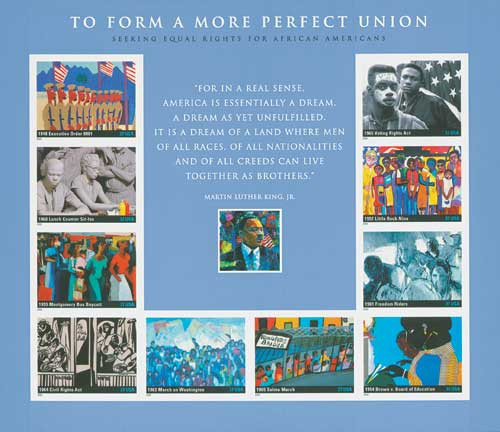

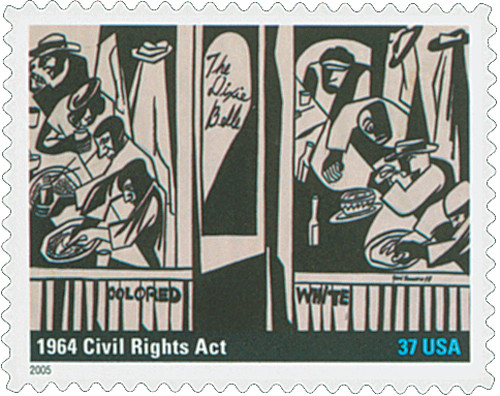

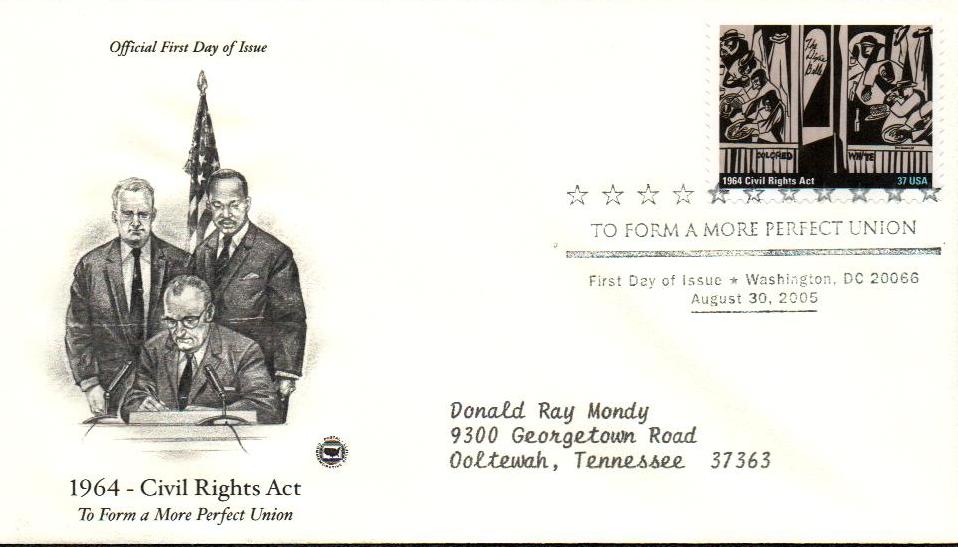

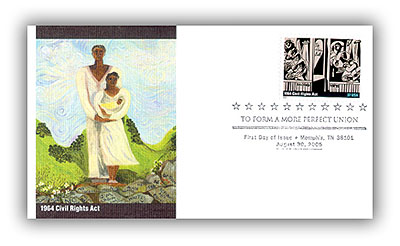

