U.S. #2046

1983 20¢ George “Babe Ruth” Herman

- Issued on the 50th anniversary of the first All-Star Game

- Honors Babe Ruth, who hit the first All-Star home run

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Value: 20¢, first-class rate

First Day of Issue: July 6, 1983

First Day City: Chicago, Illinois

Quantity Issued: 184,950,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Engraved

Format: Panes of 50 in sheets of 200

Perforations: 10½ x 11

Color: Blue

Why the stamp was issued: To honor one of baseball’s greatest player’s Babe Ruth. Illinois senator and former professional baseball player Scott Lucas had proposed a Babe Ruth stamp in 1948, arguing, “Since it is our custom to make official acknowledgement of our national heroes, I feel such an action should be taken for this man who has become one of America’s immortals.” That proposal was rejected and it would be several decades before the Babe got his stamp.

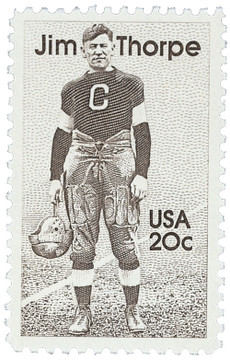

About the stamp design: Retired art director of Sports Illustrated Richard Gangel designed this stamp, using a well-known photo of Ruth with baseball bat in hand. He modified the image somewhat, moving the bat back so it didn’t obscure his face as much. Gangel also widened Ruth’s stance, and added players and some definition of the stadium to the background.

First Day City: The stamp design was initially unveiled on Ruth’s birthday, February 6, at the Babe Ruth Birthplace Foundation headquarters in Baltimore, Maryland. There had been calls for the stamp to be issued in Baltimore, with promises of parades and festivities if that happened, but the USPS intended to issue the stamp in Chicago in connection with the All-Star Game, which was celebrating its 50th anniversary that year. However, the USPS later realized that a ceremony would be lost in the excitement of the All-Star Game. So, they held a special Day ceremony the day before, July 5, during events connected to the Old Timers’ Game. No stamps were available during this ceremony. Then, on July 6, postal booths were set up throughout the stadium. Within each, a single employee stood affixing stamps and canceling First Day Covers. They sold a total of $12,194 in stamps at the stadium that day. But no First Day ceremony was held on that day.

Unusual fact about this stamp: A paper crease variety is known in which the paper folded over during printing, leaving a white diagonal line across the design.

History the stamp represents: George Herman “Babe” Ruth was born on February 6, 1895, in Baltimore, Maryland.

Ruth was reportedly a rambunctious child with a habit of getting into trouble. It’s likely because of this that he was sent to the St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys, where he stayed for 12 years.

Ruth enjoyed playing baseball at a young age. He was left-handed and played as a catcher, third baseman, and shortstop, all of which were unusual at the time for a lefthander to play. His school’s Prefect of Discipline Brother Matthias Boutlier, noticed his talent for baseball and encouraged him to keep playing. Ruth would later estimate that he played about 200 games a year as he worked his way up to the professional teams.

Ruth began his professional baseball career in 1914, joining the Baltimore Orioles minor league team. Ruth quickly established himself as the team’s star pitcher and was also a very successful batter. Despite Ruth’s top performance, the team gained little attention and the coach opted to sell Ruth and his other star players to the Boston Red Sox to help fund his team.

Ruth would play with the Red Sox from 1914 to 1919. During this time, Ruth grew tired of only playing every few games as a pitcher. He wanted to play every day and eventually convinced the coach to move him to the outfield. The move proved wise, as Ruth earned a .300 batting average and helped lead the team to victory in the 1918 World Series.

The following season, Ruth only pitched in 17 of his 130 games and had an 8-5 record. Though the team wouldn’t make it to the World Series, Ruth had a banner year. He became the first major league player to hit a home run in all eight ballparks in his league. And he broke the major league home run record, finishing the season with 29.

During the break between seasons, something unexpected happened. On December 26, 1919, the Boston Red Sox sold Ruth to the New York Yankees. Even now we don’t know all the details that led to the sale of one of baseball’s most recognizable players. In part, it seems the Red Sox owner needed money.

By the time Ruth became a Yankee, he was already considered one of the greatest hitters in the game. He also possessed a flamboyant playing style and became immensely popular with fans and players alike. This was no more evident than in 1923 when the new Yankee Stadium was nicknamed “the House That Ruth Built.” Crowds packed the stadium game after game, to see what great feats Ruth would accomplish that day.

