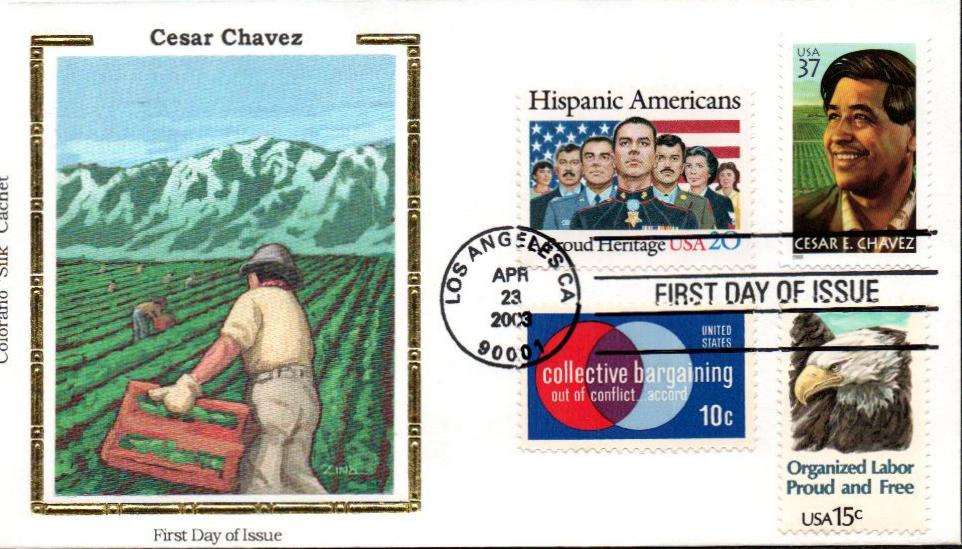

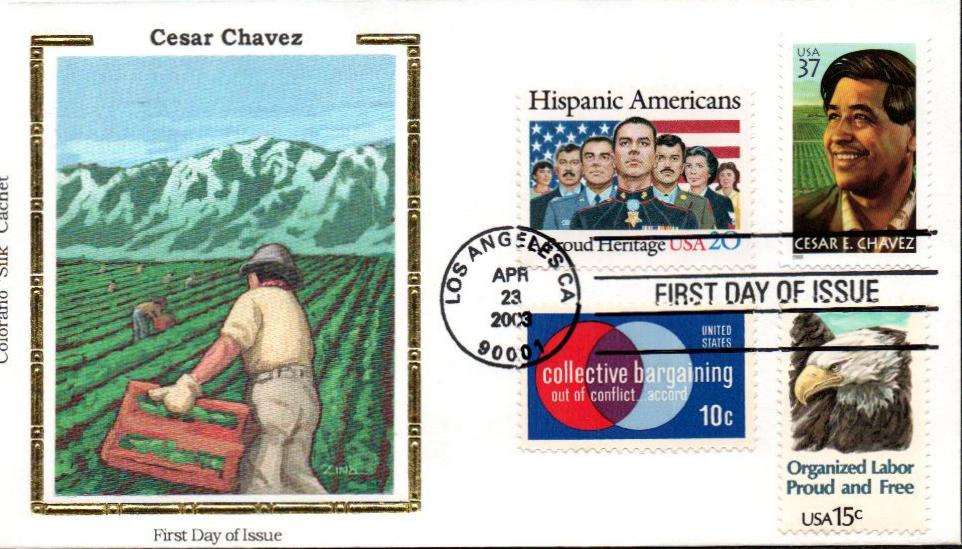

# 1831 FDC - 1980 15c Eagle, Organized Labor

1980 15¢ Organized Labor

City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity: 166,545,000

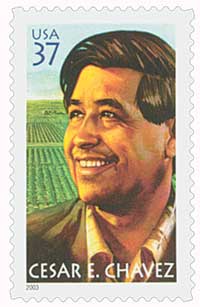

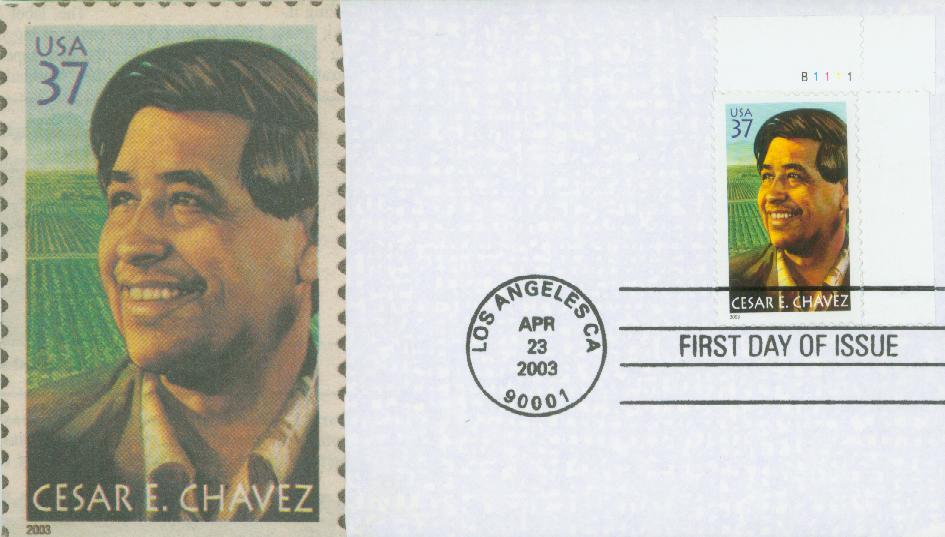

Birth Of César Chávez

When Chávez was 10, his grandmother died and the local government auctioned off the family’s farmstead to pay for back taxes. Chávez and his family then made their way to California. They moved around California quite a bit, finding work as agricultural laborers. On weekends, Chávez joined his family in this work.

Chávez faced frequent prejudice both for his family’s poverty and his race. After graduating from junior high in 1942, he abandoned formal education and worked full-time as a farm laborer. He spent two years in the Navy from 1946 to 1948 before returning to agricultural labor.

After getting married and having three children, Chávez settled in San Jose where he befriended social justice advocates. With their encouragement, he helped established a chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO) and worked on voter registration drives. One of his friends also lent him several books, including some about Mahatma Gandhi that introduced him to the idea of non-violent protest.

