# 2437 - 1989 25c Traditional Mail Delivery: Automobile

U.S. #2437

1989 25¢ Automobile

Traditional Mail Delivery

- Issued for the 20th Universal Postal Union, first in the US in 92 years

- Stamp design pictures a Jenny bi-plane

- Also issued as part of World Stamp Expo ’89

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Traditional Mail Delivery

Value: 25¢, first-class mail rate

First Day of Issue: November 19, 1989

First Day City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity Issued: 40,956,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Lithographed & engraved

Format: Panes of 40 in sheets of 160

Perforations: 11

Why the stamp was issued: The block of four Traditional Mail Delivery stamps was issued to commemorate the United States’ hosting of 20th Universal Postal Union Congress. It was the first time the US hosted the UPU in 92 years. The stamp issue, and the congress, also coincided with World Stamp Expo ’89. A souvenir sheet bearing the same designs (#2438) was issued nine days later.

About the stamp design: First-time stamp artist Mark Hess was hired to illustrate the Classic Mail Transportation Block. He worked from a variety of sources, including photos from the National Philatelic Collection at the Smithsonian. After completing his first drafts, he shared them with the curator of the National Philatelic Collection, who offered several suggestions to help make his designs more accurate.

Hess based his image of an automobile delivering mail on a photo from the USPS archives. It pictures a 1906 Columbia automobile on the streets of Baltimore.

Special design details: Some of the transportation methods in this block had appeared on stamps before. The Jenny had appeared on America’s first Airmails (#C1-3), and the Jenny and the stagecoach were included in a block of four stamps honoring the 200th anniversary of America’s independent postal service (#1572-75). Plus, the automobile is very similar to the one pictured on a 1912 15¢ Parcel Post stamp (#Q7).

First Day City: The First Day Ceremony for the Classic Mail Transportation block was held the Washington Convention Center in Washington, DC, as part of the 20th Universal Postal Union Congress and World Stamp Expo ’89. Each day of the expo had a theme, and this day’s theme was Old West Day. An actor portraying Buffalo Bill Cody participated in the ceremony.

Unusual fact about this stamp: Errors with the dark blue engraving (USA and 25) have been found.

About the Traditional Mail Delivery Stamps: Early on, USPS officials decided that the stamps honoring the UPU Congress would feature mail delivery methods. Initially, art director Richard Sheaff mocked up a block of nine stamps showing delivery methods from around the world. After significant discussion, they decided that the stamps would only picture US mail delivery methods. They also decided to create two separate blocks depicting past delivery methods and future delivery methods (block of four – #C122-25 and souvenir sheet – #C126).

The other stamps in the set picture:

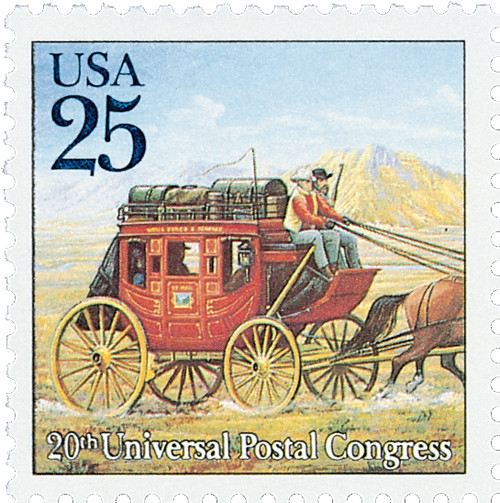

Stagecoach (#2434) – Hess’ stagecoach image underwent the fewest changes. It depicts a Concord coach, named for the city in New Hampshire where they were made.

Steamboat (#2435) – The design that required the most work was the ship stamp. Initially, Hess pictured a naval ship off-shore with a rowboat collecting mail for delivery to the ship. The image had some inaccuracies, and it was ultimately decided that a steamboat on an inland river better represented that form of mail delivery. The steamboat on which the stamp image was based is the 19th century packet Chesapeake. The stamp also shows a man with a handcart bringing mail to the boat, which he had seen on one the Smithsonian pictures.

