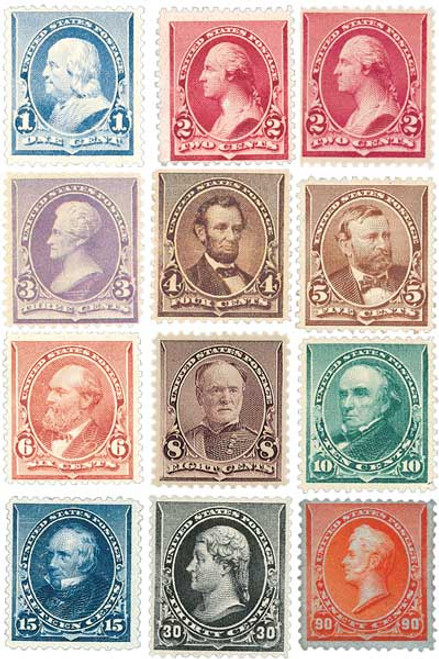

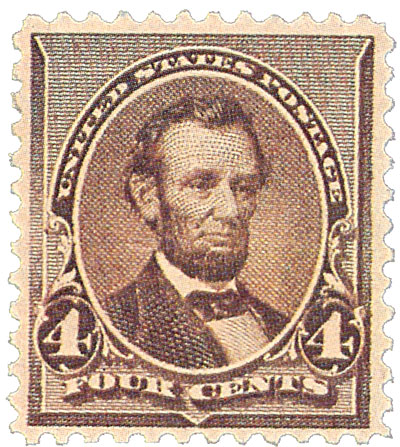

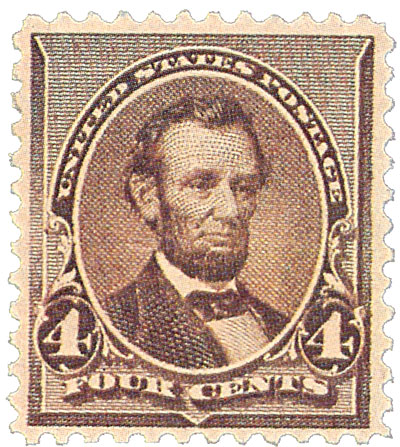

# 222 offer - 1890 4c Lincoln, dark brown

1890-93 Regular Issue 4¢ Lincoln

Issue Date: February 22, 1890

Issue Quantity: 46,877,200

Printed by: American Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Dark brown

