. They have serrated bills that they use to catch slippery fish, which has earned them the nickname of “sawbills.”

These mergansers often float along bodies of water in search of food. Once they spot a fish, the mergansers dive under water, swimming until they catch their prey. Excellent swimmers, these birds will dive into rushing waters and under ice through water that is almost entirely frozen over in search of food. Mergansers are such good hunters that other birds, including gulls and eagles, often wait for them to surface to steal their catch. They usually attempt to swallow their fish whole, causing them to wait for the fish’s head to digest before they can swallow the rest of its body.

If mergansers are disturbed while hunting, they will fly away. Because these birds’ wings are small relative to their body size, they usually skitter along the surface of the water for a brief period before taking flight. Although they may take a while to get in to the air, once they are in flight, common mergansers are exceptionally fast flyers. Male mergansers’ courtship rituals include chasing each other on the water, in the air, and underwater.

Spotted sandpipers have a characteristic walk that intrigues and baffles scientists. When walking, hunting, or nervous, these birds often move with an up-and-down bobbing motion. This has earned these birds the nickname of “teeter-tail.” Chicks adopt this walk nearly as soon as they hatch. Extensive study of spotted sandpipers has yet to explain why they move this way.

Also of great interest to scientists is the sandpiper’s mating habits. The majority of these birds are polyandrous, meaning the females mate with more than one male. The females arrive at the nesting grounds about four days before the males, establishing their territory. As the males arrive, the females compete with each other over territories and males. These fights often include pecking at their opponent’s head and eyes while simultaneously trying to mount their back.

Each female then mates with a male and the pair builds a nest. In most cases, the female then leaves the male to incubate the eggs while she leaves to find and mate with another male. Female

U.S. #4352

Great Lakes Dunes

Nature of America Series

Issue Date: October 2, 2008

City: Empire, MI

Vesper sparrows are known for their evening songs. The birds were named after the Roman goddess Venus, the “Evening Star.” Often, male sparrows find a high perch, such as a shrub or fencepost, to declare their ownership of a nesting territory. The sparrow’s song is made up of two to four long, clear notes, followed by a series of slurs and trills.

These birds adapt easily to changes in habitat and are noted for being the first creatures to arrive in reclaimed mine sites and forests. Mother sparrows are very protective of their chicks, often causing diversions to keep them safe. When their chicks or nest are in danger, the mothers will fly away slowly or fake an injury to distract predators and allow their chicks to find safety.

U.S.P.S. Introduces Nature Of America Series

On April 6, 1999, the U.S.P.S. issued the first stamp sheet in its 12-year Nature of America series.

Before settling on Nature of America, the U.S.P.S. discussed issuing a set of four American desert stamps, based on the popularity of the 1981 Desert Plants stamps. Over time, the concept for the stamps evolved into a set of six stamp sheets depicting six ecosystems found in America.

U.S.P.S. art director Howard Paine suggested the stamps all use artwork by John D. Dawson, who’d previously worked on the 1988 American Cats, 1990 Idaho Statehood, and 1998 Flowering Trees stamps. They believed it was important for the same artist to create the artwork for all the stamp sheets, so they’d look like a set.

Some of the design inspiration for these stamps came from the 1997 World of Dinosaurs issue. The Dinosaurs sheet featured a panoramic view with perforations punched into the ungummed sheet. While they liked the idea of picturing a larger scene, the team didn’t want to use the punched perforations, because it would distract from the design. Instead they opted for the self-adhesive format with serpentine die cutting for each stamp. These stamps would be the first U.S. self-adhesive issues designed as one large scene.

The result is a stunning sheet with 10 stamps, each including one or more species found in that region. Outside of each stamp there are additional plants and animals, so the sheets actually picture 20 to 30 different species. Plus, the back of each sheet includes an outline of the artwork and identification for all the plants and animals. Click here to see the back of the Sonoran Desert sheet.

While the scene pictured on each sheet came from Dawson’s imagination, it was thoroughly researched. He used photos as references for each creature and worked closely with scientists to ensure he pictured all the species interacting in a realistic way on every sheet.

The first sheet in the Nature of America series was issued on April 6, 1999. Picturing the Sonoran Desert, its first day ceremony was held at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum in Tucson, Arizona. According to a U.S.P.S. representative at the ceremony, “these stamps will help promote a greater appreciation for the diversity and beauty of our desert lands, and serve as a nature lesson for the enjoyment of young and old alike.” Among the ceremony’s participants were some of the animals pictured on the new stamps.

The Sonoran Desert and the other five planned Nature of America sheets proved to be so popular, the series was extended to include six more ecosystems. One sheet was issued each year from 1999 until 2010.

Click any of the images above or below to learn more about the stamps and regions they picture. And click here to get the complete set of 12 Nature of America sheets.

