# 2869m FDC - 1994 29c Legends of the West: Geronimo

U.S. #2869m

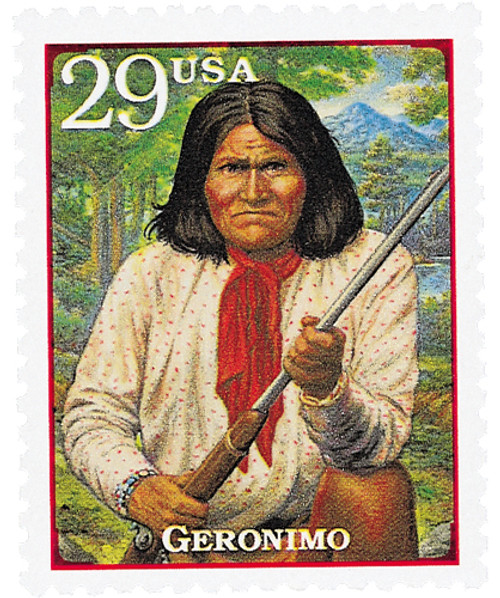

1994 29¢ Geronimo

Legends of the West

- From the corrected version of the famed Legends of the West error sheet

- First sheet in the Classic Collection Series

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Legends of the West

Value: 29¢, rate for first-class mail

First Day of Issue: October 18, 1994

First Day Cities: Tucson, Arizona; Lawton, Oklahoma; Laramie, Wyoming

Quantity Issued: 19,282,800

Printed by: Stamp Venturers

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Panes of 20 in sheets of 120

Perforations: 10.2 x 10.1

Why the stamp was issued: The Legends of the West sheet was the first issue in the Classic Collection Series. It was developed from an idea to honor “Western Americana.”

About the stamp design: Stamp artist Mark Hess spent nearly two years working on the Legends of the West stamps. The Geronimo stamp was based on one of the most well-known photos of the Apache warrior, taken in 1884. He’s pictured in front of a forest and mountain, though some said this was incorrect as he was a “desert Indian,” but Hess believed his background was accurate.

Special design details: This stamp comes from the famed Legends of the West sheet, which made headlines due to two mistakes made by the United States Postal Service and led to a string of events without precedent in the history of US stamp collecting.

One of the people to be featured on the sheet was black rodeo star Bill Pickett. After the stamps were announced, but not officially issued, a radio reporter phoned Frank Phillips Jr., great-grandson of Bill Pickett, and asked him about the stamp. Phillips went to his local post office, looked at the design and recognized it as Ben Pickett – Bill’s brother and business associate. The stamp pictured the wrong man! That was the first mistake.

Phillips complained to the Postal Service and Postmaster General Marvin Runyon issued an order to recall and destroy the error stamps. Runyon also ordered new revised stamps be created – these are the corrected Legends of the West stamps – #2869.

But before the recall, 186 error sheets were sold by postal workers – before the official “first day of issue.” This was the second mistake. These error sheets were being resold for sums ranging from $3,000 to $15,000 each!

Several weeks later the US Postal Service announced that 150,000 error sheets would be sold at face value by means of a mail order lottery. This unprecedented move was made with the permission of Frank Phillips Jr. so the Post Office could recover its printing cost and not lose money. Sales were limited to one per household. The remaining stamps were destroyed.

About the printing process: In order to include the text on the back of the Legends of the West stamps, it had to be printed under the gum, so that it would still be visible if a stamp was soaked off an envelope. Because people would need to lick the stamps, the ink had to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration as non-toxic. The printer also used an extra-fine 300-line screen, which resulted in some of the highest-quality gravure stamp printings in recent years.

First Day Cities: The Laramie, Wyoming First Day ceremony was held at the University of Wyoming. The Tucson, Arizona ceremony was held at the Old Tucson Studios, where the High Chaparral TV series and several Western movies had been filmed. The Lawton, Oklahoma ceremony was held at Fort Sill, where Geronimo was buried.

About the Legends of the West: The Legends of the West sheet was ultimately born out of a discussion to issue a stamp to honor the 100th anniversary of Ellis Island in 1992. That plan was abandoned, but was Ellis Island was featured on a postal card in the Historic Preservation Series (#UX165). Talks then pivoted to a stamp honoring “Western Americana.” Stamp artist Mark Hess was tasked with producing four semi-jumbo stamp images capturing the colorful and graphic look of old Wild West show posters. The Citizens Stamp Advisory Committee (CSAC) discussed Hess’ images and decided to expand on the idea and honor 16 significant men and women that played major roles in the expansion of the West. At one point, they considered outlaws such as Butch Cassidy, Billy the Kid, and Jesse James, but ultimately decided to “come down on the side of right and justice.” The sheet of 20 had a decorative header and descriptive text was included on the back of each stamp.

The Legends of the West stamp designs were also adapted to postal cards, #UX178-97.

