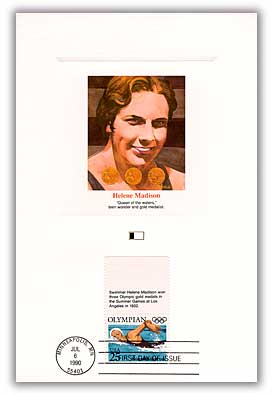

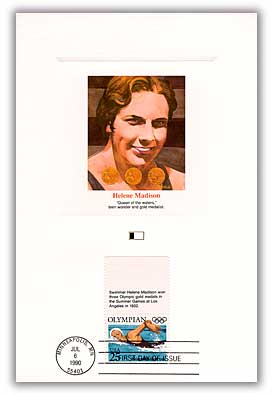

# 2500 FDC - 1990 25c Olympians: Helene Madison

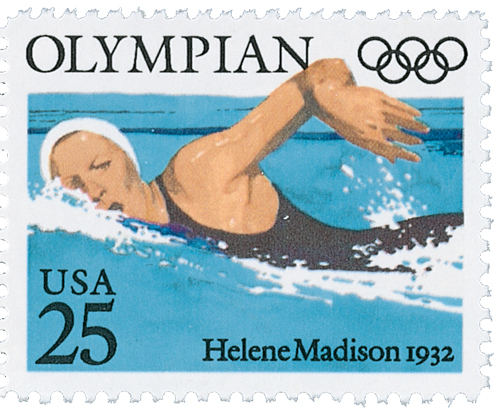

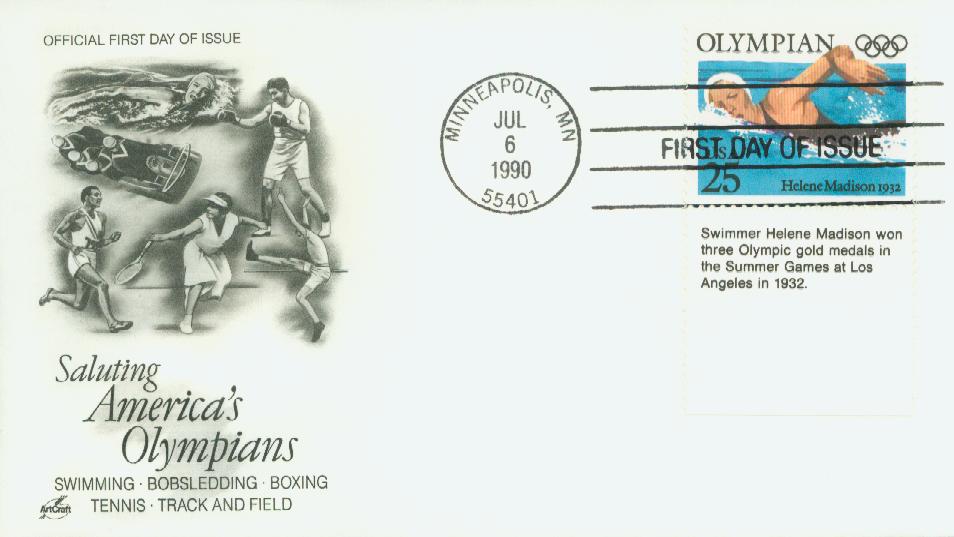

25¢ Helene Madison

City: Minneapolis, Minnesota

Quantity: 35,717,500

Printed By: American Bank Note Co

Printing Method: Photogravure

Perforations: 11

Color: Multicolored

Birth of Helene Madison

Madison’s family moved to Seattle, Washington when she was two. As a child, she loved swimming in Green Lake. She played other sports in school, but always liked swimming the best.

Jack Torney provided Madison with some of her early swimming training, helping her to improve her technique. By the time she was a teenager, she outswam all the other swimmers at Green Lake. Another coach, Ray Daughters, had seen Madison’s success in summer league competitions and offered her further training.

When she was 15, Madison broke the state record for the women’s 100-yard freestyle. Not long after, she broke the Pacific Coast record. Madison made her national debut the following year and broke six records in one swim at the national championships in Florida. Madison continued to break records over the next two years and became the first woman to swim the 100-yard freestyle in one minute.