Curtiss JN-4H (Jenny) bi-plane (#2436) – Hess’ original sketch of the Curtiss Jenny showed two open cockpits. But he corrected it to show that one of the cockpits had been replaced with a mail compartment.

About the Universal Postal Union: On October 9, 1874, some 22 nations met in Bern, Switzerland to form the General Postal Union (later renamed the Universal Postal Union or UPU).

In 1863, Abraham Lincoln’s Postmaster General Montgomery Blair suggested an international conference be held to discuss common postal problems. A conference was held in Paris, and fifteen nations attempted to establish guidelines for an international postal service. Until this time, mail had been regulated by a number of different agreements that were binding only to signing members.

Although Blair did not intend to create a permanent organization, another conference was held 11 years later in Bern, Switzerland. On October 9, 1874, twenty-two nations, comprising the International Postal congress, drafted and signed the Bern Treaty, which established the General Postal Union. The basic ideals were that there should be a uniform rate to mail a letter anywhere in the world, that domestic and international mail should be treated equally, and that each country should keep all money collected for international postage. It also made sending international mail easier in another important way. Previously, people had to attach a stamp from each country their mail would pass through. This no longer was necessary.

Under this treaty, member nations, including parts of Europe, Britain, and the United States, standardized postal rates and units of weight. They also set forth procedures for transporting ordinary mail. Ordinary mail included letters, postcards, and small packages. Separate rules govern the transportation of items, such as parcel post, newspapers, magazines, and money orders.

Under this agreement, known as the International Postal Convention, a simpler accounting system was devised as well. Previously, countries could vary the international rate. Any mail traveling across a country’s border was charged this rate. In addition, many countries charged a one-cent surtax for mail being transported by sea for more than 300 miles.

Using the basic idea that every letter generates a reply, the Convention allowed each country to keep the postage it collected on international mail. However, that country would then reimburse other members for transporting mail across their borders. The benefits to member nations included lower postal rates, better service, and a more efficient accounting system.

At the 1878 conference, the name was changed to the Universal Postal Union. It wasn’t until the 1880s that the organization became truly universal. By the 1890s, nearly every nation had become a member.

In 1898, the Universal Postal Union standardized the colors of certain stamps in order to make international mailing easier and more efficient. They proposed that member nations use the same colors for stamps of the same value. In order to conform to the UPU’s regulations, the 1¢, 2¢, and 5¢ stamps underwent color changes. Later that same year, the 4¢, 6¢, 10¢, and 15¢ stamps were changed to avoid confusion with current issues printed in similar colors.

In 1947, the UPU became a specialized agency of the United Nations with its headquarters is located in Berne, the capital of Switzerland. The UPU holds conventions every five years. Today, it continues to organize and improve postal service throughout the world with 190 member states. It’s the oldest international organization existing and claims to be the only one that really works.

History this stamp represents: On March 9, 1858, iron manufacturer Albert Potts of Philadelphia patented an early mail collection box.

Letter boxes were used in New York City as early as 1833 to coincide with the penny post. These boxes were placed along delivery routes and carriers collected the mail Monday thru Saturday at 1:00 p.m. They charged a fee of two cents per item to transport these letters to the post office. These boxes only remained in use for a few years before being removed.

Private letter delivery companies also provided collection boxes in larger cities. In New York, the Post Office Department purchased the City Despatch Post in 1842 and had 112 collecting stations at convenient locations throughout the city. However, that service only lasted until 1846, leaving mailers without a convenient place to send out their mail.

Other cities used letter boxes at various times. Collection boxes were installed in Jersey City, New Jersey in 1848 and in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1851. The Post Office once again began using letter boxes in New York City in 1852. There were hundreds of boxes throughout the city by 1855, with carriers collecting mail four times a day. However, some, such as postal reformer Pliny Miles, complained that the system wasn’t effective – “1,000 little tin boxes in as many places of business in New York” that could only be used when the businesses were open. Plus, the boxes were small and had no locks, so anyone could remove the mail, or even walk away with the entire box!