Chávez implemented some of these ideas in Oxnard, organizing sit ins to gain attention and better treatment for workers who had been fired or passed over for jobs in favor of cheaper labor.

In 1962, Chávez moved to Delano to form a labor union of farm workers, though he told most people he was simply conducting a census of farm workers to figure out their needs. Chávez began formulating a plan for the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). He spent his days meeting with workers and encouraging them to join. He officially formed the NFWA at a convention on September 30, 1962 and was elected its president the following year. They adopted the motto “viva la causa” or “long live the cause.” Chávez also established an insurance policy and credit union for members.

The NFWA expanded rapidly, drawing volunteers from around the country. In May 1965, they organized their first strike for a group of rose grafters. After a four-day strike, the two companies they targeted agreed to raise wages and they returned to work.

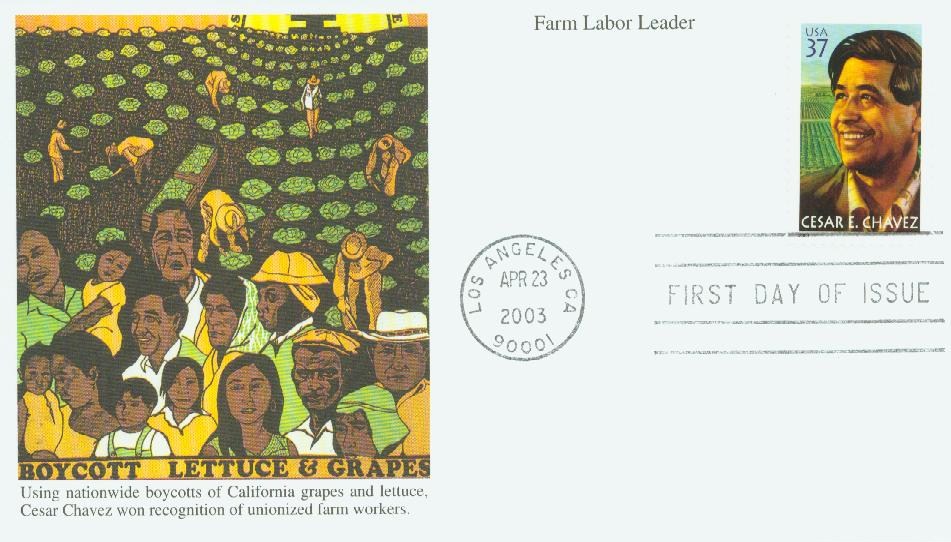

Also in 1965, Chávez and the NFWA joined in the Delano grape strike. The strike began on September 8, 1965, when a group of migrant farm workers refused to harvest grapes. The workers demanded an increase in wages in accordance with the federal minimum wage. One week later, Chavez and the NFWA joined the strike. More than 2,000 workers eventually joined in the strike.

