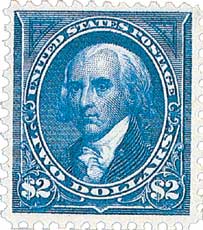

# 262 - 1894 $2 Madison, unwatermarked

1894 $2 Madison

Type II

Issue Quantity: 10,027

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Blue

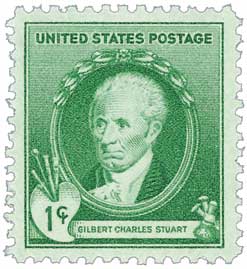

Birth Of Artist Gilbert Stuart

Stuart was the third child of Gilbert Stuart, who worked in America’s first colonial snuff mill. When he was six, Stuart’s family moved to Newport, Rhode Island. It was there that he first began to show an interest and talent for painting. In 1770, Stuart met Scottish artist Cosmo Alexander, who served as his first art tutor. The following year Stuart traveled to Scotland with Alexander but returned to America in 1773 following his tutor’s death.

Stuart didn’t remain in America for long. After the Revolutionary War started, he departed for Europe to study, as John Singleton Copley had done before him. While he struggled at first, Stuart eventually met artist Benjamin West, under whom he studied for the next six years. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1777 and found his first real success with The Skater in 1782, his first full-length portrait. Stuart recalled that he was “suddenly lifted into fame by a single picture.”

In all, Stuart spent about 18 years in Britain and Ireland, earning some of the highest commissions of the day. He finally returned to America in 1793, first living in New York City before settling in Germantown, Pennsylvania, two years later. There, he established a studio and was soon hired to paint some of the most famous and significant Americans of the day.

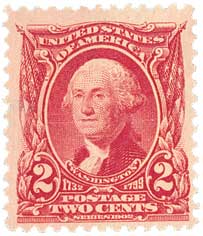

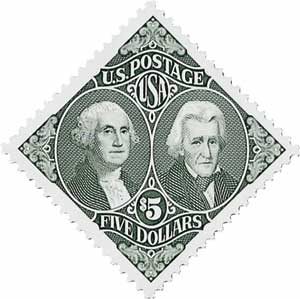

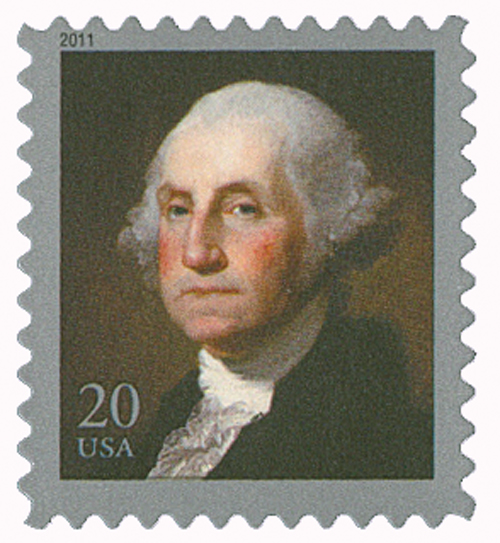

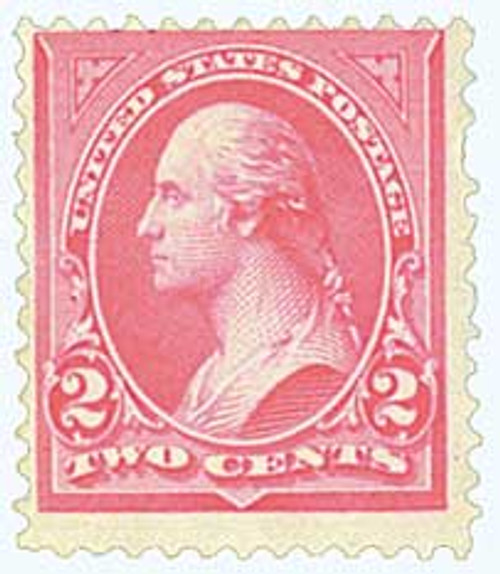

One of Stuart’s goals in moving to Germantown (near then-US capital Philadelphia) was getting to paint President George Washington. He succeeded and had the first of several sittings with the president in March of 1795. From these sittings, Stuart produced some of his most famous paintings, notably The Athenaeum, which was later used for the $1 bill and several US stamps. During his lifetime, Stuart and his daughters painted 130 reproductions of The Athenaeum, but he never finished the original. Another famous Washington painting is the Lansdowne portrait, which was famously saved by Dolley Madison during the War of 1812.