Possibly the most successful season Ruth experienced was 1927, as part of the legendary “Murderer’s Row.” That year, Ruth batted .356 and brought in 164 runs. Also in 1927, he hit 60 home runs, more homers than any other team in the league and a record that would stand for over thirty years.

But it would be the 1929 season that would bring one of Ruth’s greatest accomplishments. By August of that year, he had racked up an unprecedented 499 home runs. Prior to his game at Cleveland’s League Park on August 11, Babe approached the field’s police chief. He told the chief that he would hit his 500th home run that day and wanted to keep the ball.

True to his word, Ruth hit Willis Hudlin’s first pitch in his first at-bat, high over the right-field wall onto Lexington Avenue. As the game continued, the park police rushed to the street to find the lucky fan. Eventually, they found young Jake Geiser and asked for the ball. When his friend suggested that Jake might want to keep the ball, the police and Cleveland team secretary offered to take him to the Yankee dugout to meet Babe. There, Ruth offered Jake a signed ball for the one he’d hit. Jake obliged and Ruth also gave him $20.

Three years later, Ruth had another memorable home run. It occurred during the 1932 World Series at Chicago’s Wrigley Field. Before hitting the ball, he famously reached his arm out, possibly pointing to where he planned to hit the ball. Whether Ruth actually indicated his intentions to the taunting, lemon-throwing Wrigley Field crowd has been widely debated for years. However, it made for good headlines and added to Ruth’s already legendary reputation.

Over the course of his career, Ruth hit 714 home runs, a record that stood until 1974, when Hank Aaron broke it. Barry Bonds was the only other player to hit more than Aaron. Only 26 men have hit more than 500 home runs, but Ruth has the distinction of being the first.

Not only did Ruth set the standard for home runs in nearly every year he played, but he also set many other records, including 2,056 career walks and 72 games in which he hit two or more home runs. He even hit three home runs in a single World Series game twice.

Ruth played with the Yankees until 1934 and played his final season with the Boston Braves. He briefly served as a first base coach, spoke at Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day and attended the opening of the Baseball Hall of Fame. He also made a number of appearances to support the war effort during World War II.

Ruth’s health declined in his later years and he died on August 16, 1948.

U.S. #2046

1983 20¢ George “Babe Ruth” Herman

- Issued on the 50th anniversary of the first All-Star Game

- Honors Babe Ruth, who hit the first All-Star home run

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Value: 20¢, first-class rate

First Day of Issue: July 6, 1983

First Day City: Chicago, Illinois

Quantity Issued: 184,950,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Engraved

Format: Panes of 50 in sheets of 200

Perforations: 10½ x 11

Color: Blue

Why the stamp was issued: To honor one of baseball’s greatest player’s Babe Ruth. Illinois senator and former professional baseball player Scott Lucas had proposed a Babe Ruth stamp in 1948, arguing, “Since it is our custom to make official acknowledgement of our national heroes, I feel such an action should be taken for this man who has become one of America’s immortals.” That proposal was rejected and it would be several decades before the Babe got his stamp.

About the stamp design: Retired art director of Sports Illustrated Richard Gangel designed this stamp, using a well-known photo of Ruth with baseball bat in hand. He modified the image somewhat, moving the bat back so it didn’t obscure his face as much. Gangel also widened Ruth’s stance, and added players and some definition of the stadium to the background.

First Day City: The stamp design was initially unveiled on Ruth’s birthday, February 6, at the Babe Ruth Birthplace Foundation headquarters in Baltimore, Maryland. There had been calls for the stamp to be issued in Baltimore, with promises of parades and festivities if that happened, but the USPS intended to issue the stamp in Chicago in connection with the All-Star Game, which was celebrating its 50th anniversary that year. However, the USPS later realized that a ceremony would be lost in the excitement of the All-Star Game. So, they held a special Day ceremony the day before, July 5, during events connected to the Old Timers’ Game. No stamps were available during this ceremony. Then, on July 6, postal booths were set up throughout the stadium. Within each, a single employee stood affixing stamps and canceling First Day Covers. They sold a total of $12,194 in stamps at the stadium that day. But no First Day ceremony was held on that day.

