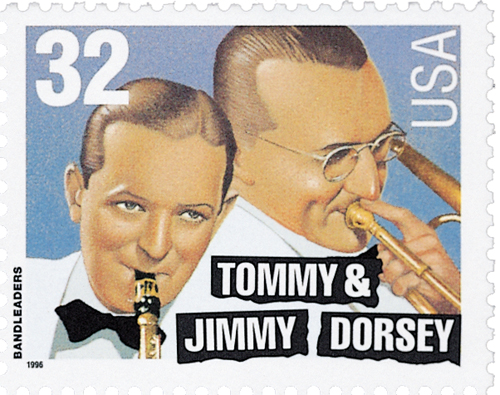

# 3186j FDC - 1999 33c Celebrate the Century - 1940s: The Big Band Sound

33¢ Big Band Sound

Celebrate the Century – 1940s

City: Dobbins AFB, GA

Printing Method: Lithographed, engraved

Perforations: 11.5

Color: Multicolored

Disappearance of Glenn Miller

On December 15, 1944, big band leader and composer Glenn Miller was aboard a plane that disappeared over the English Channel. Miller had put his successful civilian music career on hold to serve in the US Army during World War II.

Alton Glenn Miller was born on March 1, 1904, in Clarinda, Iowa. In 1915, his family moved to Grant City, Missouri, where he worked milking cows. Miller used the money from that job to buy his first trombone and join the town orchestra. He also played the cornet and mandolin. Miller’s family moved to Fort Morgan, Colorado, in 1918, where he attended high school. He was named Best Left End in Colorado for his performance on the football team. Miller also formed a band with some of his classmates and decided he wanted to become a professional musician.

Miller enrolled in the University of Colorado, but spent more time auditioning and playing shows and eventually dropped out. He studied with Joseph Schillinger and joined Ben Pollack’s band as a trombonist in 1926. By 1930 he was in demand as a free-lance musician in New York City. Soon he was organizing bands for big-name band leaders, including the Dorsey brothers and Ray Noble.

In 1937, Miller attempted to form his own orchestra, but failed. He was discouraged and went to New York City. Miller realized that if he was going to be successful, he needed to find a unique sound. He found that sound by blending one clarinet with four saxophones. Miller put a band together and within a year, they were an international success. The band played a mix of smooth, danceable ballads and crisp, driving swing numbers.

Miller’s band played Carnegie Hall in 1939 and played three times a week on CBS radio. His band also appeared in two movies – Sun Valley Serenade and Orchestra Wives. In 1942, Miller received the first gold record for “Chattanooga Choo-Choo.” Over the course of just four years, Miller had 16 number-one records and 69 top-ten hits – more than Elvis or the Beatles would have during their careers!

By 1942, Miller was at the height of his civilian career. But as the US joined the Second World War, he felt it was more important to join the war effort. Giving up his $15,000- to $20,0000-a-week income, Miller set his sights on military service.

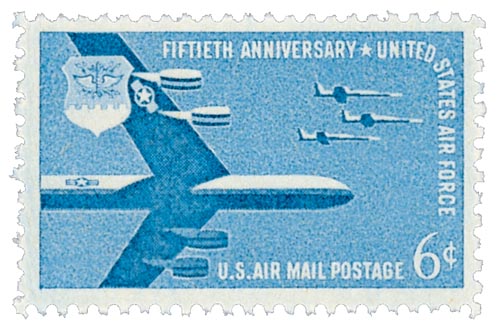

Too old to be drafted (at age 38), Miller first volunteered to join the Navy, but was told they didn’t need his services. He then wrote to the Army and asked to “be placed in charge of a modernized Army band.” His offer was accepted and he was soon transferred to the Army Air Force. There he served as assistant special services officer for the Army Air Forces Southeast Training Center at Maxwell Field in Montgomery, Alabama. He formed the Glenn Miller Army Air Force Band, which broadcast a weekly radio program, I Sustain the Wings, out of New York City.

Miller performed in service clubs and on radio programs, publicizing the activities of Maxwell’s civil service women aircraft mechanics. In Montgomery, Miller formed a large marching band and made strides to modernize military music. His “St. Louis Blue March” incorporated blues and jazz into the traditional military march.

In the summer of 1944, Miller traveled to England with his 50-piece Army Air Force Band. There he put on 800 shows and recorded at the famed Abbey Road Studios. Of his recordings there with Dinah Shore, General Jimmy Doolittle said, “next to a letter from home, that… was the greatest morale builder in the European Theater of Operations.” In addition to raising morale, some of Miller’s songs were performed in German and used as counter-propaganda to persuade the enemy to turn away from Nazism.

On December 15, 1944, Miller boarded a plane to cross the English Channel. He was headed to Paris to perform for the forces that had liberated the city. That night the plane disappeared and was never found. Miller’s wife accepted a Bronze Star medal on his behalf in March 1945. Miller is still listed as missing in action today. Two of the towns in which he grew up – Clarinda, Iowa, and Fort Morgan, Colorado – have annual festivals in his honor.

