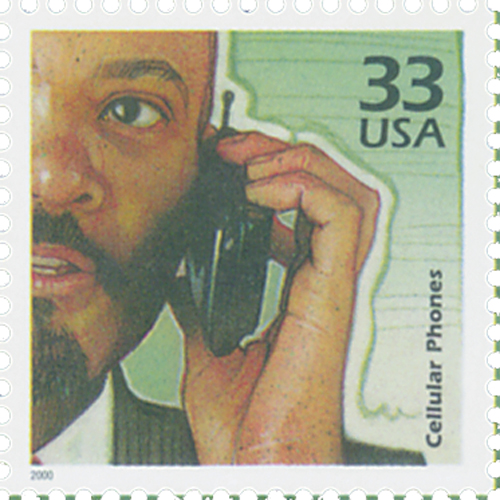

# 3191o FDC - 2000 33c Celebrate the Century - 1990s: Cellular Phones

Â

2000 33¢ Cellular Phones

Celebrate the Century – 1990s

City: Monterey, CA

Quantity:Â 8,250,000

Printed By: Ashton-Potter (USA) Ltd

Printing Method: Lithographed

Perforations: 11 ½

Color: Multicolored

First Official Transatlantic Phone CallÂ

On January 7, 1927, men in New York and London staged the first official telephone call across the Atlantic Ocean.

The conversation was over 50 years in the making. Some of the earliest experiments in telephone technology date back to the 1860s. Alexander Graham Bell first patented his telephone design in 1876 and the first telephone exchange was established in Hartford, Connecticut the following year.

Advancements continued, with the first call between two major cities (New York and Boston) taking place in 1883. While progress within America happened fast, attempts to have conversations across oceans posed a greater challenge. The first small victory to this effect came in 1915, when voices were transmitted between Virginia and Paris. Their messages were briefly sent, but they couldn’t have a conversation.

The following year brought another success, the first ship-to-shore conversation with a boat in the Atlantic. Then, a decade later, in 1926, the Bell company staged the first two-way conversation across the ocean. However, the attempt was simply a corporate experiment that would not be available commercially or to everyday people.

The following year, Bell (today’s AT&T) developed the service for commercial use. The service was set to begin on January 7, 1927, though a test call was placed the day before. On January 6, at 9:35 a.m. in New York (2:35 a.m. in London), an unnamed man in New York’s Bell building began the call, “Can you hear me now… I’m talking a little farther away from my transmitter… do you notice any difference now?†And over 3,000 miles away, an unnamed British man replied positively. The men went on to talk about the weather and the distances from England to India as well as New York to San Francisco. Then the American man said, “Distance doesn’t mean anything anymore. We are on the verge of a very high-speed world… people will use up their lives in a much shorter time, they won’t have to live so long.â€

The next day, January 7, 1927, the transatlantic telephone service officially began with a more formal conversation between Bell AT&T President W.S. Gifford and Sir Evelyn P. Murray, head of the British General post Office. Gifford began the conversation saying, “Today is the result of many years of research and experimentation. We open a telephonic path of speech between New York and London… That the people of these great cities will be brought within speaking distance to exchange views and facts as if they were face to face… No one can foresee the ultimate significance of this latest achievement of science and organization.â€

Murray then responded, calling it a “new epoch†of communication and declared the service open to “every telephone subscriber.†After their conversation, bankers, businessmen, and everyday people made a number of calls between New York and London curious about the new service. By day’s end, more than $6 million in new business was made and a news agency sent its first message from Europe to America.

These early transatlantic calls were made over radio waves, as it was too expensive and difficult to lay a cable all the way across the Atlantic. Because of this, calls were expensive – about $6 per minute. Eventually the technology improved and the transatlantic telephone cable improved service in 1956.

Click here to listen to Gifford and Murray’s conversation

Â

Â

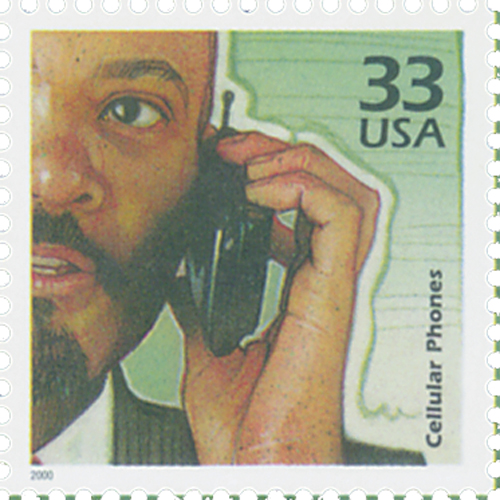

2000 33¢ Cellular Phones

Celebrate the Century – 1990s

City: Monterey, CA

Quantity:Â 8,250,000

Printed By: Ashton-Potter (USA) Ltd

Printing Method: Lithographed

Perforations: 11 ½

Color: Multicolored

First Official Transatlantic Phone CallÂ

On January 7, 1927, men in New York and London staged the first official telephone call across the Atlantic Ocean.

The conversation was over 50 years in the making. Some of the earliest experiments in telephone technology date back to the 1860s. Alexander Graham Bell first patented his telephone design in 1876 and the first telephone exchange was established in Hartford, Connecticut the following year.

Advancements continued, with the first call between two major cities (New York and Boston) taking place in 1883. While progress within America happened fast, attempts to have conversations across oceans posed a greater challenge. The first small victory to this effect came in 1915, when voices were transmitted between Virginia and Paris. Their messages were briefly sent, but they couldn’t have a conversation.

The following year brought another success, the first ship-to-shore conversation with a boat in the Atlantic. Then, a decade later, in 1926, the Bell company staged the first two-way conversation across the ocean. However, the attempt was simply a corporate experiment that would not be available commercially or to everyday people.

The following year, Bell (today’s AT&T) developed the service for commercial use. The service was set to begin on January 7, 1927, though a test call was placed the day before. On January 6, at 9:35 a.m. in New York (2:35 a.m. in London), an unnamed man in New York’s Bell building began the call, “Can you hear me now… I’m talking a little farther away from my transmitter… do you notice any difference now?†And over 3,000 miles away, an unnamed British man replied positively. The men went on to talk about the weather and the distances from England to India as well as New York to San Francisco. Then the American man said, “Distance doesn’t mean anything anymore. We are on the verge of a very high-speed world… people will use up their lives in a much shorter time, they won’t have to live so long.â€

The next day, January 7, 1927, the transatlantic telephone service officially began with a more formal conversation between Bell AT&T President W.S. Gifford and Sir Evelyn P. Murray, head of the British General post Office. Gifford began the conversation saying, “Today is the result of many years of research and experimentation. We open a telephonic path of speech between New York and London… That the people of these great cities will be brought within speaking distance to exchange views and facts as if they were face to face… No one can foresee the ultimate significance of this latest achievement of science and organization.â€

Murray then responded, calling it a “new epoch†of communication and declared the service open to “every telephone subscriber.†After their conversation, bankers, businessmen, and everyday people made a number of calls between New York and London curious about the new service. By day’s end, more than $6 million in new business was made and a news agency sent its first message from Europe to America.

These early transatlantic calls were made over radio waves, as it was too expensive and difficult to lay a cable all the way across the Atlantic. Because of this, calls were expensive – about $6 per minute. Eventually the technology improved and the transatlantic telephone cable improved service in 1956.

Click here to listen to Gifford and Murray’s conversation

Â