In 1931, the Associated Press named Madison their female athlete of the year. That year and the following year, she won every freestyle event at the US Women’s Nationals. And in 1932, she qualified for the summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

In her first race at the 1932 summer Olympics, Madison won the women’s 100-meter freestyle with a time that was four seconds faster than the Olympic record. She then won her second gold medal in the 400-meter relay, with her team breaking the previous world record by 9.6 seconds. Madison won a third gold medal the following day in the 400-meter freestyle, a race that many consider to be the one of the most exciting in Olympic history.

“Queen Helene,” as she came to be known, returned home to Seattle and received one of the city’s largest-ever ticker-tape parades. After much celebration and a swimming demonstration, Helene went to Hollywood to pursue an acting career. She only appeared in a few movies – The Human Fish (1932), It’s Great to Be Alive (1933) and The Warrior’s Husband (1933) – but didn’t find much success as an actress.

Madison returned to Seattle and hoped to find work as a swimming instructor, but the city’s parks department didn’t allow women to teach swimming, even with her three gold medals. Instead, she found work at a concession stand and a department store. In 1948, she opened a swimming school at the Moore Hotel, but closed it in the late 1950s after suffering two minor strokes and undergoing back surgery. She went on to work part-time in a convalescent home and was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1966. She died four years later on November 27, 1970.

