1895 50c Jefferson, double line watermark

# 275 - 1895 50c Jefferson, double line watermark

$32.00 - $425.00

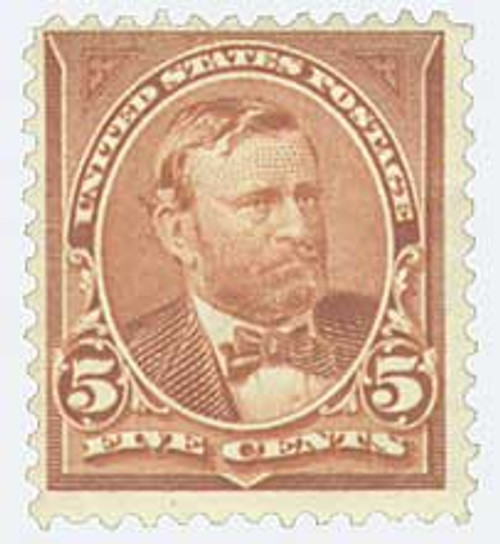

U.S. #275

1895 50¢ Jefferson

1895 50¢ Jefferson

Issued: November 9, 1895

Issue Quantity: 1,065,390

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: Double line USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Orange

U.S. #275 can be easily distinguished from U.S. #260 of the 1894 Bureau Issues by its color. The 1895 stamp is a red orange shade that isn’t found in the earlier stamps.

Issue Quantity: 1,065,390

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: Double line USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Orange

U.S. #275 can be easily distinguished from U.S. #260 of the 1894 Bureau Issues by its color. The 1895 stamp is a red orange shade that isn’t found in the earlier stamps.

After the Spanish-American War, U.S. #275 stamps were overprinted for use in Guam and the Philippines. 4,000 U.S. #275 stamps were overprinted for use in Guam alone.

The ship carrying the first supply of the overprinted 50¢ Jefferson stamps to the Philippines was sunk, destroying 50,000 of the stamps. A second shipment was dispatched. It also included a large quantity of the unwatermarked 1894 50¢ stamps.

Why Watermarks Were Added in 1895

The United States printed stamps on watermarked paper from 1895 to 1915. The watermarks, consisting of the letters “USPS” (for United States Postal Service), were faint patterns impressed into the paper during its manufacture. Often only a single letter or a portion of a letter is found on a single stamp.

Since the special watermark paper may already have been ordered at the time of the “Chicago Counterfeits,” the Postal Department may have anticipated the possibility before it actually happened. Other nations had used watermarking earlier.

The “USPS” watermarks are in single line or double line letters. To see a watermark, put the stamp in a watermark tray and add a few drops of watermark fluid. The mark (or part of it) should show clearly, though it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between single and double line watermarks.

The Chicago Counterfeits

The “Chicago Counterfeits,” as the scandal came to be known, was one of the few counterfeits in the history of U.S. postage stamps. The Post Office Department was made aware of the matter when Edward Lowry contacted Postal Inspector James Stuart. Lowry wanted to know if the Postal Department had any objection to his purchasing the 2¢ current issue at less than face value, as advertised in the Chicago Tribune. The ad read, “We have $115 U.S. two cent stamps which we cannot use here, will send them by express C.O.D. privilege of examination for $100. Canadian Novelty Supply Agency, Hamilton, Ontario, Can.” In essence, they were offering 5,750 stamps worth $115 for $100. The deal sounded suspicious to Inspector Stuart, and in cooperation with Lowry, had him send a request for the stamps.

At about the same time, Nathan Herman called the ad to the attention of U.S. Secret Service agent, Captain Thomas Porter, who joined forces with Inspector Stuart. The agents also had Herman write for a package of stamps. On April 8, 1895, the stamps, which Lowry and Herman had ordered, arrived at the Chicago office of the Wells Fargo Express Company. In addition, five other similar packages arrived, ordered by other people who had seen the ad. Interestingly enough, each of them had received the proper number of stamps. Over 40,000 stamps were confiscated that day!

Meanwhile, on April 6th, Captain Porter was notified that a Mrs. Lacy and her daughter, Tinsa McMillan, had some sort of printing operation set up in a back room of their apartment. When Porter, along with several agents and police officers, searched the apartment later that same evening, they found a copying camera, a perforating machine, copper printing plates, gummed paper, and other paraphernalia for producing stamps. Suspecting they were on the right track, he and Inspector Stuart traveled to Hamilton, Ontario, where they arrested Tinsa McMillan at the office of the Canadian Novelty Supply Company. As head of the organization, she had organized and directed the entire affair, and was sentenced to a year and a half in a reformatory.