History the stamp represents:

Geronimo was born on June 16, 1829, in present-day Arizona, in a region claimed by both Mexico and the Apache Indians. A Chiricahua Apache, Geronimo’s given Native American name was Goyaalé – “the one who yawns.” A talented hunter, he claimed to have swallowed the heart of his first kill to guarantee a successful life on the run. Coming from a small tribe of just 8,000 Apaches, he was often surrounded by enemies and proved to be a talented raider – leading four successful raids by the time he was 17.

That same year, Geronimo married a woman named Alope and began a family. In 1851, while Geronimo and other men of his tribe were in town trading goods, a band of Mexicans attacked their camp. Geronimo’s mother, wife and all three of his children were killed – unleashing a fury that would drive him to destroy his enemies. When U.S. troops and settlers began moving in on Apache land, Geronimo fought back with the same vengeance. Although he was outnumbered, Geronimo fought for over thirty years, becoming famous for his bravery and cunning. He was described as having the “eye of a hawk, the stealth of a coyote, and the courage of a tiger.”

During one battle he repeatedly ran through a hail of bullets to kill Mexican soldiers with his knife. Seeing the warrior running towards them, the soldiers began to yell out “Geronimo!” – most likely a plea to St. Jerome to spare their lives, though possibly a mispronunciation of his given name.

In 1876, the Chiricahuas were moved to a reservation in San Carlos, Arizona. But Geronimo, refusing to give up his freedom, fled with 700 followers. One of the most feared and respected Indian warriors, Geronimo fought overwhelming odds in trying to win freedom for his people. He eluded the authorities for nearly ten years. During that time, he faked surrender on three occasions, but fled at the last moment.

But by the late 1880s, his band included only 38 men, women and children. After decades of fighting and years of running dozens of miles a day, Geronimo and his followers were tired. In September 1886, Geronimo surrendered for the fourth and last time, after more than 5,000 troops had been deployed against him. He was the last Indian warrior to do so, ending the major fighting in the Indian Wars in the Southwest.

Geronimo spent several years as a prisoner of war in Florida and Alabama. In 1894, Geronimo and his followers were moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma and given farmland on the Kiowa Comanche Reservation. Four years later, he was part of a delegation that attended the Trans-Mississippi International Exposition in Nebraska. Americans had learned about Geronimo’s exploits during the Apache Wars and were curious to see the warrior in person. Geronimo quickly achieved celebrity status there and was frequently invited to subsequent fairs in the coming years. Among the largest were the Pan-American Expo in New York and the Louisiana Purchase Expo in Missouri. Geronimo attended these expos in his traditional warrior clothing, posed for pictures, and sold his crafts.

Geronimo met President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904, and was among a group of Indian chiefs to ride in his inaugural parade. Geronimo asked the president to allow his people to return to their homeland in Arizona, but Roosevelt refused, as tensions were still high from casualties his people inflicted decades earlier. Five years later, Geronimo was thrown from his horse while riding home and spent the night out in the cold. Though a friend found him the next morning and brought him home, Geronimo was in poor health and he died six days later on February 17, 1909. In his final days he admitted, “I should never have surrendered. I should have fought until I was the last man alive.”

U.S. #2869m

1994 29¢ Geronimo

Legends of the West

- From the corrected version of the famed Legends of the West error sheet

- First sheet in the Classic Collection Series

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Legends of the West

Value: 29¢, rate for first-class mail

First Day of Issue: October 18, 1994

First Day Cities: Tucson, Arizona; Lawton, Oklahoma; Laramie, Wyoming

Quantity Issued: 19,282,800

Printed by: Stamp Venturers

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Panes of 20 in sheets of 120

Perforations: 10.2 x 10.1

Why the stamp was issued: The Legends of the West sheet was the first issue in the Classic Collection Series. It was developed from an idea to honor “Western Americana.”

About the stamp design: Stamp artist Mark Hess spent nearly two years working on the Legends of the West stamps. The Geronimo stamp was based on one of the most well-known photos of the Apache warrior, taken in 1884. He’s pictured in front of a forest and mountain, though some said this was incorrect as he was a “desert Indian,” but Hess believed his background was accurate.

Special design details: This stamp comes from the famed Legends of the West sheet, which made headlines due to two mistakes made by the United States Postal Service and led to a string of events without precedent in the history of US stamp collecting.

One of the people to be featured on the sheet was black rodeo star Bill Pickett. After the stamps were announced, but not officially issued, a radio reporter phoned Frank Phillips Jr., great-grandson of Bill Pickett, and asked him about the stamp. Phillips went to his local post office, looked at the design and recognized it as Ben Pickett – Bill’s brother and business associate. The stamp pictured the wrong man! That was the first mistake.

Phillips complained to the Postal Service and Postmaster General Marvin Runyon issued an order to recall and destroy the error stamps. Runyon also ordered new revised stamps be created – these are the corrected Legends of the West stamps – #2869.

But before the recall, 186 error sheets were sold by postal workers – before the official “first day of issue.” This was the second mistake. These error sheets were being resold for sums ranging from $3,000 to $15,000 each!