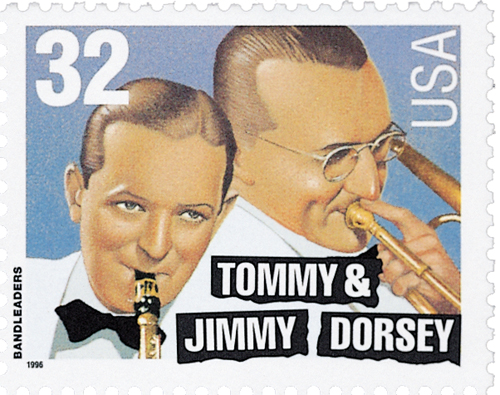

33¢ Big Band Sound

Celebrate the Century – 1940s

City: Dobbins AFB, GA

Printing Method: Lithographed, engraved

Perforations: 11.5

Color: Multicolored

Disappearance of Glenn Miller

On December 15, 1944, big band leader and composer Glenn Miller was aboard a plane that disappeared over the English Channel. Miller had put his successful civilian music career on hold to serve in the US Army during World War II.

Alton Glenn Miller was born on March 1, 1904, in Clarinda, Iowa. In 1915, his family moved to Grant City, Missouri, where he worked milking cows. Miller used the money from that job to buy his first trombone and join the town orchestra. He also played the cornet and mandolin. Miller’s family moved to Fort Morgan, Colorado, in 1918, where he attended high school. He was named Best Left End in Colorado for his performance on the football team. Miller also formed a band with some of his classmates and decided he wanted to become a professional musician.

Miller enrolled in the University of Colorado, but spent more time auditioning and playing shows and eventually dropped out. He studied with Joseph Schillinger and joined Ben Pollack’s band as a trombonist in 1926. By 1930 he was in demand as a free-lance musician in New York City. Soon he was organizing bands for big-name band leaders, including the Dorsey brothers and Ray Noble.

In 1937, Miller attempted to form his own orchestra, but failed. He was discouraged and went to New York City. Miller realized that if he was going to be successful, he needed to find a unique sound. He found that sound by blending one clarinet with four saxophones. Miller put a band together and within a year, they were an international success. The band played a mix of smooth, danceable ballads and crisp, driving swing numbers.

Miller’s band played Carnegie Hall in 1939 and played three times a week on CBS radio. His band also appeared in two movies – Sun Valley Serenade and Orchestra Wives. In 1942, Miller received the first gold record for “Chattanooga Choo-Choo.” Over the course of just four years, Miller had 16 number-one records and 69 top-ten hits – more than Elvis or the Beatles would have during their careers!

By 1942, Miller was at the height of his civilian career. But as the US joined the Second World War, he felt it was more important to join the war effort. Giving up his $15,000- to $20,0000-a-week income, Miller set his sights on military service.

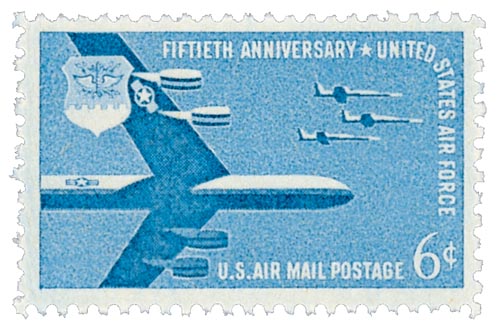

Too old to be drafted (at age 38), Miller first volunteered to join the Navy, but was told they didn’t need his services. He then wrote to the Army and asked to “be placed in charge of a modernized Army band.” His offer was accepted and he was soon transferred to the Army Air Force. There he served as assistant special services officer for the Army Air Forces Southeast Training Center at Maxwell Field in Montgomery, Alabama. He formed the Glenn Miller Army Air Force Band, which broadcast a weekly radio program, I Sustain the Wings, out of New York City.

Miller performed in service clubs and on radio programs, publicizing the activities of Maxwell’s civil service women aircraft mechanics. In Montgomery, Miller formed a large marching band and made strides to modernize military music. His “St. Louis Blue March” incorporated blues and jazz into the traditional military march.

In the summer of 1944, Miller traveled to England with his 50-piece Army Air Force Band. There he put on 800 shows and recorded at the famed Abbey Road Studios. Of his recordings there with Dinah Shore, General Jimmy Doolittle said, “next to a letter from home, that… was the greatest morale builder in the European Theater of Operations.” In addition to raising morale, some of Miller’s songs were performed in German and used as counter-propaganda to persuade the enemy to turn away from Nazism.

On December 15, 1944, Miller boarded a plane to cross the English Channel. He was headed to Paris to perform for the forces that had liberated the city. That night the plane disappeared and was never found. Miller’s wife accepted a Bronze Star medal on his behalf in March 1945. Miller is still listed as missing in action today. Two of the towns in which he grew up – Clarinda, Iowa, and Fort Morgan, Colorado – have annual festivals in his honor.