A Mr. George Morrison was also arrested over a week later at his downtown Chicago office. A printing press was found there, but no other supplies. Apparently, the stamps were printed at his office and then shipped to Canada.

Seven months later, a Mr. Warren Thompson was arrested. The owner and editor of a magazine called Heart and Hand, he had assisted in making the stamps and was using them as postage on his periodical as a test to determine if the stamps would be discovered when passing through the mail. Thirty thousand more counterfeit stamps were confiscated, bringing the total up to over 70,000 confiscated stamps!

Watermarked Stamps

After the 1895 counterfeiting scam, the Post Office Department made the decision to print the stamps on watermarked paper. A watermark is a pattern impressed into the paper during its manufacture. While still in the wet pulp stage, the paper passes through a “dandy roller” which has “bits” attached to it. These bits are pressed into the paper, causing a slight thinning, and thus imprinting the design.

Beginning with the first postage stamp, watermarks were used to discourage counterfeiting. Britain’s Penny Black was watermarked with a small, simple crown. Various other designs were used until 1967, when Britain produced its first stamp on unwatermarked paper. Today, many British commonwealth countries still use watermarks. The designs range from letters to symbols or emblems, from the simple to the intricate.

The first U.S. watermark consisted of the letters USPS (United States Postal Service) and is described as being “double-lined.” The letters were repeated across the entire sheet, and as a result, only a portion of one or more letters will appear on a stamp. Occasionally, a stamp will have a complete letter on it. When the stamps were printed, no thought was given to the position of the watermark. Consequently, the watermark may be backwards, upside-down, backwards and upside-down, or sideways in relation to the stamp. None are unusual or considered a separate variety.

Errors were made, however, on the 6¢ Garfield and the 8¢ Sherman, when some of the stamps were printed on sheets watermarked USIR (United States Internal Revenue). Since the BEP printed regular issue postage stamps, as well as revenue stamps, it’s easy to see how such a mistake may have happened. Some believe the switch may have been deliberate, because not enough properly marked paper was available.

A watermark can be identified by holding the stamp up to a light source, or with the aid of a watermark tray and benzine fluid. When the stamps are printed on a colored background, as the 1895 series is, the latter method is preferred. The stamp is placed face down in the tray, and a small drop of solution is dropped onto it. As the liquid penetrates the paper, the watermark will show up briefly, as the thinner paper is penetrated first.

U.S. #275

1895 50¢ Jefferson

1895 50¢ Jefferson

Issued: November 9, 1895

Issue Quantity: 1,065,390

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: Double line USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Orange

U.S. #275 can be easily distinguished from U.S. #260 of the 1894 Bureau Issues by its color. The 1895 stamp is a red orange shade that isn’t found in the earlier stamps.

Issue Quantity: 1,065,390

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: Double line USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Orange

U.S. #275 can be easily distinguished from U.S. #260 of the 1894 Bureau Issues by its color. The 1895 stamp is a red orange shade that isn’t found in the earlier stamps.

After the Spanish-American War, U.S. #275 stamps were overprinted for use in Guam and the Philippines. 4,000 U.S. #275 stamps were overprinted for use in Guam alone.

The ship carrying the first supply of the overprinted 50¢ Jefferson stamps to the Philippines was sunk, destroying 50,000 of the stamps. A second shipment was dispatched. It also included a large quantity of the unwatermarked 1894 50¢ stamps.

Why Watermarks Were Added in 1895

The United States printed stamps on watermarked paper from 1895 to 1915. The watermarks, consisting of the letters “USPS” (for United States Postal Service), were faint patterns impressed into the paper during its manufacture. Often only a single letter or a portion of a letter is found on a single stamp.

Since the special watermark paper may already have been ordered at the time of the “Chicago Counterfeits,” the Postal Department may have anticipated the possibility before it actually happened. Other nations had used watermarking earlier.

The “USPS” watermarks are in single line or double line letters. To see a watermark, put the stamp in a watermark tray and add a few drops of watermark fluid. The mark (or part of it) should show clearly, though it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between single and double line watermarks.

The Chicago Counterfeits

The “Chicago Counterfeits,” as the scandal came to be known, was one of the few counterfeits in the history of U.S. postage stamps. The Post Office Department was made aware of the matter when Edward Lowry contacted Postal Inspector James Stuart. Lowry wanted to know if the Postal Department had any objection to his purchasing the 2¢ current issue at less than face value, as advertised in the Chicago Tribune. The ad read, “We have $115 U.S. two cent stamps which we cannot use here, will send them by express C.O.D. privilege of examination for $100. Canadian Novelty Supply Agency, Hamilton, Ontario, Can.” In essence, they were offering 5,750 stamps worth $115 for $100. The deal sounded suspicious to Inspector Stuart, and in cooperation with Lowry, had him send a request for the stamps.

