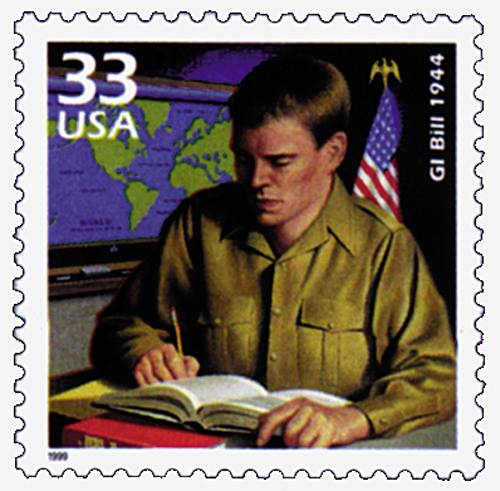

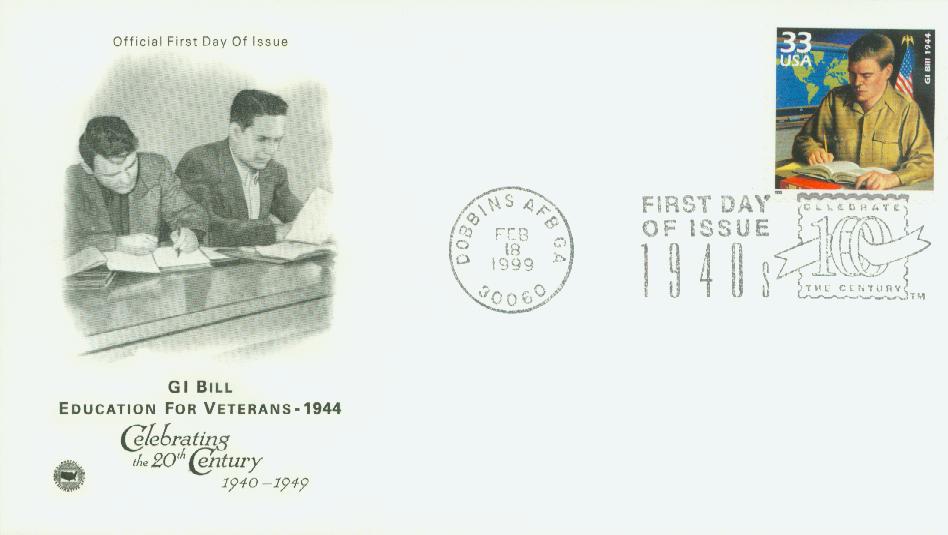

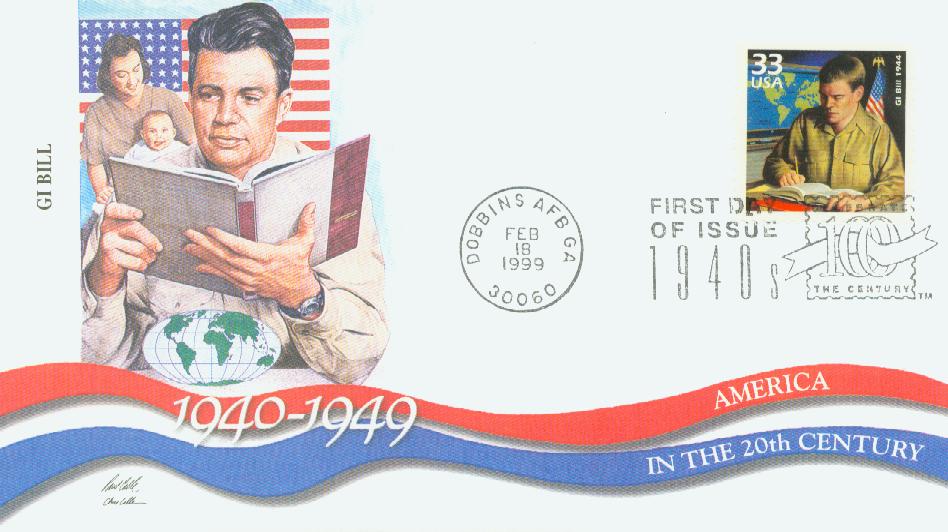

# 3186i FDC - 1999 33c Celebrate the Century - 1940s: GI Bill 1944

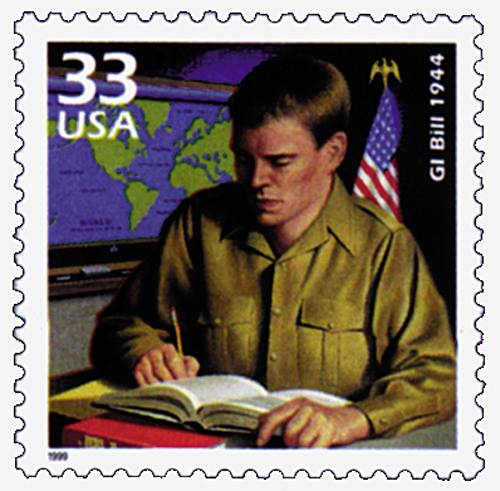

33¢ GI Bill

Celebrate the Century – 1940s

City: Dobbins AFB, GA

Printing Method: Lithographed, engraved

Perforations: 11.5

Color: Multicolored

GI Bill

On June 22, 1944, President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, also known as the GI Bill, into law.

When World War I veterans returned home, many had trouble finding jobs. Thousands of them flooded the labor market and most struggled to make a living, even with the government programs available.

To help alleviate the situation, Congress passed the Bonus Act of 1924, which offered veterans a bonus based on the number of days they had served in the military. However, the bonus wouldn’t be paid until 1945 – another 20 years – which would be little help to veterans at that time.

The Great Depression made the situation worse and by 1932, the out of work veterans were frustrated. On July 28, 1932, a group of 43,000 veterans and their families marched in Washington, DC, demanding they receive their bonus payments immediately. They called themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force and the media called them the Bonus Army.

President Herbert Hoover ordered the veterans removed from government property and Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur commanded infantry and tanks to force their removal. The following March, they held another Bonus March. This time, President Roosevelt offered them jobs with the Civilian Conservation Corp, which many of them took. And in 1936, Congress voted to award the veterans their bonus nine years early.