In Philadelphia, iron manufacturer Albert Potts developed his own solution. On March 9, 1858, he received a patent for a “new and improved combination of Letter-Box and Lamp-Post for municipalities.” Potts’s patent described in detail how to attach the post boxes to his lamp posts. He said that these new boxes would make it easier and safer for people to drop off their mail at any time of day. And that people visiting the city could easily identify the mailboxes. While his letter boxes were put into use by the Post Office Department, cities didn’t purchase his lamp posts to go along with them, as he had hoped. By 1859, more than 300 of Potts’s mailboxes were installed on Philadelphia lamp posts “bringing the Post Office to everyone’s door.”

Other cities continued to test their own letter boxes. On August 2, 1858, Boston postmaster Nahum Capen installed 33 secure iron boxes on the city’s busiest street corners. New York City started using lamp post mail boxes in November 1859 and by November 1860, had 574 cast-iron boxes around the city, with mail collections four times a day.

The US Post Office inaugurated free home delivery in cities in 1863 and also called for the placement of tin or wood boxes at convenient locations throughout the city where mail could be dropped off. In 1869, Samuel Strong became the first known person to receive a letter box contract from the Post Office, for his Flat-Top Box. While he claimed it was secure and easy to empty, mail carriers disagreed. The Post Office considered a variety of new designs, ultimately deciding on the round-top box. By the 1880s, they had purchased more than 35,000 round-top mailboxes in two sizes. This design wasn’t without its flaws. Though simple to use, the letter slot could let in rain or snow, and thieves could figure out a way to steal the mail. Plus, cities used a few different types of letter boxes, which created some confusion, with stories arising of people placing their mail in fire hydrants and alarm boxes.

In 1889, Willard D. Doremus patented a new, more secure design. However, most people were used to the mail going into a slot on the side and were unsure where to deposit their letters in his mailbox. The Post Office spent several years trying to develop the perfect mailboxes. In 1911 they began testing drop-bottom mailboxes, which made mail collection much quicker – letting gravity do the work for mail carriers.

Larger mailboxes had been in limited use since the 1880s. Letter boxes couldn’t fit newspapers or packages and people often left these items on top of the mailbox, where weather and thieves could carry them away. With the introduction of Parcel Post in 1913, the need for larger collection boxes increased and most smaller boxes were replaced. While the Post Office has experimented with variations such as foot pedals and snorkel shoots, the overall design has remained much the same since the early 1900s. Mailbox colors changed over the years – green and red were common in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In the 1950s, they were made red, white, and blue, and since 1970, have remained dark blue.

U.S. #2437

1989 25¢ Automobile

Traditional Mail Delivery

- Issued for the 20th Universal Postal Union, first in the US in 92 years

- Stamp design pictures a Jenny bi-plane

- Also issued as part of World Stamp Expo ’89

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Traditional Mail Delivery

Value: 25¢, first-class mail rate

First Day of Issue: November 19, 1989

First Day City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity Issued: 40,956,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Lithographed & engraved

Format: Panes of 40 in sheets of 160

Perforations: 11

Why the stamp was issued: The block of four Traditional Mail Delivery stamps was issued to commemorate the United States’ hosting of 20th Universal Postal Union Congress. It was the first time the US hosted the UPU in 92 years. The stamp issue, and the congress, also coincided with World Stamp Expo ’89. A souvenir sheet bearing the same designs (#2438) was issued nine days later.

About the stamp design: First-time stamp artist Mark Hess was hired to illustrate the Classic Mail Transportation Block. He worked from a variety of sources, including photos from the National Philatelic Collection at the Smithsonian. After completing his first drafts, he shared them with the curator of the National Philatelic Collection, who offered several suggestions to help make his designs more accurate.

Hess based his image of an automobile delivering mail on a photo from the USPS archives. It pictures a 1906 Columbia automobile on the streets of Baltimore.

Special design details: Some of the transportation methods in this block had appeared on stamps before. The Jenny had appeared on America’s first Airmails (#C1-3), and the Jenny and the stagecoach were included in a block of four stamps honoring the 200th anniversary of America’s independent postal service (#1572-75). Plus, the automobile is very similar to the one pictured on a 1912 15¢ Parcel Post stamp (#Q7).