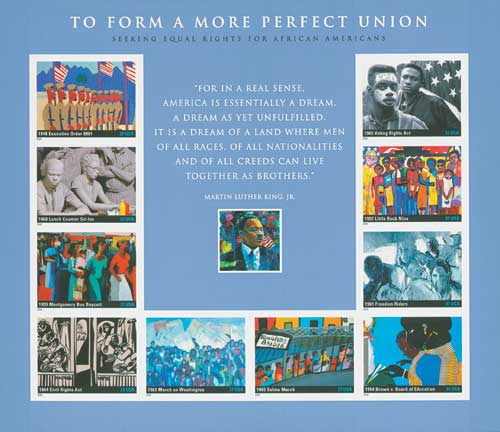

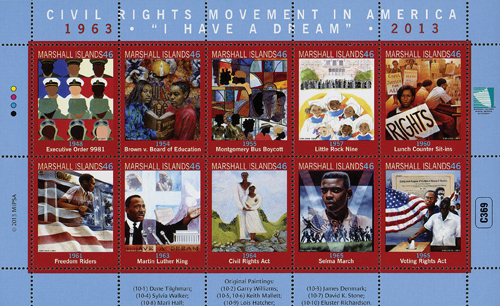

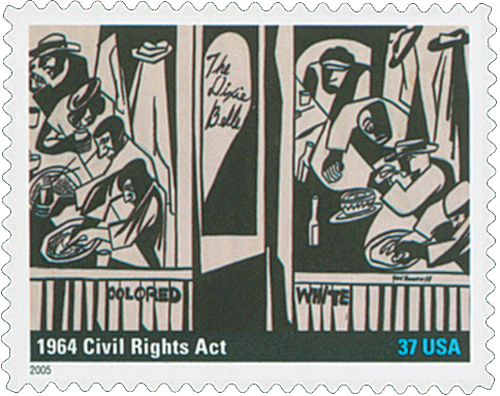

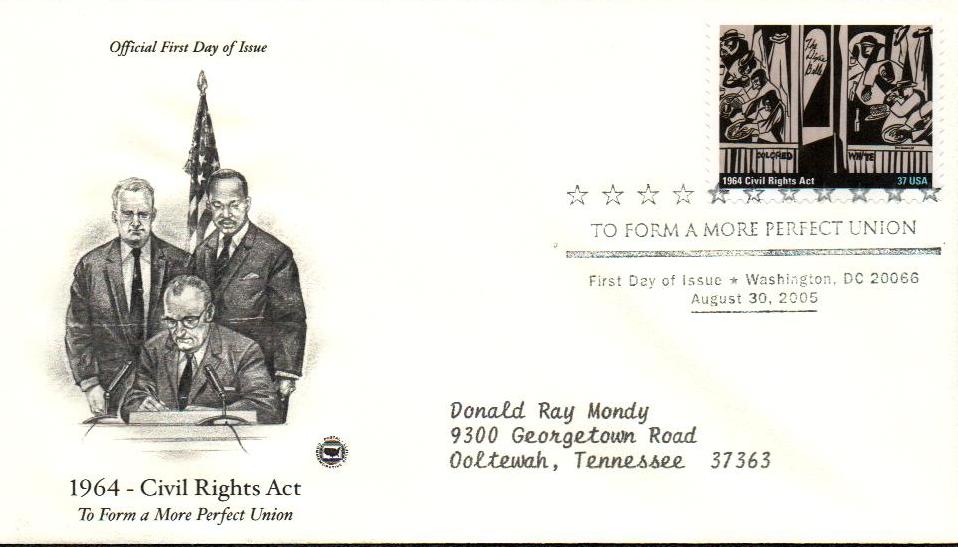

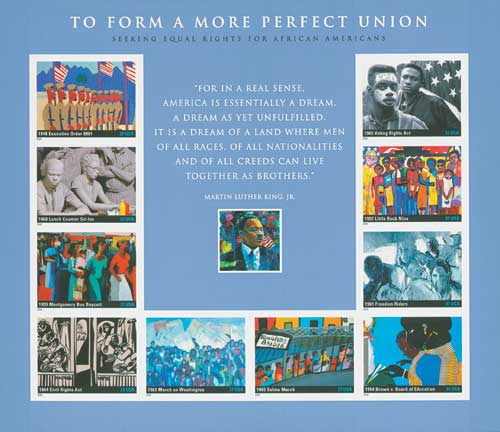