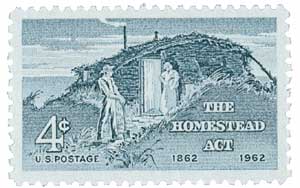

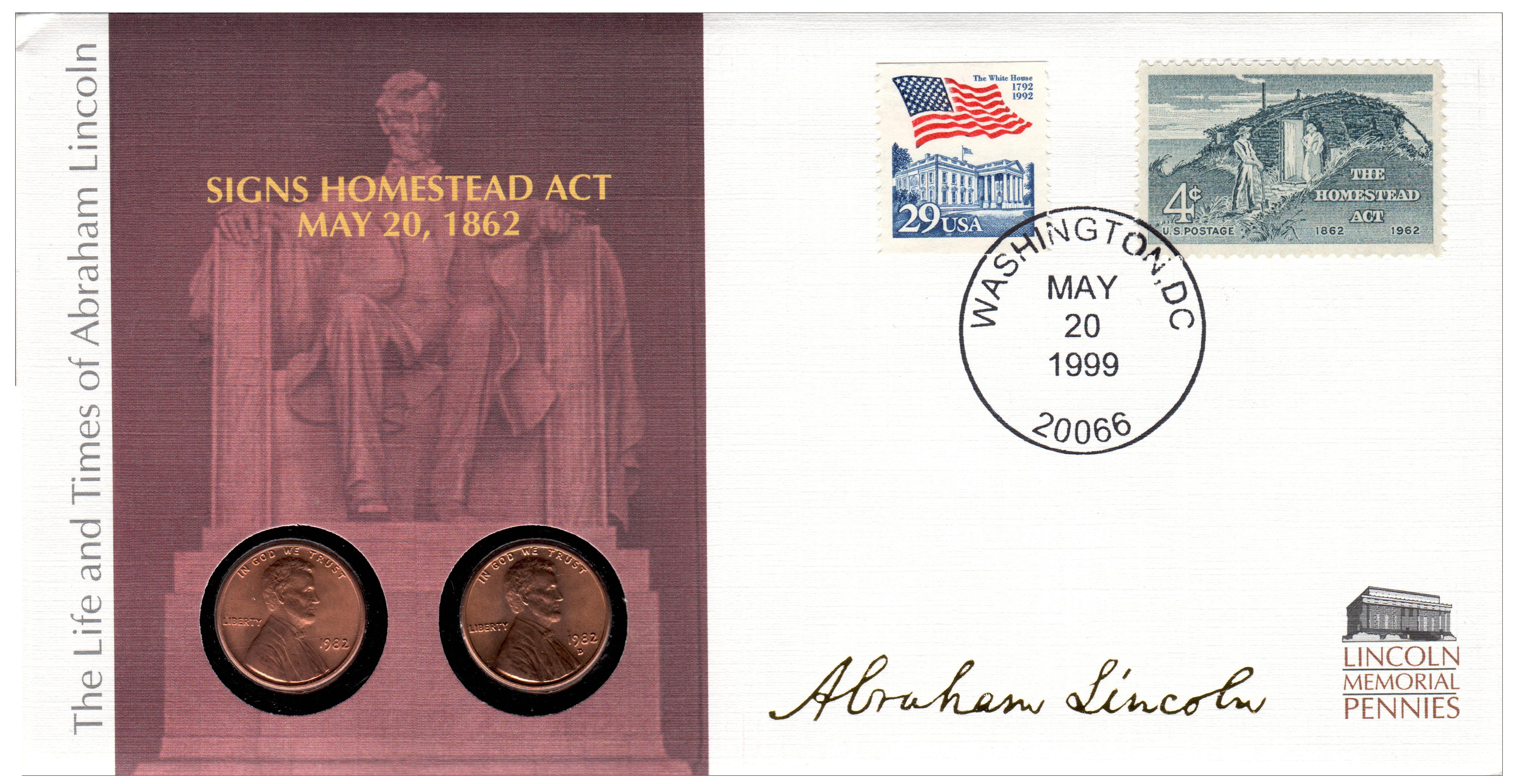

The Homestead Act

Since the American Revolution, the distribution of government lands was a matter of great debate. In America’s early years, setting boundaries on new land was unorganized, causing frequent overlapping claims and disputes. When land ordinance laws were introduced in 1785, the plots were large and pricey. People repeatedly called for cheaper plots or preemption – an arrangement where they would settle first and pay later.

By the 1860s, the debate was still ongoing. Newspaper editor and politician Horace Greeley introduced homestead legislation that was shot down, but used his role at the paper to encourage public support. The Free Soil Party, which eventually became the new Republican party, pushed for a homestead act that would open public lands to independent farmers. The alternative was wealthy planters who would enlist slaves and force smaller farming operations onto meager plots. Every time they proposed such legislation, Southern Democrats shot them down, not wanting the lands to be taken over by immigrants and poor Americans.

