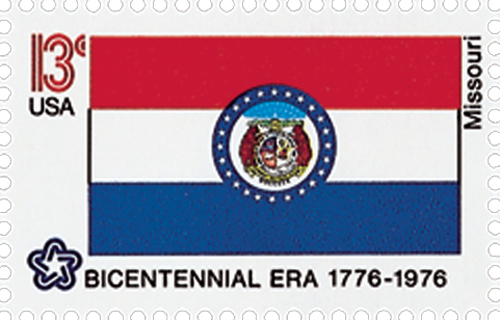

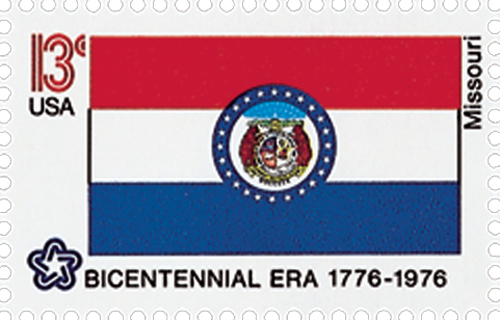

# 1656 FDC - 1976 13c State Flags: Missouri

State Flags Issue

Missouri Becomes 24th State

On August 10, 1821, President James Monroe signed legislation adding Missouri to the Union as our 24th state.

Long before Europeans came to Missouri, a group of Indians known as the Mound Builders constructed large earthworks throughout the region. Many of these mounds can still be found there. However, this culture had disappeared by the time of European exploration.

The first European explorers in Missouri found Missouri Indians living in the east-central portion of the state, the Osage in the south and west, and the Fox, Sauk and other tribes living in the north.

The French explorers Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet were probably the first white people to see the mouth of the Missouri River. In 1673, they discovered the point where the Missouri joins the mighty Mississippi River. René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, sailed down the Mississippi in 1682 and claimed the entire river valley for France. He named it Louisiana, in honor of King Louis XIV.

Soon after, Frenchmen involved with the fur-trading business began to settle in the region, founding trading posts along the river. Around 1700, Jesuit missionaries founded the first European settlement in Missouri, the Mission of St. Francis Xavier, near today’s St. Louis. This mission was abandoned three years later due to its proximity to an unhealthful swamp. Settlers from what is now Illinois founded the first permanent white settlement at Ste. Genevieve. In 1764, Pierre Laclède Liguest and René Auguste Chouteau founded St. Louis.

In 1762, France sold to Spain all of its land west of the Mississippi. Spain encouraged many settlers in the East to take land in Missouri. Among these pioneers was the legendary Daniel Boone. In 1800, Napoleon Bonaparte of France forced Spain to give these lands back to France. Then, to raise badly needed funds, Napoleon sold the Louisiana Territory to the United States in 1803.

When the U.S. took ownership of Missouri, most of the land had already been explored. Many communities had already been founded, and farming and mineral industries had been developed. Missouri was made a part of Upper Louisiana; then, in 1812, the Missouri Territory was organized.

As settlers began to pour into Missouri, they also took the traditional hunting grounds of the Indians in the area. The Indians started staging raids against the settlers. When the War of 1812 broke out, the British armed the Indians in Missouri and encouraged them to attack white settlements. These attacks continued even after the conclusion of the war. Peace finally came to the region in 1815, with the treaty at Portage des Sioux.

Missouri first asked to be granted statehood in 1818. At that time, the country was becoming divided by the practice of slavery and its expansion into new territories. These disputes delayed Missouri’s statehood until Congress passed the Missouri Compromise. Under this law, Missouri entered the Union as a slave state on August 10, 1821. The state’s population was 66,586 people – 10,222 of which were slaves. In 1836, the U.S. bought the area of Platte County from the Indians and expanded the state’s territory, making the Missouri River its western border.

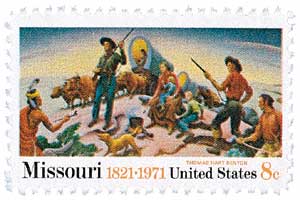

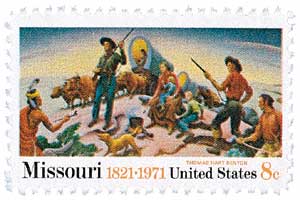

Missouri represented America’s western frontier. Before the American Civil War, the state’s fur industry was its main source of revenue. Trade from the Santa Fe and Oregon Trails also enriched it.

Even before the Civil War began, Missouri had become involved in armed conflict over slavery, when clashes with anti-slavery families from Kansas erupted. This fighting between individuals and families continued well into the Civil War.