Unusual fact about this stamp: A paper crease variety is known in which the paper folded over during printing, leaving a white diagonal line across the design.

History the stamp represents: George Herman “Babe” Ruth was born on February 6, 1895, in Baltimore, Maryland.

Ruth was reportedly a rambunctious child with a habit of getting into trouble. It’s likely because of this that he was sent to the St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys, where he stayed for 12 years.

Ruth enjoyed playing baseball at a young age. He was left-handed and played as a catcher, third baseman, and shortstop, all of which were unusual at the time for a lefthander to play. His school’s Prefect of Discipline Brother Matthias Boutlier, noticed his talent for baseball and encouraged him to keep playing. Ruth would later estimate that he played about 200 games a year as he worked his way up to the professional teams.

Ruth began his professional baseball career in 1914, joining the Baltimore Orioles minor league team. Ruth quickly established himself as the team’s star pitcher and was also a very successful batter. Despite Ruth’s top performance, the team gained little attention and the coach opted to sell Ruth and his other star players to the Boston Red Sox to help fund his team.

Ruth would play with the Red Sox from 1914 to 1919. During this time, Ruth grew tired of only playing every few games as a pitcher. He wanted to play every day and eventually convinced the coach to move him to the outfield. The move proved wise, as Ruth earned a .300 batting average and helped lead the team to victory in the 1918 World Series.

The following season, Ruth only pitched in 17 of his 130 games and had an 8-5 record. Though the team wouldn’t make it to the World Series, Ruth had a banner year. He became the first major league player to hit a home run in all eight ballparks in his league. And he broke the major league home run record, finishing the season with 29.

During the break between seasons, something unexpected happened. On December 26, 1919, the Boston Red Sox sold Ruth to the New York Yankees. Even now we don’t know all the details that led to the sale of one of baseball’s most recognizable players. In part, it seems the Red Sox owner needed money.

By the time Ruth became a Yankee, he was already considered one of the greatest hitters in the game. He also possessed a flamboyant playing style and became immensely popular with fans and players alike. This was no more evident than in 1923 when the new Yankee Stadium was nicknamed “the House That Ruth Built.” Crowds packed the stadium game after game, to see what great feats Ruth would accomplish that day.

Possibly the most successful season Ruth experienced was 1927, as part of the legendary “Murderer’s Row.” That year, Ruth batted .356 and brought in 164 runs. Also in 1927, he hit 60 home runs, more homers than any other team in the league and a record that would stand for over thirty years.

But it would be the 1929 season that would bring one of Ruth’s greatest accomplishments. By August of that year, he had racked up an unprecedented 499 home runs. Prior to his game at Cleveland’s League Park on August 11, Babe approached the field’s police chief. He told the chief that he would hit his 500th home run that day and wanted to keep the ball.

True to his word, Ruth hit Willis Hudlin’s first pitch in his first at-bat, high over the right-field wall onto Lexington Avenue. As the game continued, the park police rushed to the street to find the lucky fan. Eventually, they found young Jake Geiser and asked for the ball. When his friend suggested that Jake might want to keep the ball, the police and Cleveland team secretary offered to take him to the Yankee dugout to meet Babe. There, Ruth offered Jake a signed ball for the one he’d hit. Jake obliged and Ruth also gave him $20.

Three years later, Ruth had another memorable home run. It occurred during the 1932 World Series at Chicago’s Wrigley Field. Before hitting the ball, he famously reached his arm out, possibly pointing to where he planned to hit the ball. Whether Ruth actually indicated his intentions to the taunting, lemon-throwing Wrigley Field crowd has been widely debated for years. However, it made for good headlines and added to Ruth’s already legendary reputation.

Over the course of his career, Ruth hit 714 home runs, a record that stood until 1974, when Hank Aaron broke it. Barry Bonds was the only other player to hit more than Aaron. Only 26 men have hit more than 500 home runs, but Ruth has the distinction of being the first.

Not only did Ruth set the standard for home runs in nearly every year he played, but he also set many other records, including 2,056 career walks and 72 games in which he hit two or more home runs. He even hit three home runs in a single World Series game twice.

Ruth played with the Yankees until 1934 and played his final season with the Boston Braves. He briefly served as a first base coach, spoke at Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day and attended the opening of the Baseball Hall of Fame. He also made a number of appearances to support the war effort during World War II.

Ruth’s health declined in his later years and he died on August 16, 1948.