First Day City: The First Day Ceremony for the Classic Mail Transportation block was held the Washington Convention Center in Washington, DC, as part of the 20th Universal Postal Union Congress and World Stamp Expo ’89. Each day of the expo had a theme, and this day’s theme was Old West Day. An actor portraying Buffalo Bill Cody participated in the ceremony.

Unusual fact about this stamp: Errors with the dark blue engraving (USA and 25) have been found.

About the Traditional Mail Delivery Stamps: Early on, USPS officials decided that the stamps honoring the UPU Congress would feature mail delivery methods. Initially, art director Richard Sheaff mocked up a block of nine stamps showing delivery methods from around the world. After significant discussion, they decided that the stamps would only picture US mail delivery methods. They also decided to create two separate blocks depicting past delivery methods and future delivery methods (block of four – #C122-25 and souvenir sheet – #C126).

The other stamps in the set picture:

Stagecoach (#2434) – Hess’ stagecoach image underwent the fewest changes. It depicts a Concord coach, named for the city in New Hampshire where they were made.

Steamboat (#2435) – The design that required the most work was the ship stamp. Initially, Hess pictured a naval ship off-shore with a rowboat collecting mail for delivery to the ship. The image had some inaccuracies, and it was ultimately decided that a steamboat on an inland river better represented that form of mail delivery. The steamboat on which the stamp image was based is the 19th century packet Chesapeake. The stamp also shows a man with a handcart bringing mail to the boat, which he had seen on one the Smithsonian pictures.

Curtiss JN-4H (Jenny) bi-plane (#2436) – Hess’ original sketch of the Curtiss Jenny showed two open cockpits. But he corrected it to show that one of the cockpits had been replaced with a mail compartment.

About the Universal Postal Union: On October 9, 1874, some 22 nations met in Bern, Switzerland to form the General Postal Union (later renamed the Universal Postal Union or UPU).

In 1863, Abraham Lincoln’s Postmaster General Montgomery Blair suggested an international conference be held to discuss common postal problems. A conference was held in Paris, and fifteen nations attempted to establish guidelines for an international postal service. Until this time, mail had been regulated by a number of different agreements that were binding only to signing members.

Although Blair did not intend to create a permanent organization, another conference was held 11 years later in Bern, Switzerland. On October 9, 1874, twenty-two nations, comprising the International Postal congress, drafted and signed the Bern Treaty, which established the General Postal Union. The basic ideals were that there should be a uniform rate to mail a letter anywhere in the world, that domestic and international mail should be treated equally, and that each country should keep all money collected for international postage. It also made sending international mail easier in another important way. Previously, people had to attach a stamp from each country their mail would pass through. This no longer was necessary.

Under this treaty, member nations, including parts of Europe, Britain, and the United States, standardized postal rates and units of weight. They also set forth procedures for transporting ordinary mail. Ordinary mail included letters, postcards, and small packages. Separate rules govern the transportation of items, such as parcel post, newspapers, magazines, and money orders.

Under this agreement, known as the International Postal Convention, a simpler accounting system was devised as well. Previously, countries could vary the international rate. Any mail traveling across a country’s border was charged this rate. In addition, many countries charged a one-cent surtax for mail being transported by sea for more than 300 miles.

Using the basic idea that every letter generates a reply, the Convention allowed each country to keep the postage it collected on international mail. However, that country would then reimburse other members for transporting mail across their borders. The benefits to member nations included lower postal rates, better service, and a more efficient accounting system.

At the 1878 conference, the name was changed to the Universal Postal Union. It wasn’t until the 1880s that the organization became truly universal. By the 1890s, nearly every nation had become a member.

In 1898, the Universal Postal Union standardized the colors of certain stamps in order to make international mailing easier and more efficient. They proposed that member nations use the same colors for stamps of the same value. In order to conform to the UPU’s regulations, the 1¢, 2¢, and 5¢ stamps underwent color changes. Later that same year, the 4¢, 6¢, 10¢, and 15¢ stamps were changed to avoid confusion with current issues printed in similar colors.