# 3937g FDC - 2005 37c To Form a More Perfect Union: Civil Rights Act

37¢ 1964 Civil Rights Act

To Form a More Perfect Union

City: Washington, DC

Printing Method: Lithographed

Color: Multicolored

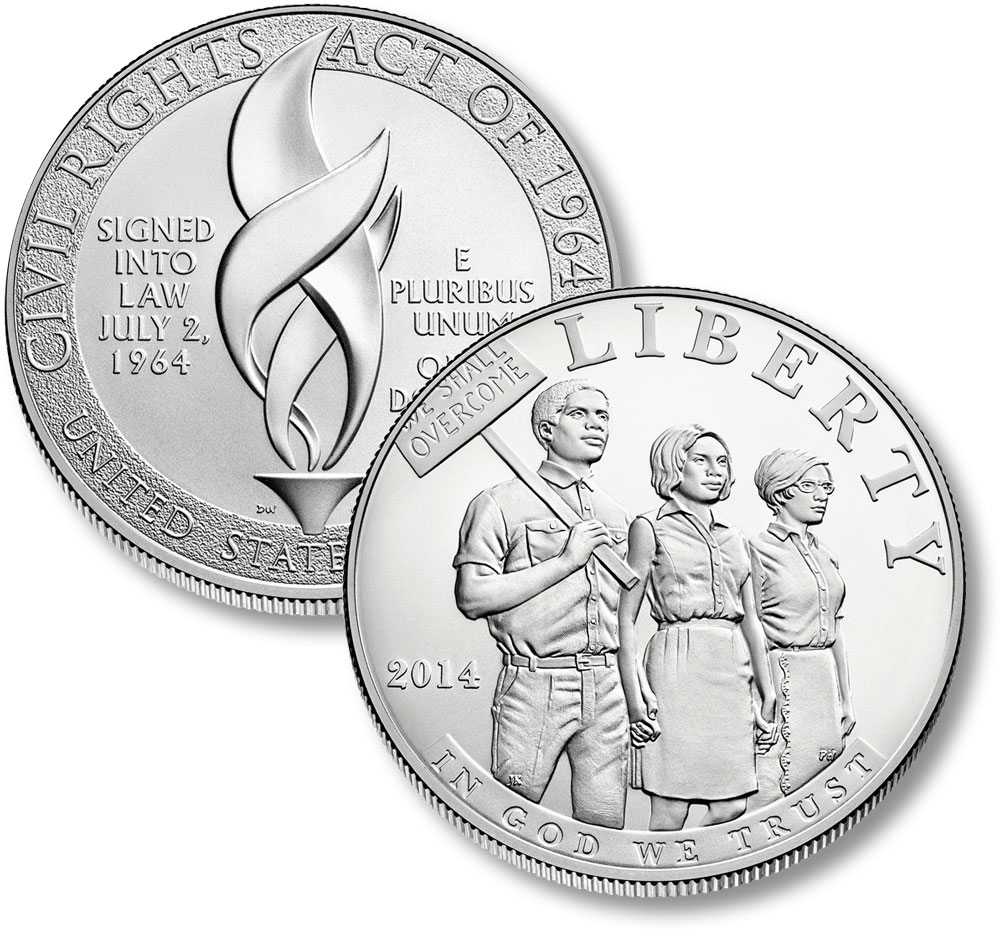

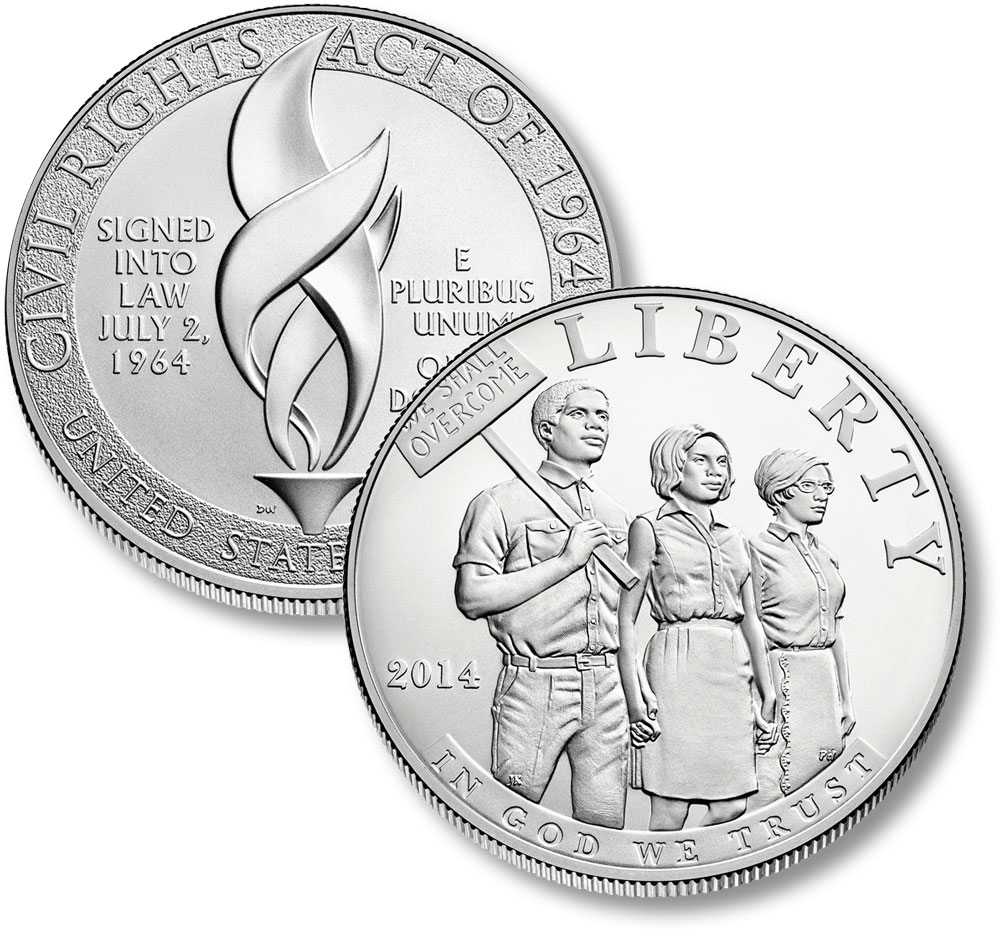

Civil Rights Act Of 1964

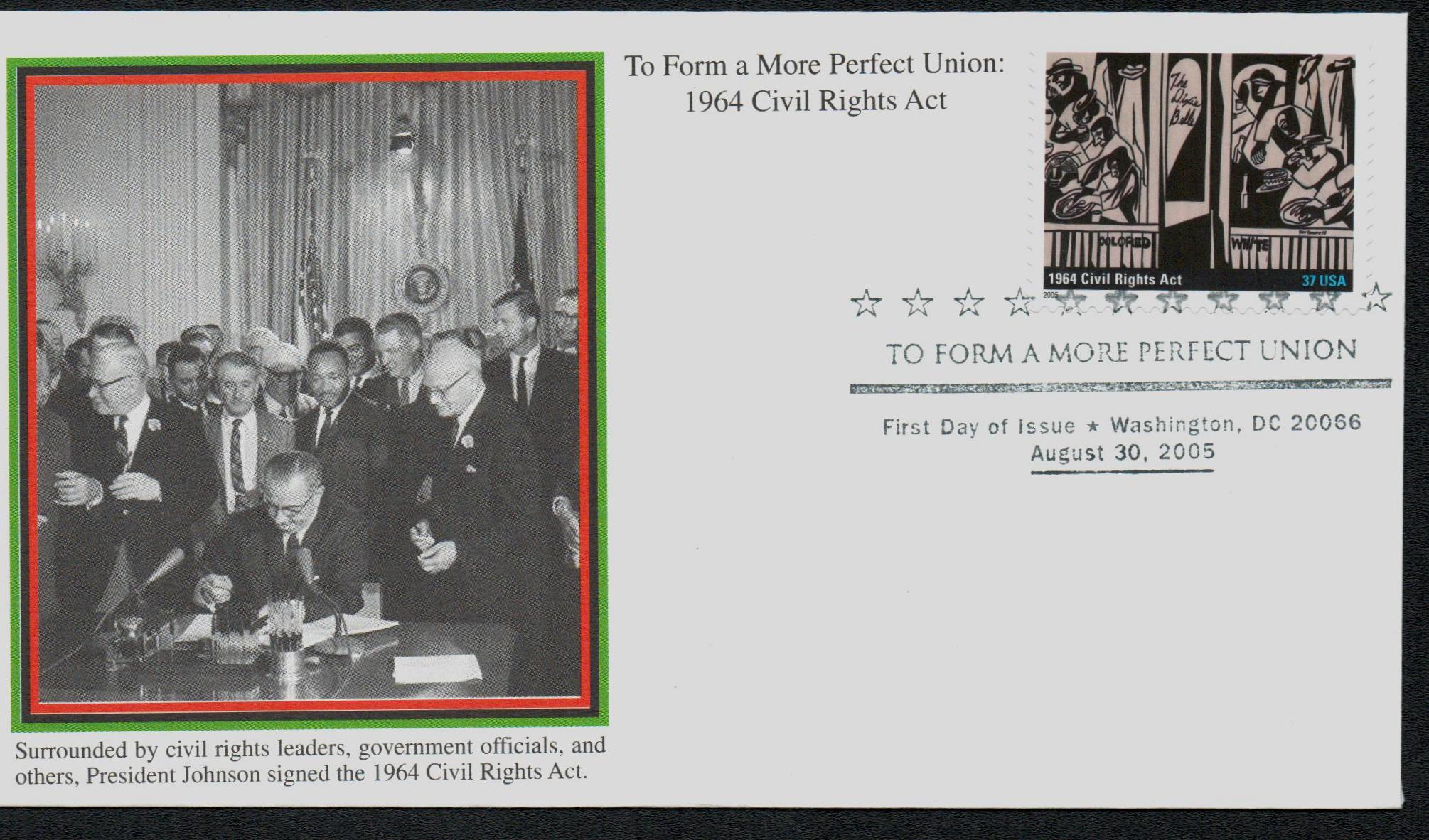