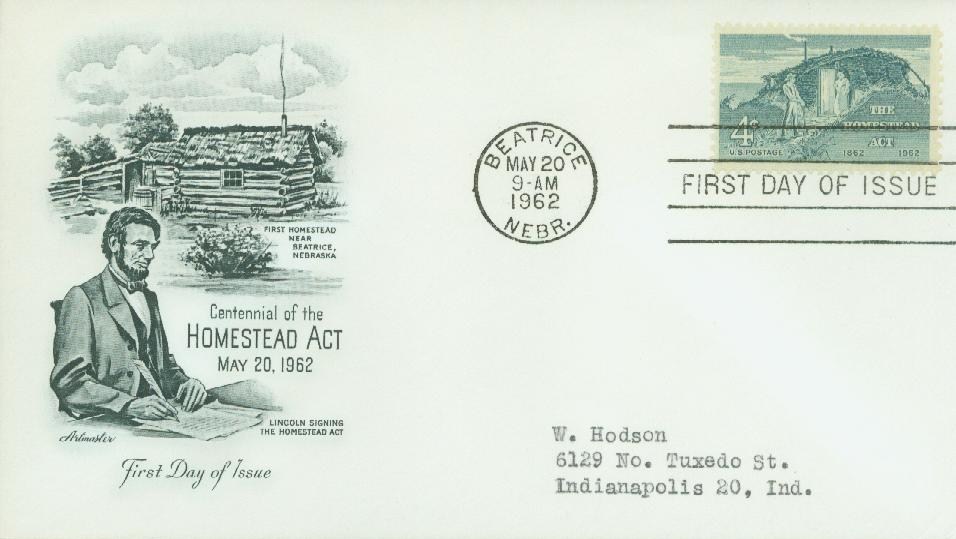

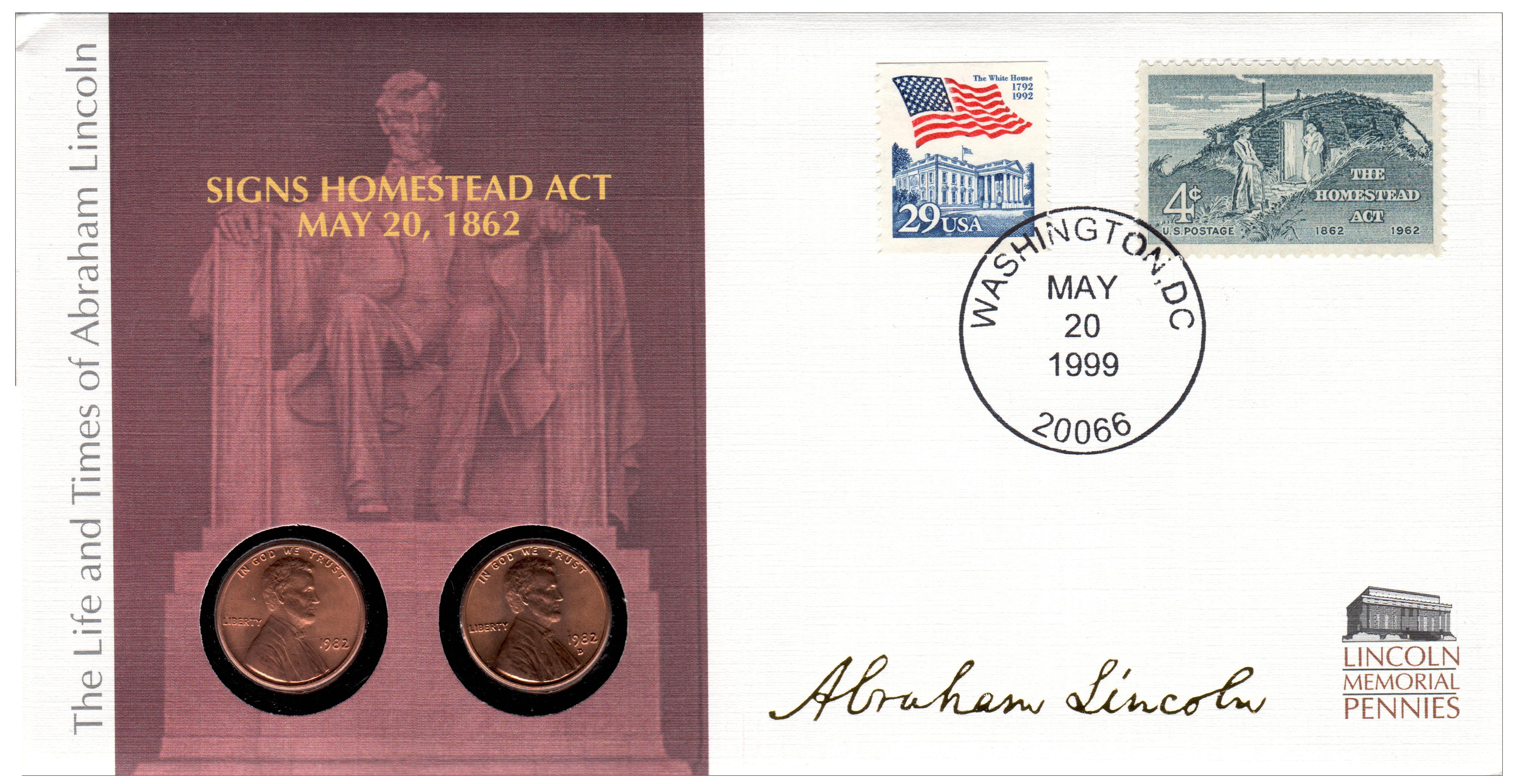

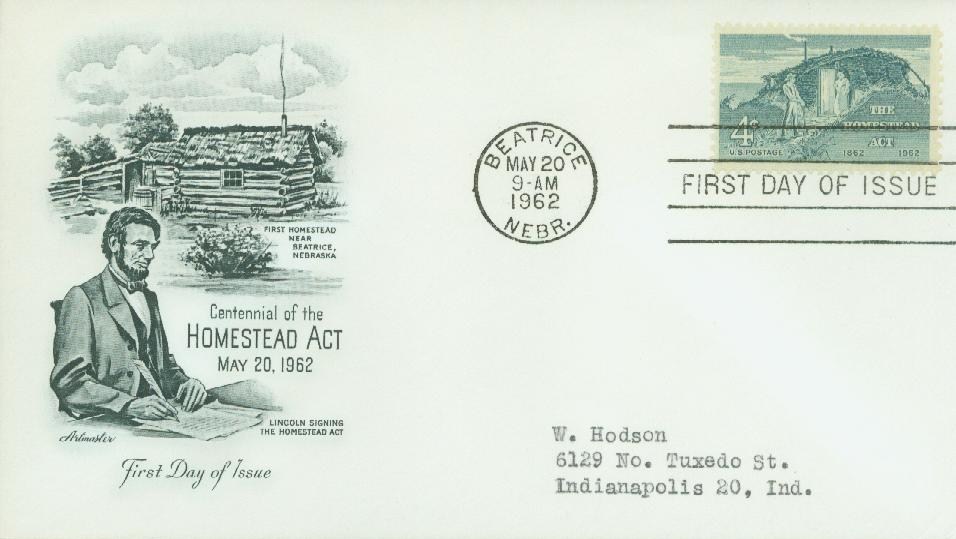

A Homestead Act did manage to pass Congress in 1860, but President James Buchanan vetoed it to appease Southern slave-holders. But when the South seceded from the Union in 1861, their delegates left Congress. Without their opposition the legislation was finally able to pass. President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act into law on May 20, 1862, to become effective on January 1 of the following year.

The Homestead Act opened up millions of acres of land to anyone willing to take it. But there were several provisions that needed to be met in order for them to earn their claim. Homesteaders needed to be the head of a household, at least 21 years old, and pay the $18 filing fee to lay claim to one of the 160-acre parcels of land. Immigrants, women, and former slaves were among those permitted to file for homesteads.