In 1947, the UPU became a specialized agency of the United Nations with its headquarters is located in Berne, the capital of Switzerland. The UPU holds conventions every five years. Today, it continues to organize and improve postal service throughout the world with 190 member states. It’s the oldest international organization existing and claims to be the only one that really works.

History this stamp represents: On March 9, 1858, iron manufacturer Albert Potts of Philadelphia patented an early mail collection box.

Letter boxes were used in New York City as early as 1833 to coincide with the penny post. These boxes were placed along delivery routes and carriers collected the mail Monday thru Saturday at 1:00 p.m. They charged a fee of two cents per item to transport these letters to the post office. These boxes only remained in use for a few years before being removed.

Private letter delivery companies also provided collection boxes in larger cities. In New York, the Post Office Department purchased the City Despatch Post in 1842 and had 112 collecting stations at convenient locations throughout the city. However, that service only lasted until 1846, leaving mailers without a convenient place to send out their mail.

Other cities used letter boxes at various times. Collection boxes were installed in Jersey City, New Jersey in 1848 and in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1851. The Post Office once again began using letter boxes in New York City in 1852. There were hundreds of boxes throughout the city by 1855, with carriers collecting mail four times a day. However, some, such as postal reformer Pliny Miles, complained that the system wasn’t effective – “1,000 little tin boxes in as many places of business in New York” that could only be used when the businesses were open. Plus, the boxes were small and had no locks, so anyone could remove the mail, or even walk away with the entire box!

In Philadelphia, iron manufacturer Albert Potts developed his own solution. On March 9, 1858, he received a patent for a “new and improved combination of Letter-Box and Lamp-Post for municipalities.” Potts’s patent described in detail how to attach the post boxes to his lamp posts. He said that these new boxes would make it easier and safer for people to drop off their mail at any time of day. And that people visiting the city could easily identify the mailboxes. While his letter boxes were put into use by the Post Office Department, cities didn’t purchase his lamp posts to go along with them, as he had hoped. By 1859, more than 300 of Potts’s mailboxes were installed on Philadelphia lamp posts “bringing the Post Office to everyone’s door.”

Other cities continued to test their own letter boxes. On August 2, 1858, Boston postmaster Nahum Capen installed 33 secure iron boxes on the city’s busiest street corners. New York City started using lamp post mail boxes in November 1859 and by November 1860, had 574 cast-iron boxes around the city, with mail collections four times a day.

The US Post Office inaugurated free home delivery in cities in 1863 and also called for the placement of tin or wood boxes at convenient locations throughout the city where mail could be dropped off. In 1869, Samuel Strong became the first known person to receive a letter box contract from the Post Office, for his Flat-Top Box. While he claimed it was secure and easy to empty, mail carriers disagreed. The Post Office considered a variety of new designs, ultimately deciding on the round-top box. By the 1880s, they had purchased more than 35,000 round-top mailboxes in two sizes. This design wasn’t without its flaws. Though simple to use, the letter slot could let in rain or snow, and thieves could figure out a way to steal the mail. Plus, cities used a few different types of letter boxes, which created some confusion, with stories arising of people placing their mail in fire hydrants and alarm boxes.

In 1889, Willard D. Doremus patented a new, more secure design. However, most people were used to the mail going into a slot on the side and were unsure where to deposit their letters in his mailbox. The Post Office spent several years trying to develop the perfect mailboxes. In 1911 they began testing drop-bottom mailboxes, which made mail collection much quicker – letting gravity do the work for mail carriers.

Larger mailboxes had been in limited use since the 1880s. Letter boxes couldn’t fit newspapers or packages and people often left these items on top of the mailbox, where weather and thieves could carry them away. With the introduction of Parcel Post in 1913, the need for larger collection boxes increased and most smaller boxes were replaced. While the Post Office has experimented with variations such as foot pedals and snorkel shoots, the overall design has remained much the same since the early 1900s. Mailbox colors changed over the years – green and red were common in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In the 1950s, they were made red, white, and blue, and since 1970, have remained dark blue.