Needless to say, the situation wasn’t ideal, and as America entered World War II just a few years later, many looked for a better way to support our veterans when they returned home. Roosevelt was among those searching for an answer, as he wanted to expand the middle class and avoid the issues that followed the last war.

A major figure in the resulting GI Bill was American Legion National Commander Harry W. Colmery. He suggested offering benefits to all World War I veterans, male and female. Members of the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, as well as other veteran’s organizations, mobilized to encourage Congress to pass the bill. Ernest McFarland and Warren Atherton are considered the fathers of the GI Bill while Edith Nourse Rogers helped write and co-sponsor it and is considered the mother of the bill.

Initially, President Roosevelt suggested the bill offer one year of funding to poor veterans and four years of college to those that earned high marks on a written text. However, the final bill offered full benefits to all veterans, regardless of their wealth. The bill was introduced in January and signed into law on June 22, 1944.

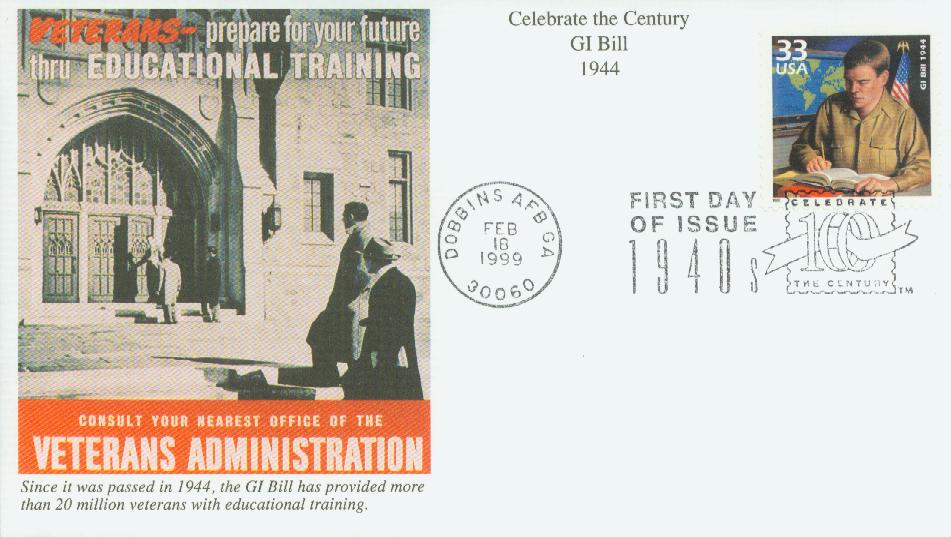

The GI Bill included paid tuition and living expenses for veterans to attend high school, college, or vocational schools. It also offered low-cost mortgages and low-interest loans to start businesses plus one year of unemployment compensation. Any veteran who had been on active duty for at least 90 days during the war and wasn’t dishonorably discharged was eligible – they didn’t need to have seen combat. They also didn’t have to pay income tax on their benefits.

