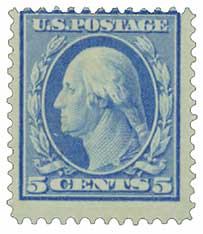

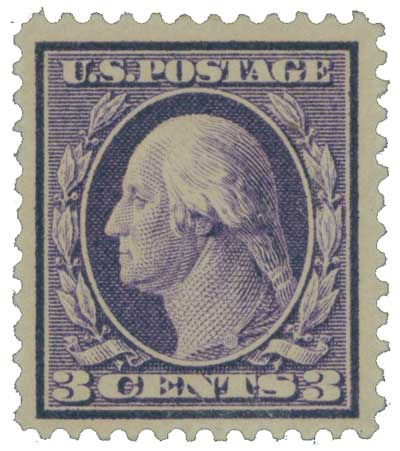

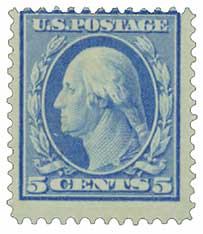

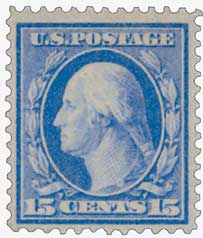

# 361 - 1909 5c Washington, blue

U.S. #361

1909 5¢ Washington

Bluish Paper

Earliest Known Use: May 18, 1910

Quantity issued: 4,000 (estimate)

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: Double line

Perforation: 12

Color: Blue

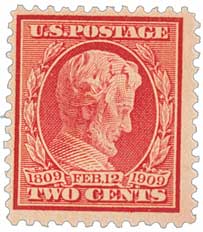

Like so many of the other stamps in the Washington-Franklin Series, this variety came about because of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing’s desire to create a better product. One of the main problems the Bureau was encountering was paper shrinkage. Since the stamps were wet printed they would shrink as the paper dried, causing irregular and “off center” perforations, which resulted in a considerable amount of waste.

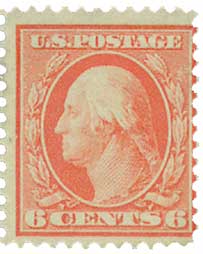

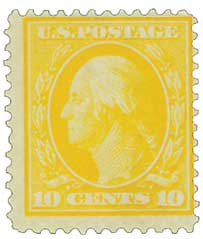

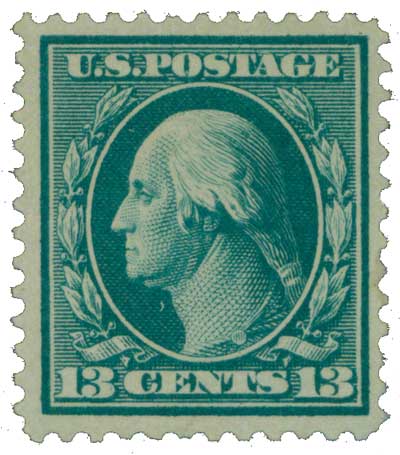

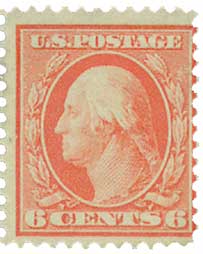

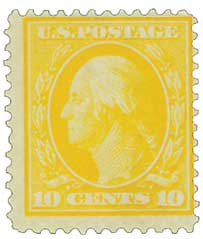

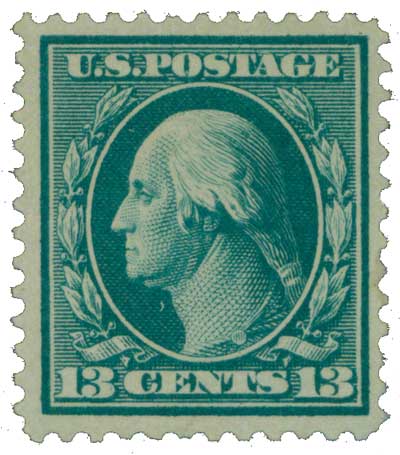

To combat the problem, the Bureau changed the composition of the paper by adding 35% wool rag to the wood pulp. Although stamps printed on this paper are known for having a bluish tint, the best way to check them is to examine the gum on the back. When compared with ordinary stamps, the yellow gum gives the stamp a grayish tone. Of the eight denominations printed on this new paper, the 6¢ orange and the 10¢ yellow are the easiest to distinguish, while the 13¢ blue-green is the hardest to locate and also the most desirable.

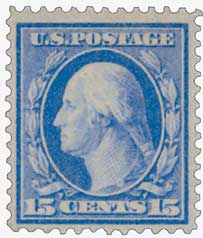

Since this paper was purely experimental and was not considered a new variety by the Postal Department, the stamps were simply distributed in their usual manner. Thus, the majority issued were used and lost to collectors, making these stamps quite scarce. Because there was a small demand for the 15¢ ultramarine issue (the highest denomination printed on this experimental paper), this stamp is the easiest to obtain.