When unthreatened, vesper sparrows commonly travel on the ground, despite being good flyers. If approached cautiously, these small birds won’t fly away, but will rather run along the path. They will normally run ahead of observers, occasionally stopping to look around. When courting, the male sparrows can be seen running along the ground with wings raised and tail spread. They will occasionally take short flights and sing before returning to the ground and running again.

North American red foxes are known for their superior stealth and hunting skills. Red foxes, part of the canid family (the same as dogs and wolves) have remarkable eyesight. Their vison is often compared to that of felines, earning them the nickname of “the cat-like canid.”

These foxes also have exceptional low-frequency hearing. They can easily hear small animals digging underground and will frantically dig through snow and dirt to find their prey. These sly predators use a number of tactics to catch their food. When hunting rabbits, they sneak up close to the small animal and then sprint quickly after it, sometimes reaching speeds up to 45 miles an hour. The fox also has a distinct style when hunting mice. Once the fox hears a mouse, it stands silent and motionless, and then suddenly leaps high into the air, landing on the mouse and pinning it to the ground. Red foxes learn to hunt while still young. When they are just a few weeks old, their parents bring home small, live animals for them to practice hunting and killing.

These foxes can also communicate through facial expressions, scent markings, and sounds. There are 28 recorded red fox vocalizations and some more experienced listeners can even identify their individual voices.

Piping plovers, small, sparrow-sized birds, are recognizable by their sandy color. This coloring benefits as well as hurts these birds. Their coloring is dangerous to them, as humans often step on the birds or drive over them, since they are nearly invisible in the sand.

When hunting for insects and other food they stand still, blending in with the sand before striking. They often use the run-stop-scan technique by leaning toward the ground and pecking at the surface. Their “foot-tremble” method surprises their prey into movement so the plover can attack unexpectedly. These birds normally live, hunt, and migrate in small numbers.

Piping plovers are so named because of their unique call. When standing or flying, the bird’s call is a soft whistle. Their more frequently heard alarm call is a soft “pee-werp,” with the latter half of the call at a lower pitch. When males are attempting to court females, they repeat a high-pitched, sometimes drawn-out song up to 40 or more times per flight. The flights are usually made in the shape of a figure eight. When threatened, plovers are known for their aggressive behavior. Often, plovers bite, peck, or otherwise attack intruders in their territory.

Eastern hog-nosed snakes are recognizable for their pig-like “nose.” They use this snout to dig in the dirt and sand to find toads. Often, when toads are captured by the snakes, they inflate themselves to prevent being eaten. However, eastern hog-nosed snakes have wide mouths, flexible jaws, and curved teeth.

They also have larger teeth in the back of their mouths they use to deflate toads. Additionally, these snakes create a special hormone that allows them to eat toads without even suffering from their toxic secretions. They have special salivary glands that produce a toxic substance to subdue amphibians, but is harmless to humans and other animals.

When threatened, these snakes raise their heads and flatten their necks (similar to cobras). The two large blotches on the back of their necks look like eyes and sometimes scare away predators. They then hiss and lunge at their threat, but never bite. Next, the snakes coil and uncoil their tails and secrete a foul-smelling odor that they writhe around in. If an intruder remains, the snakes convulse, dragging themselves through the dirt, then lying on their backs with their tongues out, playing dead. If turned over, they quickly flip themselves on their backs again.

Common mergansers are the largest of the three merganser species in North America. They have serrated bills that they use to catch slippery fish, which has earned them the nickname of “sawbills.”

These mergansers often float along bodies of water in search of food. Once they spot a fish, the mergansers dive under water, swimming until they catch their prey. Excellent swimmers, these birds will dive into rushing waters and under ice through water that is almost entirely frozen over in search of food. Mergansers are such good hunters that other birds, including gulls and eagles, often wait for them to surface to steal their catch. They usually attempt to swallow their fish whole, causing them to wait for the fish’s head to digest before they can swallow the rest of its body.

If mergansers are disturbed while hunting, they will fly away. Because these birds’ wings are small relative to their body size, they usually skitter along the surface of the water for a brief period before taking flight. Although they may take a while to get in to the air, once they are in flight, common mergansers are exceptionally fast flyers. Male mergansers’ courtship rituals include chasing each other on the water, in the air, and underwater.

Spotted sandpipers have a characteristic walk that intrigues and baffles scientists. When walking, hunting, or nervous, these birds often move with an up-and-down bobbing motion. This has earned these birds the nickname of “teeter-tail.” Chicks adopt this walk nearly as soon as they hatch. Extensive study of spotted sandpipers has yet to explain why they move this way.

Also of great interest to scientists is the sandpiper’s mating habits. The majority of these birds are polyandrous, meaning the females mate with more than one male. The females arrive at the nesting grounds about four days before the males, establishing their territory. As the males arrive, the females compete with each other over territories and males. These fights often include pecking at their opponent’s head and eyes while simultaneously trying to mount their back.

Each female then mates with a male and the pair builds a nest. In most cases, the female then leaves the male to incubate the eggs while she leaves to find and mate with another male. Female