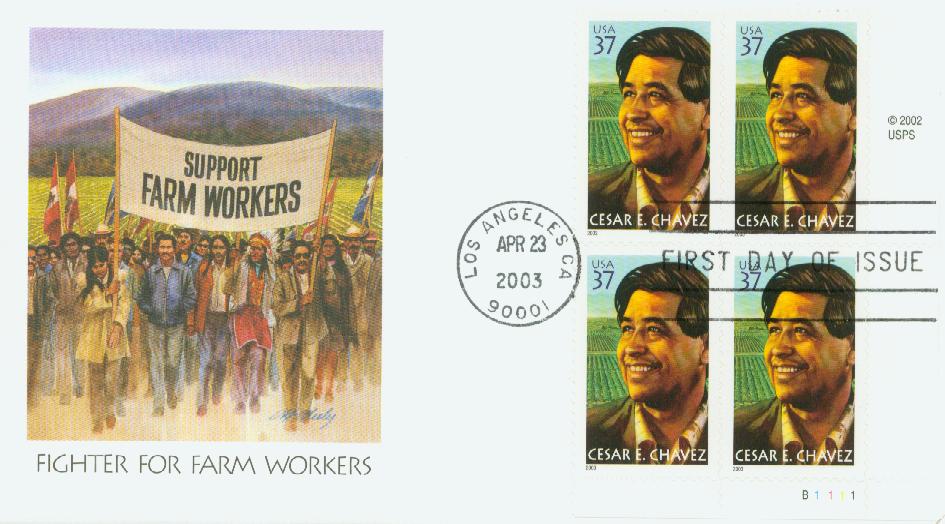

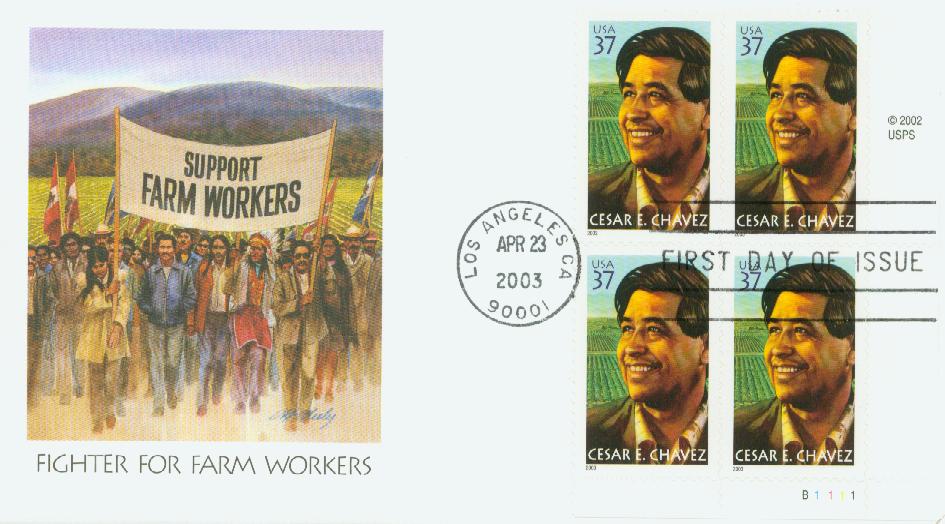

In March of 1966, Chavez led 75 protesters on a 340-mile march from Delano, California, to Sacramento to focus attention on the plight of agricultural workers. The movement gained national media attention through its use of boycotts and nonviolent resistance.

Then in August 1966, the NFWA joined forces with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee to create the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, which later became the United Farm Workers (UFW). They adopted pacifist tactics including hunger strikes, boycotts, marches, rallies, and public relations campaigns. They soon began organizing agricultural labor unions and even negotiated contracts.