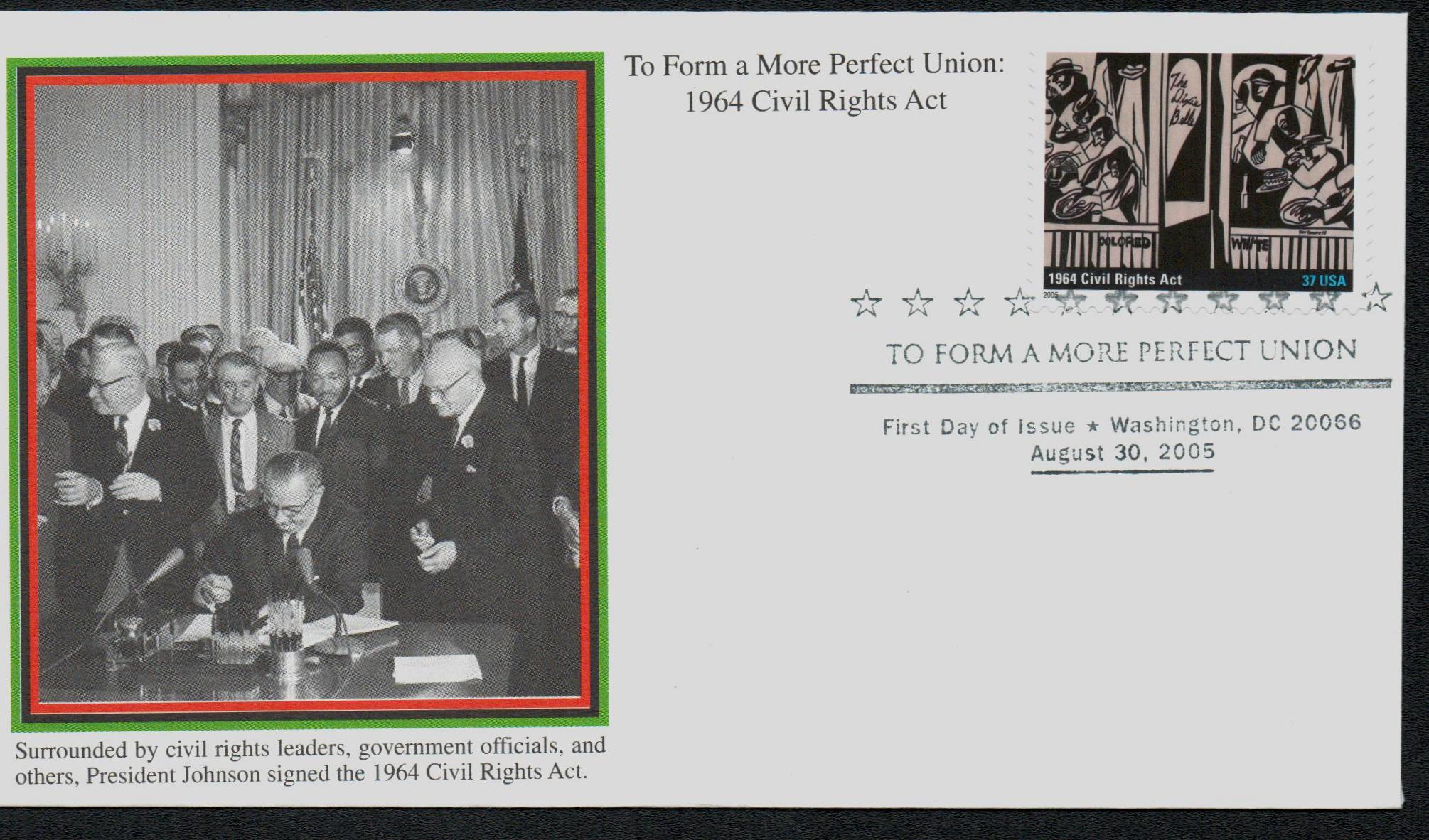

On July 2, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law, fulfilling a goal set by his predecessor, John F. Kennedy.