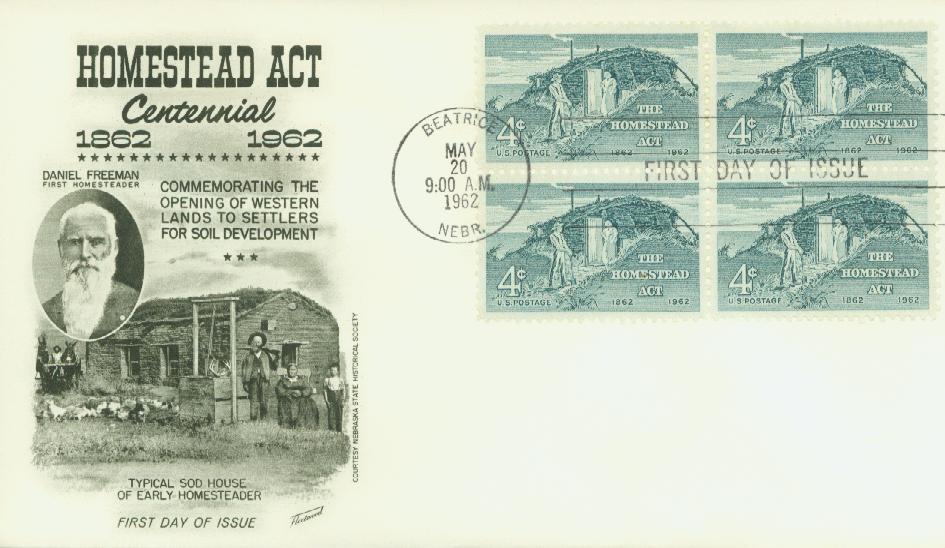

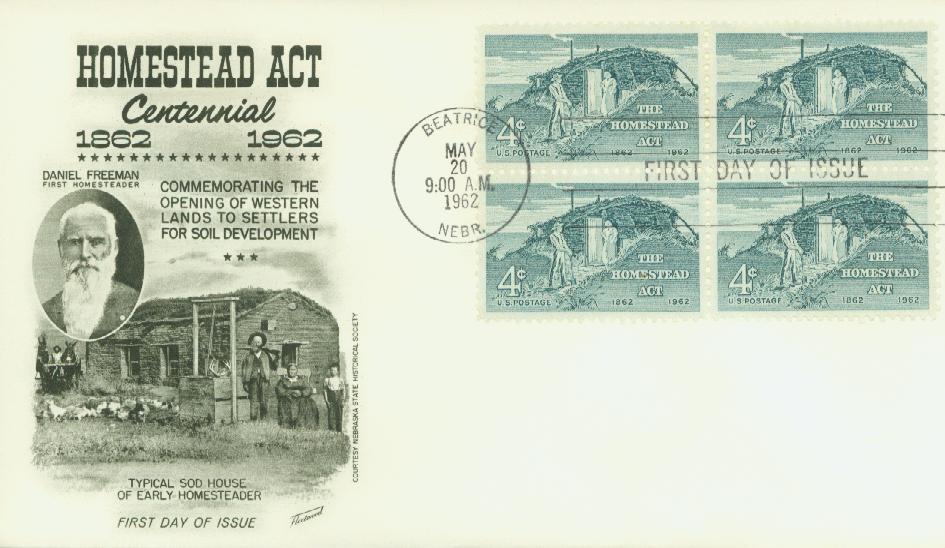

Daniel Freeman, originally of Illinois, filed the first land claim under the Homestead Act. He reportedly filed his claim at the Brownville, Nebraska, land claim office at ten after midnight on January 1, 1863. He later married and raised eight children on his homestead. The Freeman family built a number of structures during their time there. Their log cabin is often considered the first Homestead cabin.

Most new homesteaders, however, built “soddies” as their first homes. Soddies were made with “Nebraska Marble,” as it was called, which was the dense, tangled roots of buffalo grass and the dirt that surrounded it. These bricks held together when cut, and provided a quick and inexpensive way to build a home. Some homesteaders continued to use sod even after lumber was available to them, as it was well-insulated, did not burn, and was tornado-proof. However, soddies needed constant repair – particularly after rain storms, when the roofs would leak dirt, water, and even snakes.

During his lifetime, Daniel Freeman wanted to be recognized as America’s first homesteader. By 1909, other Nebraskans were calling for his land to be preserved as a national park. Little progress was made until Senator George W. Norris joined the campaign. He presented his proposal for the creation of a park in 1935. He succeeded the following year on March 16, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Homestead National Monument Act.

Though the tract of land that encompasses the monument was that of Daniel Freeman, the park is a memorial to the more than two million people who filed claims under the Homestead Act. By the time the act was repealed in 1976, about 783,000 of those people completed the requirements of their claims, settling some 270 to 285 million acres.

Click here to read the Homestead Act.

Click here for more from the National Park Service website.