By 1947, nearly half of all college admissions were veterans and by 1956, some 7.8 million veterans used their GI Bill to go to school. Veterans purchased mass-produced houses in the suburbs with low-interest government loans. Now living in new homes outside the city, they commuted in their new cars on new roads. Many supermarkets, restaurants, and retail stores also relocated. These post-World War II families were the first American middle class.

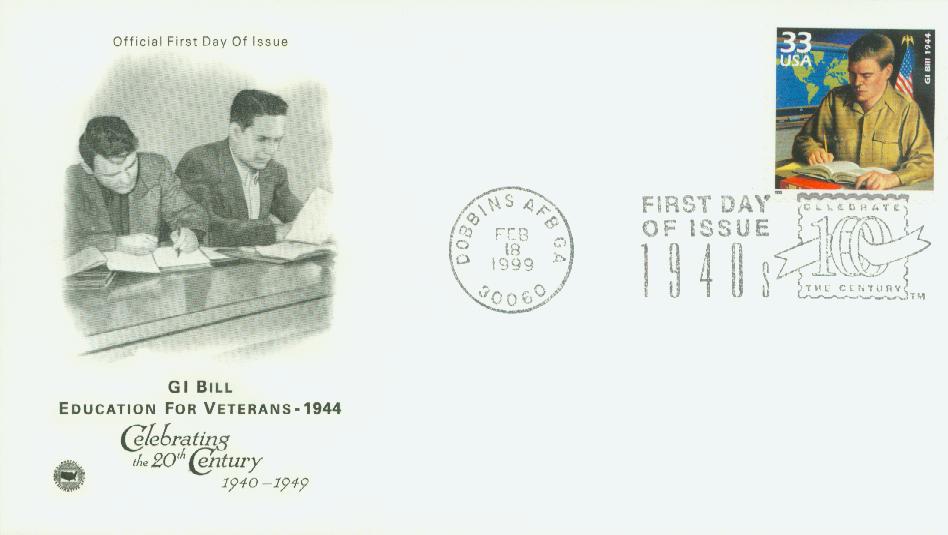

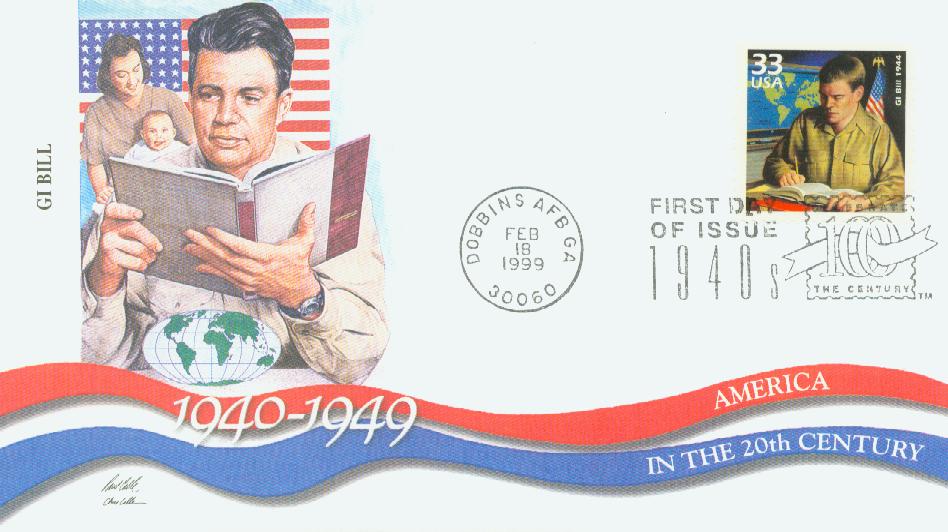

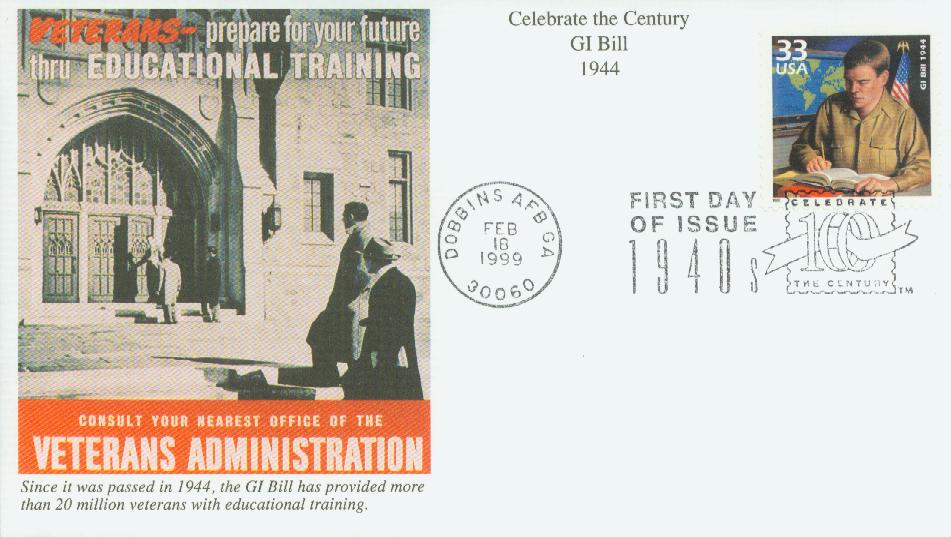

33¢ GI Bill

Celebrate the Century – 1940s

City: Dobbins AFB, GA

Printing Method: Lithographed, engraved

Perforations: 11.5

Color: Multicolored

GI Bill

On June 22, 1944, President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, also known as the GI Bill, into law.

When World War I veterans returned home, many had trouble finding jobs. Thousands of them flooded the labor market and most struggled to make a living, even with the government programs available.

To help alleviate the situation, Congress passed the Bonus Act of 1924, which offered veterans a bonus based on the number of days they had served in the military. However, the bonus wouldn’t be paid until 1945 – another 20 years – which would be little help to veterans at that time.

The Great Depression made the situation worse and by 1932, the out of work veterans were frustrated. On July 28, 1932, a group of 43,000 veterans and their families marched in Washington, DC, demanding they receive their bonus payments immediately. They called themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force and the media called them the Bonus Army.

President Herbert Hoover ordered the veterans removed from government property and Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur commanded infantry and tanks to force their removal. The following March, they held another Bonus March. This time, President Roosevelt offered them jobs with the Civilian Conservation Corp, which many of them took. And in 1936, Congress voted to award the veterans their bonus nine years early.