After opening a studio in Washington DC, Stuart moved to Boston in 1805. There he exhibited his works and continued to paint. Many other artists also sought him out for advice, including John Trumbull, Thomas Sully, and John Vanderlyn.

Over the course of his career, Stuart painted more than 1,000 people, including the first six presidents. He was in high demand, not only for his painting talent but for his demeanor during sittings. As John Adams later described, “Speaking generally, no penance is like having one’s picture done. You must sit in a constrained and unnatural position, which is a trial to the temper. But I should like to sit to Stuart from the first of January to the last of December, for he lets me do just what I please, and keeps me constantly amused by his conversation.”

Stuart suffered a stroke in 1824 that left him partially paralyzed. In spite of this, he continued to paint for the next two years until his death on July 9, 1828. Unfortunately, Stuart was never good with money and when he died was in deep debt. His family was unable to purchase him a gravesite, so he was buried in an unmarked grave in the Old South Burial Ground of Boston Common. A decade later his family recovered from their debt and wanted to move his body to their family plot, but couldn’t remember exactly where he was buried, so he was never moved.

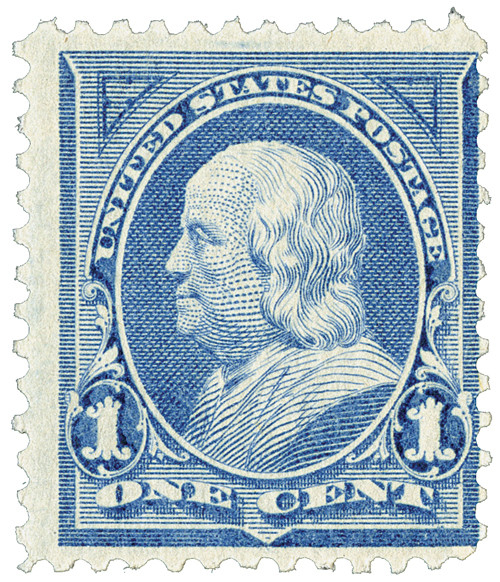

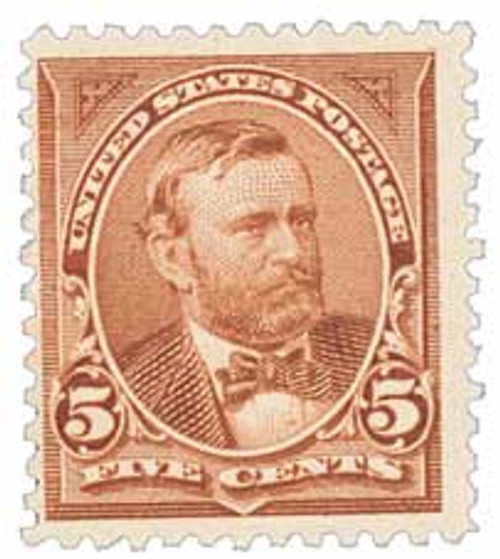

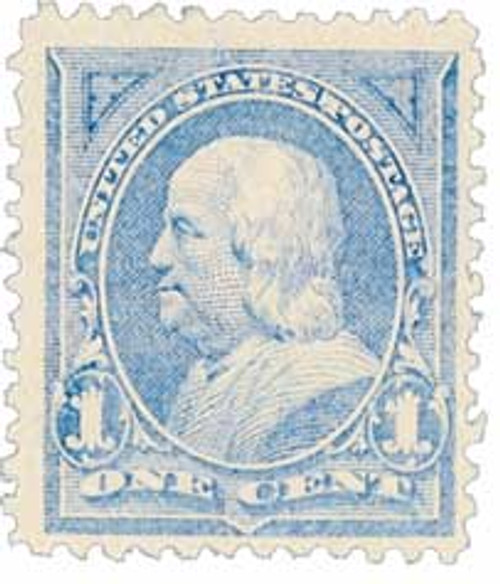

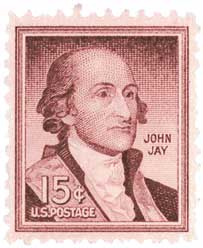

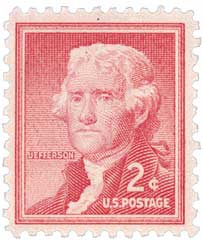

Over the years, Stuart’s paintings have served as the models for a number of US stamps, including these:

Click here to see more Stuart paintings.

1894 $2 Madison

Type II

Issue Quantity: 10,027

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Blue

Birth Of Artist Gilbert Stuart

Stuart was the third child of Gilbert Stuart, who worked in America’s first colonial snuff mill. When he was six, Stuart’s family moved to Newport, Rhode Island. It was there that he first began to show an interest and talent for painting. In 1770, Stuart met Scottish artist Cosmo Alexander, who served as his first art tutor. The following year Stuart traveled to Scotland with Alexander but returned to America in 1773 following his tutor’s death.

Stuart didn’t remain in America for long. After the Revolutionary War started, he departed for Europe to study, as John Singleton Copley had done before him. While he struggled at first, Stuart eventually met artist Benjamin West, under whom he studied for the next six years. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1777 and found his first real success with The Skater in 1782, his first full-length portrait. Stuart recalled that he was “suddenly lifted into fame by a single picture.”