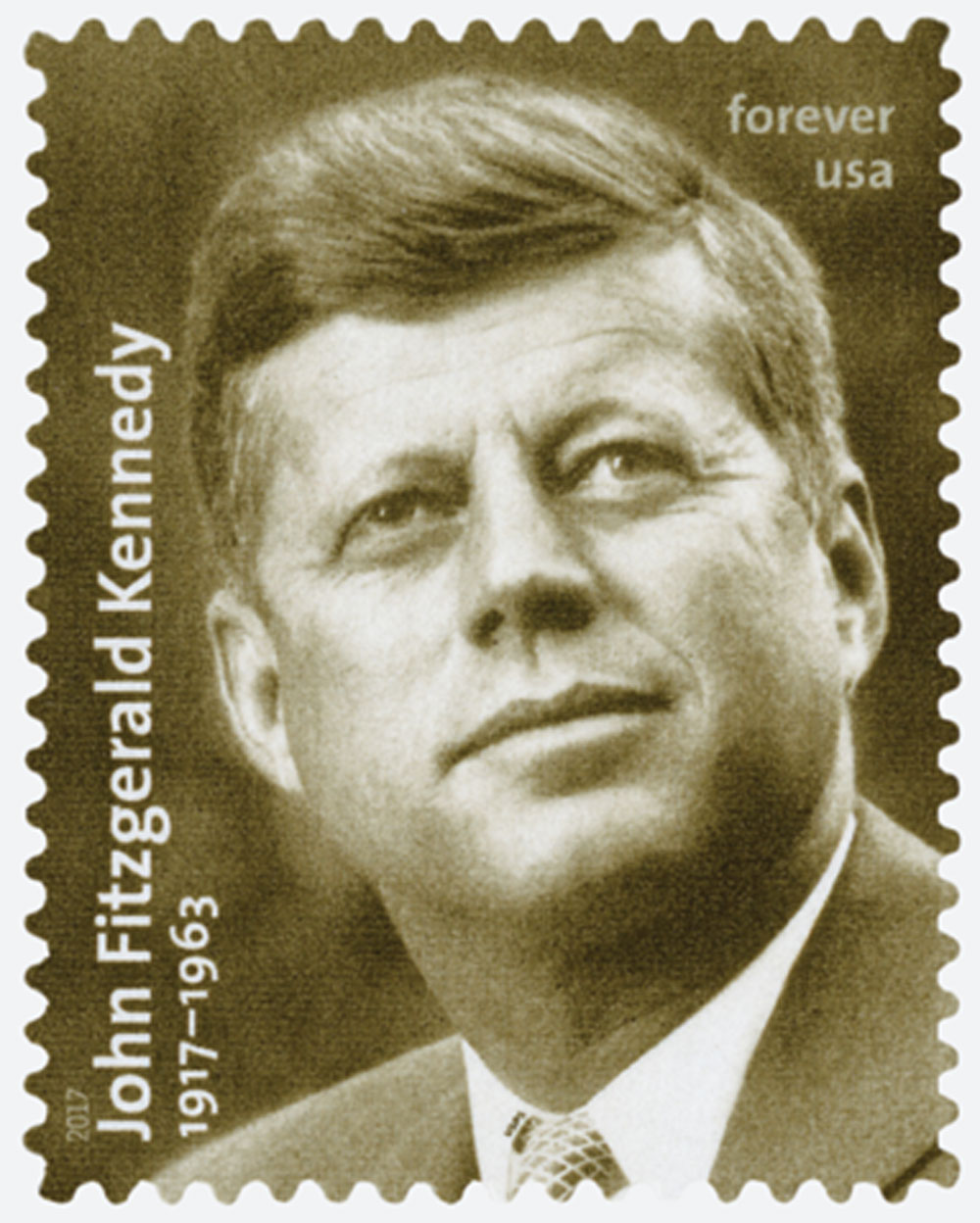

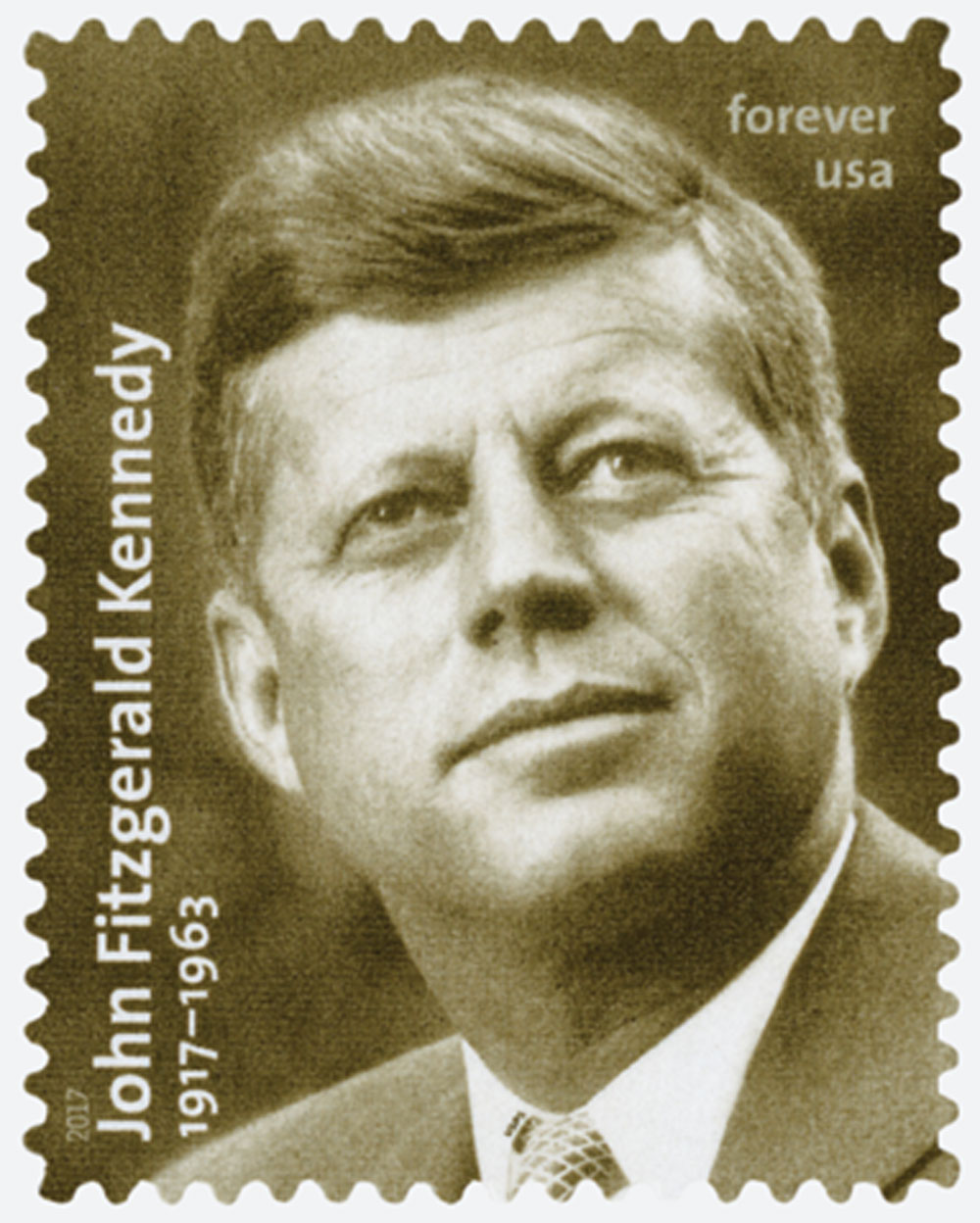

Early on in his career, John F. Kennedy did not speak out frequently concerning civil rights. However, his brief term in office came at a tumultuous time in US history, when the matter of civil rights became the defining issue of a generation.

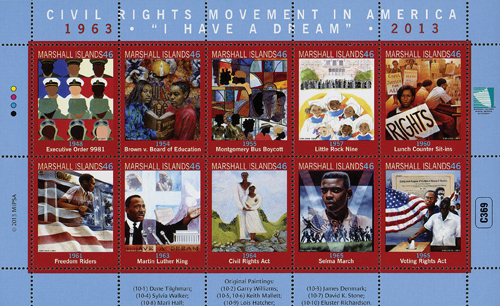

Mere months into his term, Kennedy faced his first major civil rights decision, concerning the 1961 Freedom Riders. That spring and summer hundreds of people rode southern interstate buses to oppose the practice of segregation, which had been outlawed on public buses. Some were arrested and attacked by local mobs. The violence and imprisonments brought the civil rights issue to national attention and showed that the federal government was not enforcing its own laws. In response, Kennedy sent federal marshals to guard the riders. Not wanting to lose support in the South though, he stressed that his decision was a legal issue, rather than a moral one.

The following year, Kennedy authorized federal troops to protect James Meredith, an African American attending the University of Mississippi. Though he insisted that it wouldn’t change his legislative plans. Then in 1963, as the movement became more violent and attracted international attention, Kennedy realized that stronger legislation would take the issue “out of the streets” and into the courts – away from international spectators. That February, he proposed a Civil Rights bill to Congress. He stated that it would have economic and diplomatic benefits, and argued that it should remove institutional racism because, “above all, it is wrong.”

Kennedy was further moved by the Birmingham campaign in May 1963, in which African American students staged nonviolent protests. Then on May 21, 1963, a federal judge ruled that the University of Alabama must allow two African American students to attend its summer courses. The governor of Alabama strongly opposed the order and insisted on making it a public display. On June 11, the students attempted to enter the school’s auditorium to register for classes, but the governor himself blocked the doorway. Kennedy then ordered federal troops to order him to step aside and allow the students to register.

In the wake of the nationally televised event, Kennedy decided it was time to address the nation on the civil rights issue. That night, at 8 p.m., Kennedy delivered his Civil Rights Address. He began by briefly talking about the events at the University of Alabama earlier in the day. Kennedy then stressed the importance that all Americans recognize civil rights as a moral cause that everyone should contribute to and that it was “as clear as the American Constitution.”