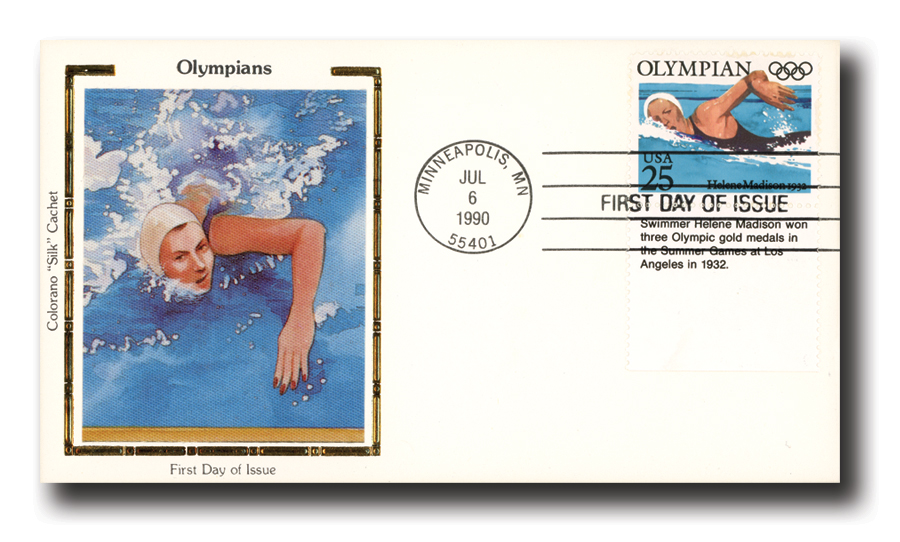

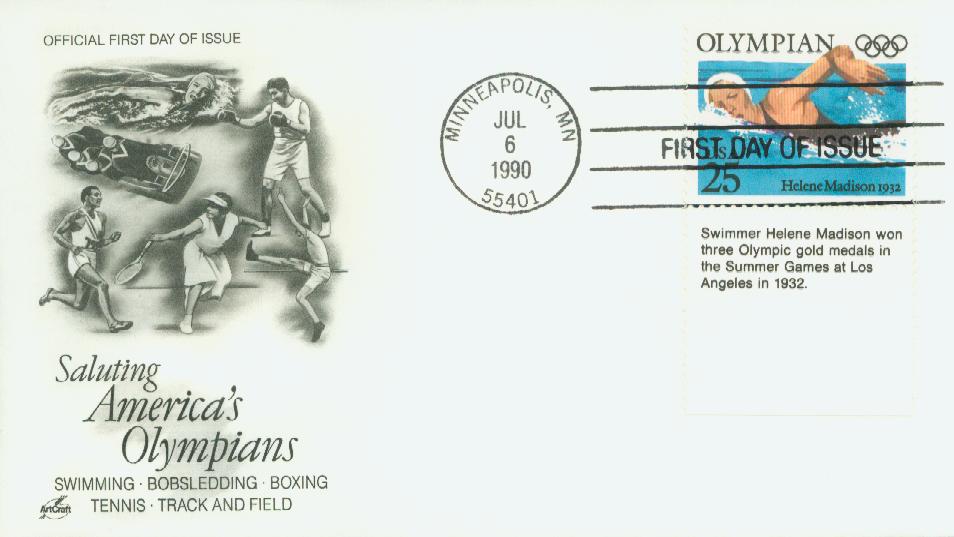

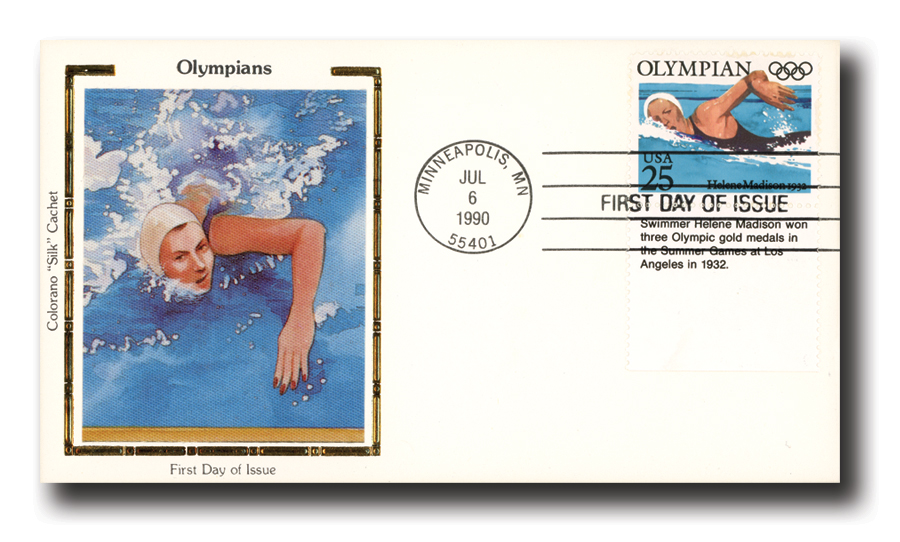

25¢ Helene Madison

City: Minneapolis, Minnesota

Quantity: 35,717,500

Printed By: American Bank Note Co

Printing Method: Photogravure

Perforations: 11

Color: Multicolored

Birth of Helene Madison

Madison’s family moved to Seattle, Washington when she was two. As a child, she loved swimming in Green Lake. She played other sports in school, but always liked swimming the best.

Jack Torney provided Madison with some of her early swimming training, helping her to improve her technique. By the time she was a teenager, she outswam all the other swimmers at Green Lake. Another coach, Ray Daughters, had seen Madison’s success in summer league competitions and offered her further training.

When she was 15, Madison broke the state record for the women’s 100-yard freestyle. Not long after, she broke the Pacific Coast record. Madison made her national debut the following year and broke six records in one swim at the national championships in Florida. Madison continued to break records over the next two years and became the first woman to swim the 100-yard freestyle in one minute.

In 1931, the Associated Press named Madison their female athlete of the year. That year and the following year, she won every freestyle event at the US Women’s Nationals. And in 1932, she qualified for the summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

In her first race at the 1932 summer Olympics, Madison won the women’s 100-meter freestyle with a time that was four seconds faster than the Olympic record. She then won her second gold medal in the 400-meter relay, with her team breaking the previous world record by 9.6 seconds. Madison won a third gold medal the following day in the 400-meter freestyle, a race that many consider to be the one of the most exciting in Olympic history.

“Queen Helene,” as she came to be known, returned home to Seattle and received one of the city’s largest-ever ticker-tape parades. After much celebration and a swimming demonstration, Helene went to Hollywood to pursue an acting career. She only appeared in a few movies – The Human Fish (1932), It’s Great to Be Alive (1933) and The Warrior’s Husband (1933) – but didn’t find much success as an actress.

Madison returned to Seattle and hoped to find work as a swimming instructor, but the city’s parks department didn’t allow women to teach swimming, even with her three gold medals. Instead, she found work at a concession stand and a department store. In 1948, she opened a swimming school at the Moore Hotel, but closed it in the late 1950s after suffering two minor strokes and undergoing back surgery. She went on to work part-time in a convalescent home and was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1966. She died four years later on November 27, 1970.