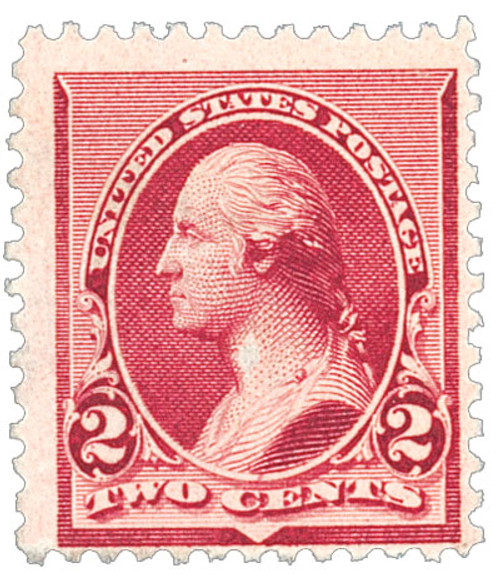

1890-93 Regular Issue 4¢ Lincoln

Issue Date: February 22, 1890

Issue Quantity: 46,877,200

Printed by: American Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Dark brown

The Homestead Act

Since the American Revolution, the distribution of government lands was a matter of great debate. In America’s early years, setting boundaries on new land was unorganized, causing frequent overlapping claims and disputes. When land ordinance laws were introduced in 1785, the plots were large and pricey. People repeatedly called for cheaper plots or preemption – an arrangement where they would settle first and pay later.

By the 1860s, the debate was still ongoing. Newspaper editor and politician Horace Greeley introduced homestead legislation that was shot down, but used his role at the paper to encourage public support. The Free Soil Party, which eventually became the new Republican party, pushed for a homestead act that would open public lands to independent farmers. The alternative was wealthy planters who would enlist slaves and force smaller farming operations onto meager plots. Every time they proposed such legislation, Southern Democrats shot them down, not wanting the lands to be taken over by immigrants and poor Americans.

A Homestead Act did manage to pass Congress in 1860, but President James Buchanan vetoed it to appease Southern slave-holders. But when the South seceded from the Union in 1861, their delegates left Congress. Without their opposition the legislation was finally able to pass. President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act into law on May 20, 1862, to become effective on January 1 of the following year.

The Homestead Act opened up millions of acres of land to anyone willing to take it. But there were several provisions that needed to be met in order for them to earn their claim. Homesteaders needed to be the head of a household, at least 21 years old, and pay the $18 filing fee to lay claim to one of the 160-acre parcels of land. Immigrants, women, and former slaves were among those permitted to file for homesteads.

Daniel Freeman, originally of Illinois, filed the first land claim under the Homestead Act. He reportedly filed his claim at the Brownville, Nebraska, land claim office at ten after midnight on January 1, 1863. He later married and raised eight children on his homestead. The Freeman family built a number of structures during their time there. Their log cabin is often considered the first Homestead cabin.

Most new homesteaders, however, built “soddies” as their first homes. Soddies were made with “Nebraska Marble,” as it was called, which was the dense, tangled roots of buffalo grass and the dirt that surrounded it. These bricks held together when cut, and provided a quick and inexpensive way to build a home. Some homesteaders continued to use sod even after lumber was available to them, as it was well-insulated, did not burn, and was tornado-proof. However, soddies needed constant repair – particularly after rain storms, when the roofs would leak dirt, water, and even snakes.

During his lifetime, Daniel Freeman wanted to be recognized as America’s first homesteader. By 1909, other Nebraskans were calling for his land to be preserved as a national park. Little progress was made until Senator George W. Norris joined the campaign. He presented his proposal for the creation of a park in 1935. He succeeded the following year on March 16, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Homestead National Monument Act.

Though the tract of land that encompasses the monument was that of Daniel Freeman, the park is a memorial to the more than two million people who filed claims under the Homestead Act. By the time the act was repealed in 1976, about 783,000 of those people completed the requirements of their claims, settling some 270 to 285 million acres.

Click here to read the Homestead Act.

Click here for more from the National Park Service website.