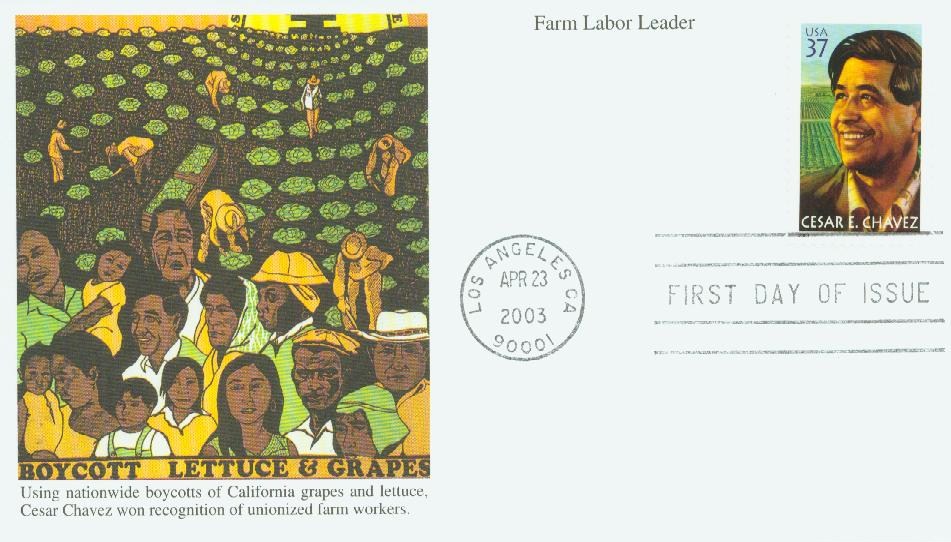

It wasn’t until June 1969 that about 25 growers gave up their fight and the strike ended. While many expected this to lead other growers to recognize the UFW, it instead led to another dispute between workers and the lettuce industry. Eventually, up to 7,000 UFW workers went on strike – the largest strike in US history up to that point. Despite continued attempts, a long-lasting agreement wasn’t reached until 1977.

In 1975, Chávez organized a 110-mile march from San Francisco to Modesto that drew out 15,000 participants and gained national media attention. This showed the UFW still had strong support and led the governor of California to sign the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which established collective bargaining for farm workers.

In the late 1970s and 80s, membership in the UFW declined and Chávez clashed frequently with the group’s leaders and members, as he attempted to steer the organization in a new direction. Chávez attempted to lead another grape boycott and fasted for 35 days, which caused several health problems and may have contributed to his death on April 23, 1993. In 2014, Chávez’s birthday was declared a federal commemorative holiday.

1980 15¢ Organized Labor

City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity: 166,545,000

Birth Of César Chávez

When Chávez was 10, his grandmother died and the local government auctioned off the family’s farmstead to pay for back taxes. Chávez and his family then made their way to California. They moved around California quite a bit, finding work as agricultural laborers. On weekends, Chávez joined his family in this work.

Chávez faced frequent prejudice both for his family’s poverty and his race. After graduating from junior high in 1942, he abandoned formal education and worked full-time as a farm laborer. He spent two years in the Navy from 1946 to 1948 before returning to agricultural labor.

After getting married and having three children, Chávez settled in San Jose where he befriended social justice advocates. With their encouragement, he helped established a chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO) and worked on voter registration drives. One of his friends also lent him several books, including some about Mahatma Gandhi that introduced him to the idea of non-violent protest.

Chávez implemented some of these ideas in Oxnard, organizing sit ins to gain attention and better treatment for workers who had been fired or passed over for jobs in favor of cheaper labor.

In 1962, Chávez moved to Delano to form a labor union of farm workers, though he told most people he was simply conducting a census of farm workers to figure out their needs. Chávez began formulating a plan for the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). He spent his days meeting with workers and encouraging them to join. He officially formed the NFWA at a convention on September 30, 1962 and was elected its president the following year. They adopted the motto “viva la causa” or “long live the cause.” Chávez also established an insurance policy and credit union for members.

The NFWA expanded rapidly, drawing volunteers from around the country. In May 1965, they organized their first strike for a group of rose grafters. After a four-day strike, the two companies they targeted agreed to raise wages and they returned to work.

Also in 1965, Chávez and the NFWA joined in the Delano grape strike. The strike began on September 8, 1965, when a group of migrant farm workers refused to harvest grapes. The workers demanded an increase in wages in accordance with the federal minimum wage. One week later, Chavez and the NFWA joined the strike. More than 2,000 workers eventually joined in the strike.

In March of 1966, Chavez led 75 protesters on a 340-mile march from Delano, California, to Sacramento to focus attention on the plight of agricultural workers. The movement gained national media attention through its use of boycotts and nonviolent resistance.

Then in August 1966, the NFWA joined forces with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee to create the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, which later became the United Farm Workers (UFW). They adopted pacifist tactics including hunger strikes, boycotts, marches, rallies, and public relations campaigns. They soon began organizing agricultural labor unions and even negotiated contracts.

It wasn’t until June 1969 that about 25 growers gave up their fight and the strike ended. While many expected this to lead other growers to recognize the UFW, it instead led to another dispute between workers and the lettuce industry. Eventually, up to 7,000 UFW workers went on strike – the largest strike in US history up to that point. Despite continued attempts, a long-lasting agreement wasn’t reached until 1977.

In 1975, Chávez organized a 110-mile march from San Francisco to Modesto that drew out 15,000 participants and gained national media attention. This showed the UFW still had strong support and led the governor of California to sign the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which established collective bargaining for farm workers.

In the late 1970s and 80s, membership in the UFW declined and Chávez clashed frequently with the group’s leaders and members, as he attempted to steer the organization in a new direction. Chávez attempted to lead another grape boycott and fasted for 35 days, which caused several health problems and may have contributed to his death on April 23, 1993. In 2014, Chávez’s birthday was declared a federal commemorative holiday.