At about the same time, Nathan Herman called the ad to the attention of U.S. Secret Service agent, Captain Thomas Porter, who joined forces with Inspector Stuart. The agents also had Herman write for a package of stamps. On April 8, 1895, the stamps, which Lowry and Herman had ordered, arrived at the Chicago office of the Wells Fargo Express Company. In addition, five other similar packages arrived, ordered by other people who had seen the ad. Interestingly enough, each of them had received the proper number of stamps. Over 40,000 stamps were confiscated that day!

Meanwhile, on April 6th, Captain Porter was notified that a Mrs. Lacy and her daughter, Tinsa McMillan, had some sort of printing operation set up in a back room of their apartment. When Porter, along with several agents and police officers, searched the apartment later that same evening, they found a copying camera, a perforating machine, copper printing plates, gummed paper, and other paraphernalia for producing stamps. Suspecting they were on the right track, he and Inspector Stuart traveled to Hamilton, Ontario, where they arrested Tinsa McMillan at the office of the Canadian Novelty Supply Company. As head of the organization, she had organized and directed the entire affair, and was sentenced to a year and a half in a reformatory.

A Mr. George Morrison was also arrested over a week later at his downtown Chicago office. A printing press was found there, but no other supplies. Apparently, the stamps were printed at his office and then shipped to Canada.

Seven months later, a Mr. Warren Thompson was arrested. The owner and editor of a magazine called Heart and Hand, he had assisted in making the stamps and was using them as postage on his periodical as a test to determine if the stamps would be discovered when passing through the mail. Thirty thousand more counterfeit stamps were confiscated, bringing the total up to over 70,000 confiscated stamps!

Watermarked Stamps

After the 1895 counterfeiting scam, the Post Office Department made the decision to print the stamps on watermarked paper. A watermark is a pattern impressed into the paper during its manufacture. While still in the wet pulp stage, the paper passes through a “dandy roller” which has “bits” attached to it. These bits are pressed into the paper, causing a slight thinning, and thus imprinting the design.

Beginning with the first postage stamp, watermarks were used to discourage counterfeiting. Britain’s Penny Black was watermarked with a small, simple crown. Various other designs were used until 1967, when Britain produced its first stamp on unwatermarked paper. Today, many British commonwealth countries still use watermarks. The designs range from letters to symbols or emblems, from the simple to the intricate.

The first U.S. watermark consisted of the letters USPS (United States Postal Service) and is described as being “double-lined.” The letters were repeated across the entire sheet, and as a result, only a portion of one or more letters will appear on a stamp. Occasionally, a stamp will have a complete letter on it. When the stamps were printed, no thought was given to the position of the watermark. Consequently, the watermark may be backwards, upside-down, backwards and upside-down, or sideways in relation to the stamp. None are unusual or considered a separate variety.

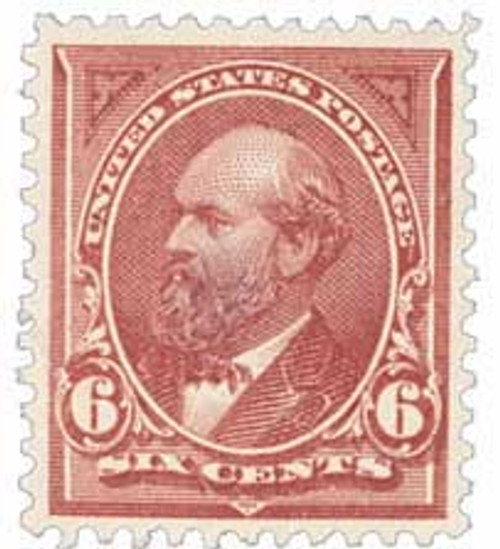

Errors were made, however, on the 6¢ Garfield and the 8¢ Sherman, when some of the stamps were printed on sheets watermarked USIR (United States Internal Revenue). Since the BEP printed regular issue postage stamps, as well as revenue stamps, it’s easy to see how such a mistake may have happened. Some believe the switch may have been deliberate, because not enough properly marked paper was available.

A watermark can be identified by holding the stamp up to a light source, or with the aid of a watermark tray and benzine fluid. When the stamps are printed on a colored background, as the 1895 series is, the latter method is preferred. The stamp is placed face down in the tray, and a small drop of solution is dropped onto it. As the liquid penetrates the paper, the watermark will show up briefly, as the thinner paper is penetrated first.