On February 16, 1909, stamps printed on an experimental bluish paper were issued. These stamps were part of an effort to prevent paper shrinkage. In 1909, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing was having trouble with shrinkage of stamp paper. Since the stamps were wet printed, they would shrink as the paper dried, causing irregular and “off center” perforations. Some were so badly misaligned they had to be discarded! Some estimates report that as many as 20% of these stamps were destroyed because of misplaced perforations. To try to limit the waste from paper shrinkage, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing tried adding various components to the normal stamp paper. In one such experiment, about 1/3 rag stock was added to the wood pulp in hopes of reducing the shrinkage. The rag stock may have contained a small amount of dye, to make it easier to differentiate between the new experimental stamps and the regular issued stamps of 1908-09. Because of the slightly different paper color, these stamps have become known to collectors as “bluish-paper” stamps. Some of the first stamps printed on this paper were issued on February 16, 1909. Unfortunately for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the rag stock experiment was not successful in stopping paper shrinkage and was discontinued after a very short time. Consequently, few of the bluish-paper stamps were issued. Since this paper was purely experimental and was not considered a new variety by the Postal Department, the stamps were simply distributed in their usual manner. Thus, the majority issued were used and lost to collectors, making these stamps quite scarce. Although stamps printed on this paper are known for having a bluish tint, the best way to check them is to examine the gum on the back. When compared with ordinary stamps, the yellow gum gives the stamp a grayish tone. Of the stamps printed on this new paper, the 6¢ orange and the 10¢ yellow are the easiest to distinguish. The 4¢ orange brown and 8¢ olive green Washington are very scarce. The 13¢ blue green is the hardest to locate and also the most desirable. In fact, noted philatelic author and expert Max G. Johl called the 13¢ stamp “one of the rarities of the 20th century.” The only known #365s were discovered three years after their issue at the Saginaw, Michigan, post office by Assistant Postmaster John J. Spencer. Bureau of Engraving and Printing records state 4,000 were issued, but Spencer found evidence of only 1,000 stamps. In the years since, no other #365 stamps have been found! A controversy related to this paper involved Arthur Travers, who worked in the third assistant postmaster general’s office. He requested samples of all stamp values up to 15 cents printed on the bluish paper for post office archives. An investigation proved he had sold some of the sheets to a dealer for greater than face value. He was later fired.Bluish Paper Experiment

U.S. #361

1909 5¢ Washington

Bluish Paper

Earliest Known Use: May 18, 1910

Quantity issued: 4,000 (estimate)

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: Double line

Perforation: 12

Color: Blue

Like so many of the other stamps in the Washington-Franklin Series, this variety came about because of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing’s desire to create a better product. One of the main problems the Bureau was encountering was paper shrinkage. Since the stamps were wet printed they would shrink as the paper dried, causing irregular and “off center” perforations, which resulted in a considerable amount of waste.

To combat the problem, the Bureau changed the composition of the paper by adding 35% wool rag to the wood pulp. Although stamps printed on this paper are known for having a bluish tint, the best way to check them is to examine the gum on the back. When compared with ordinary stamps, the yellow gum gives the stamp a grayish tone. Of the eight denominations printed on this new paper, the 6¢ orange and the 10¢ yellow are the easiest to distinguish, while the 13¢ blue-green is the hardest to locate and also the most desirable.

Since this paper was purely experimental and was not considered a new variety by the Postal Department, the stamps were simply distributed in their usual manner. Thus, the majority issued were used and lost to collectors, making these stamps quite scarce. Because there was a small demand for the 15¢ ultramarine issue (the highest denomination printed on this experimental paper), this stamp is the easiest to obtain.

On February 16, 1909, stamps printed on an experimental bluish paper were issued. These stamps were part of an effort to prevent paper shrinkage. In 1909, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing was having trouble with shrinkage of stamp paper. Since the stamps were wet printed, they would shrink as the paper dried, causing irregular and “off center” perforations. Some were so badly misaligned they had to be discarded! Some estimates report that as many as 20% of these stamps were destroyed because of misplaced perforations. To try to limit the waste from paper shrinkage, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing tried adding various components to the normal stamp paper. In one such experiment, about 1/3 rag stock was added to the wood pulp in hopes of reducing the shrinkage. The rag stock may have contained a small amount of dye, to make it easier to differentiate between the new experimental stamps and the regular issued stamps of 1908-09. Because of the slightly different paper color, these stamps have become known to collectors as “bluish-paper” stamps. Some of the first stamps printed on this paper were issued on February 16, 1909. Unfortunately for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the rag stock experiment was not successful in stopping paper shrinkage and was discontinued after a very short time. Consequently, few of the bluish-paper stamps were issued. Since this paper was purely experimental and was not considered a new variety by the Postal Department, the stamps were simply distributed in their usual manner. Thus, the majority issued were used and lost to collectors, making these stamps quite scarce. Although stamps printed on this paper are known for having a bluish tint, the best way to check them is to examine the gum on the back. When compared with ordinary stamps, the yellow gum gives the stamp a grayish tone. Of the stamps printed on this new paper, the 6¢ orange and the 10¢ yellow are the easiest to distinguish. The 4¢ orange brown and 8¢ olive green Washington are very scarce. The 13¢ blue green is the hardest to locate and also the most desirable. In fact, noted philatelic author and expert Max G. Johl called the 13¢ stamp “one of the rarities of the 20th century.” The only known #365s were discovered three years after their issue at the Saginaw, Michigan, post office by Assistant Postmaster John J. Spencer. Bureau of Engraving and Printing records state 4,000 were issued, but Spencer found evidence of only 1,000 stamps. In the years since, no other #365 stamps have been found! A controversy related to this paper involved Arthur Travers, who worked in the third assistant postmaster general’s office. He requested samples of all stamp values up to 15 cents printed on the bluish paper for post office archives. An investigation proved he had sold some of the sheets to a dealer for greater than face value. He was later fired.Bluish Paper Experiment