Several weeks later the US Postal Service announced that 150,000 error sheets would be sold at face value by means of a mail order lottery. This unprecedented move was made with the permission of Frank Phillips Jr. so the Post Office could recover its printing cost and not lose money. Sales were limited to one per household. The remaining stamps were destroyed.

About the printing process: In order to include the text on the back of the Legends of the West stamps, it had to be printed under the gum, so that it would still be visible if a stamp was soaked off an envelope. Because people would need to lick the stamps, the ink had to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration as non-toxic. The printer also used an extra-fine 300-line screen, which resulted in some of the highest-quality gravure stamp printings in recent years.

First Day Cities: The Laramie, Wyoming First Day ceremony was held at the University of Wyoming. The Tucson, Arizona ceremony was held at the Old Tucson Studios, where the High Chaparral TV series and several Western movies had been filmed. The Lawton, Oklahoma ceremony was held at Fort Sill, where Geronimo was buried.

About the Legends of the West: The Legends of the West sheet was ultimately born out of a discussion to issue a stamp to honor the 100th anniversary of Ellis Island in 1992. That plan was abandoned, but was Ellis Island was featured on a postal card in the Historic Preservation Series (#UX165). Talks then pivoted to a stamp honoring “Western Americana.” Stamp artist Mark Hess was tasked with producing four semi-jumbo stamp images capturing the colorful and graphic look of old Wild West show posters. The Citizens Stamp Advisory Committee (CSAC) discussed Hess’ images and decided to expand on the idea and honor 16 significant men and women that played major roles in the expansion of the West. At one point, they considered outlaws such as Butch Cassidy, Billy the Kid, and Jesse James, but ultimately decided to “come down on the side of right and justice.” The sheet of 20 had a decorative header and descriptive text was included on the back of each stamp.

The Legends of the West stamp designs were also adapted to postal cards, #UX178-97.

History the stamp represents:

Geronimo was born on June 16, 1829, in present-day Arizona, in a region claimed by both Mexico and the Apache Indians. A Chiricahua Apache, Geronimo’s given Native American name was Goyaalé – “the one who yawns.” A talented hunter, he claimed to have swallowed the heart of his first kill to guarantee a successful life on the run. Coming from a small tribe of just 8,000 Apaches, he was often surrounded by enemies and proved to be a talented raider – leading four successful raids by the time he was 17.

That same year, Geronimo married a woman named Alope and began a family. In 1851, while Geronimo and other men of his tribe were in town trading goods, a band of Mexicans attacked their camp. Geronimo’s mother, wife and all three of his children were killed – unleashing a fury that would drive him to destroy his enemies. When U.S. troops and settlers began moving in on Apache land, Geronimo fought back with the same vengeance. Although he was outnumbered, Geronimo fought for over thirty years, becoming famous for his bravery and cunning. He was described as having the “eye of a hawk, the stealth of a coyote, and the courage of a tiger.”

During one battle he repeatedly ran through a hail of bullets to kill Mexican soldiers with his knife. Seeing the warrior running towards them, the soldiers began to yell out “Geronimo!” – most likely a plea to St. Jerome to spare their lives, though possibly a mispronunciation of his given name.

In 1876, the Chiricahuas were moved to a reservation in San Carlos, Arizona. But Geronimo, refusing to give up his freedom, fled with 700 followers. One of the most feared and respected Indian warriors, Geronimo fought overwhelming odds in trying to win freedom for his people. He eluded the authorities for nearly ten years. During that time, he faked surrender on three occasions, but fled at the last moment.

But by the late 1880s, his band included only 38 men, women and children. After decades of fighting and years of running dozens of miles a day, Geronimo and his followers were tired. In September 1886, Geronimo surrendered for the fourth and last time, after more than 5,000 troops had been deployed against him. He was the last Indian warrior to do so, ending the major fighting in the Indian Wars in the Southwest.

Geronimo spent several years as a prisoner of war in Florida and Alabama. In 1894, Geronimo and his followers were moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma and given farmland on the Kiowa Comanche Reservation. Four years later, he was part of a delegation that attended the Trans-Mississippi International Exposition in Nebraska. Americans had learned about Geronimo’s exploits during the Apache Wars and were curious to see the warrior in person. Geronimo quickly achieved celebrity status there and was frequently invited to subsequent fairs in the coming years. Among the largest were the Pan-American Expo in New York and the Louisiana Purchase Expo in Missouri. Geronimo attended these expos in his traditional warrior clothing, posed for pictures, and sold his crafts.

Geronimo met President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904, and was among a group of Indian chiefs to ride in his inaugural parade. Geronimo asked the president to allow his people to return to their homeland in Arizona, but Roosevelt refused, as tensions were still high from casualties his people inflicted decades earlier. Five years later, Geronimo was thrown from his horse while riding home and spent the night out in the cold. Though a friend found him the next morning and brought him home, Geronimo was in poor health and he died six days later on February 17, 1909. In his final days he admitted, “I should never have surrendered. I should have fought until I was the last man alive.”