Needless to say, the situation wasn’t ideal, and as America entered World War II just a few years later, many looked for a better way to support our veterans when they returned home. Roosevelt was among those searching for an answer, as he wanted to expand the middle class and avoid the issues that followed the last war.

A major figure in the resulting GI Bill was American Legion National Commander Harry W. Colmery. He suggested offering benefits to all World War I veterans, male and female. Members of the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, as well as other veteran’s organizations, mobilized to encourage Congress to pass the bill. Ernest McFarland and Warren Atherton are considered the fathers of the GI Bill while Edith Nourse Rogers helped write and co-sponsor it and is considered the mother of the bill.

Initially, President Roosevelt suggested the bill offer one year of funding to poor veterans and four years of college to those that earned high marks on a written text. However, the final bill offered full benefits to all veterans, regardless of their wealth. The bill was introduced in January and signed into law on June 22, 1944.

The GI Bill included paid tuition and living expenses for veterans to attend high school, college, or vocational schools. It also offered low-cost mortgages and low-interest loans to start businesses plus one year of unemployment compensation. Any veteran who had been on active duty for at least 90 days during the war and wasn’t dishonorably discharged was eligible – they didn’t need to have seen combat. They also didn’t have to pay income tax on their benefits.

By 1947, nearly half of all college admissions were veterans and by 1956, some 7.8 million veterans used their GI Bill to go to school. Veterans purchased mass-produced houses in the suburbs with low-interest government loans. Now living in new homes outside the city, they commuted in their new cars on new roads. Many supermarkets, restaurants, and retail stores also relocated. These post-World War II families were the first American middle class.