In all, Stuart spent about 18 years in Britain and Ireland, earning some of the highest commissions of the day. He finally returned to America in 1793, first living in New York City before settling in Germantown, Pennsylvania, two years later. There, he established a studio and was soon hired to paint some of the most famous and significant Americans of the day.

One of Stuart’s goals in moving to Germantown (near then-US capital Philadelphia) was getting to paint President George Washington. He succeeded and had the first of several sittings with the president in March of 1795. From these sittings, Stuart produced some of his most famous paintings, notably The Athenaeum, which was later used for the $1 bill and several US stamps. During his lifetime, Stuart and his daughters painted 130 reproductions of The Athenaeum, but he never finished the original. Another famous Washington painting is the Lansdowne portrait, which was famously saved by Dolley Madison during the War of 1812.

After opening a studio in Washington DC, Stuart moved to Boston in 1805. There he exhibited his works and continued to paint. Many other artists also sought him out for advice, including John Trumbull, Thomas Sully, and John Vanderlyn.

Over the course of his career, Stuart painted more than 1,000 people, including the first six presidents. He was in high demand, not only for his painting talent but for his demeanor during sittings. As John Adams later described, “Speaking generally, no penance is like having one’s picture done. You must sit in a constrained and unnatural position, which is a trial to the temper. But I should like to sit to Stuart from the first of January to the last of December, for he lets me do just what I please, and keeps me constantly amused by his conversation.”

Stuart suffered a stroke in 1824 that left him partially paralyzed. In spite of this, he continued to paint for the next two years until his death on July 9, 1828. Unfortunately, Stuart was never good with money and when he died was in deep debt. His family was unable to purchase him a gravesite, so he was buried in an unmarked grave in the Old South Burial Ground of Boston Common. A decade later his family recovered from their debt and wanted to move his body to their family plot, but couldn’t remember exactly where he was buried, so he was never moved.

Over the years, Stuart’s paintings have served as the models for a number of US stamps, including these:

Click here to see more Stuart paintings.