Kennedy’s address was well received by many people in the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King Jr. stated, “Can you believe that white man not only stepped up to the plate, he hit it over the fence!” Days later, on June 19, Kennedy sent his bill to Congress, saying its passage was “imperative.” Passage of the bill would be one of his major goals in the coming months.

Congress debated the bill and added a series of provisions to ban racial discrimination in employment, offer better protection to black voters, end segregation in all publicly owned buildings, and improve the anti-segregation clauses in regards to public facilities. Kennedy continued to push for the bill’s passage, but he wouldn’t live to see it, losing his life to an assassin’s bullet that November.

Upon taking office, Lyndon B. Johnson saw to it that Kennedy’s act be completed. Less than a week after becoming president, he addressed Congress, saying “No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy’s memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long.”

The House bill passed in February 1964, but Southern senators delayed the bill with a two-month filibuster. Hubert Humphrey, Everett Dirksen, and others submitted a new bill that they believed could get enough Republican swing votes to gain passage. Their new bill was accepted, passed, and signed into law by President Johnson on July 2, 1964.

Click here to read the full text of the act.

37¢ 1964 Civil Rights Act

To Form a More Perfect Union

City: Washington, DC

Printing Method: Lithographed

Color: Multicolored

Civil Rights Act Of 1964

On July 2, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law, fulfilling a goal set by his predecessor, John F. Kennedy.

Early on in his career, John F. Kennedy did not speak out frequently concerning civil rights. However, his brief term in office came at a tumultuous time in US history, when the matter of civil rights became the defining issue of a generation.

Mere months into his term, Kennedy faced his first major civil rights decision, concerning the 1961 Freedom Riders. That spring and summer hundreds of people rode southern interstate buses to oppose the practice of segregation, which had been outlawed on public buses. Some were arrested and attacked by local mobs. The violence and imprisonments brought the civil rights issue to national attention and showed that the federal government was not enforcing its own laws. In response, Kennedy sent federal marshals to guard the riders. Not wanting to lose support in the South though, he stressed that his decision was a legal issue, rather than a moral one.

The following year, Kennedy authorized federal troops to protect James Meredith, an African American attending the University of Mississippi. Though he insisted that it wouldn’t change his legislative plans. Then in 1963, as the movement became more violent and attracted international attention, Kennedy realized that stronger legislation would take the issue “out of the streets” and into the courts – away from international spectators. That February, he proposed a Civil Rights bill to Congress. He stated that it would have economic and diplomatic benefits, and argued that it should remove institutional racism because, “above all, it is wrong.”

Kennedy was further moved by the Birmingham campaign in May 1963, in which African American students staged nonviolent protests. Then on May 21, 1963, a federal judge ruled that the University of Alabama must allow two African American students to attend its summer courses. The governor of Alabama strongly opposed the order and insisted on making it a public display. On June 11, the students attempted to enter the school’s auditorium to register for classes, but the governor himself blocked the doorway. Kennedy then ordered federal troops to order him to step aside and allow the students to register.

In the wake of the nationally televised event, Kennedy decided it was time to address the nation on the civil rights issue. That night, at 8 p.m., Kennedy delivered his Civil Rights Address. He began by briefly talking about the events at the University of Alabama earlier in the day. Kennedy then stressed the importance that all Americans recognize civil rights as a moral cause that everyone should contribute to and that it was “as clear as the American Constitution.”

Kennedy’s address was well received by many people in the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King Jr. stated, “Can you believe that white man not only stepped up to the plate, he hit it over the fence!” Days later, on June 19, Kennedy sent his bill to Congress, saying its passage was “imperative.” Passage of the bill would be one of his major goals in the coming months.

Congress debated the bill and added a series of provisions to ban racial discrimination in employment, offer better protection to black voters, end segregation in all publicly owned buildings, and improve the anti-segregation clauses in regards to public facilities. Kennedy continued to push for the bill’s passage, but he wouldn’t live to see it, losing his life to an assassin’s bullet that November.

Upon taking office, Lyndon B. Johnson saw to it that Kennedy’s act be completed. Less than a week after becoming president, he addressed Congress, saying “No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy’s memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long.”

The House bill passed in February 1964, but Southern senators delayed the bill with a two-month filibuster. Hubert Humphrey, Everett Dirksen, and others submitted a new bill that they believed could get enough Republican swing votes to gain passage. Their new bill was accepted, passed, and signed into law by President Johnson on July 2, 1964.

Click here to read the full text of the act.