In 1861, the nation focused its attention on Missouri to see if it would leave the Union. The governor, Claiborne F. Jackson, held a state convention to determine the will of the people. Despite its pro-slavery leadership, the convention voted to remain in the Union, but remain neutral in any fighting.

In April of 1861, President Abraham Lincoln asked Missouri for troops, and Missouri refused. This led to the first real fighting of the Civil War in the state. The Union soon came to control the northern portion of the state, while the Confederates held on to the south. In 1864, Union forces won a decisive victory near today’s Kansas City, which ended all full-scale fighting in the state. However, guerrilla forces on both sides continued to terrorize the countryside.

After the war, Missouri began to change at a rapid pace. St. Louis and Kansas City became important travel centers. The fur trade lost its profitability. Industry began to grow. In 1904, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition was held in St. Louis. It attracted nearly 20 million visitors from all over the U.S. and around the world. One of the popular exhibitions at the exposition featured automobiles.

With the start of World War I, Missouri’s mining and manufacturing businesses flourished. Bagnell Dam, an important hydroelectric power source, was completed in 1931. This growth continued through World War II. In the 1950s, high-technology companies began to spread throughout the state. The discovery of large iron deposits during the 1960s also brought Missouri increased revenue.

The state’s farms were among those hit by the farming crisis of the 1980s. Urban decay and environmental problems also surfaced at that time. However, the state’s economy remains strong. It remains a leader in the production of livestock, soybeans, corn, wheat, and cotton. The state’s aerospace industry has done especially well, and it continues to expand.

Tourism has provided a huge economic boost for Missouri. Each year, tourists spend a billion dollars in the state. St. Louis, Kansas City, and Springfield have outstanding facilities to serve as convention centers for business, religious, and political organizations.

State Flags Issue

Missouri Becomes 24th State

On August 10, 1821, President James Monroe signed legislation adding Missouri to the Union as our 24th state.

Long before Europeans came to Missouri, a group of Indians known as the Mound Builders constructed large earthworks throughout the region. Many of these mounds can still be found there. However, this culture had disappeared by the time of European exploration.

The first European explorers in Missouri found Missouri Indians living in the east-central portion of the state, the Osage in the south and west, and the Fox, Sauk and other tribes living in the north.

The French explorers Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet were probably the first white people to see the mouth of the Missouri River. In 1673, they discovered the point where the Missouri joins the mighty Mississippi River. René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, sailed down the Mississippi in 1682 and claimed the entire river valley for France. He named it Louisiana, in honor of King Louis XIV.

Soon after, Frenchmen involved with the fur-trading business began to settle in the region, founding trading posts along the river. Around 1700, Jesuit missionaries founded the first European settlement in Missouri, the Mission of St. Francis Xavier, near today’s St. Louis. This mission was abandoned three years later due to its proximity to an unhealthful swamp. Settlers from what is now Illinois founded the first permanent white settlement at Ste. Genevieve. In 1764, Pierre Laclède Liguest and René Auguste Chouteau founded St. Louis.

In 1762, France sold to Spain all of its land west of the Mississippi. Spain encouraged many settlers in the East to take land in Missouri. Among these pioneers was the legendary Daniel Boone. In 1800, Napoleon Bonaparte of France forced Spain to give these lands back to France. Then, to raise badly needed funds, Napoleon sold the Louisiana Territory to the United States in 1803.

When the U.S. took ownership of Missouri, most of the land had already been explored. Many communities had already been founded, and farming and mineral industries had been developed. Missouri was made a part of Upper Louisiana; then, in 1812, the Missouri Territory was organized.

As settlers began to pour into Missouri, they also took the traditional hunting grounds of the Indians in the area. The Indians started staging raids against the settlers. When the War of 1812 broke out, the British armed the Indians in Missouri and encouraged them to attack white settlements. These attacks continued even after the conclusion of the war. Peace finally came to the region in 1815, with the treaty at Portage des Sioux.

Missouri first asked to be granted statehood in 1818. At that time, the country was becoming divided by the practice of slavery and its expansion into new territories. These disputes delayed Missouri’s statehood until Congress passed the Missouri Compromise. Under this law, Missouri entered the Union as a slave state on August 10, 1821. The state’s population was 66,586 people – 10,222 of which were slaves. In 1836, the U.S. bought the area of Platte County from the Indians and expanded the state’s territory, making the Missouri River its western border.

Missouri represented America’s western frontier. Before the American Civil War, the state’s fur industry was its main source of revenue. Trade from the Santa Fe and Oregon Trails also enriched it.

Even before the Civil War began, Missouri had become involved in armed conflict over slavery, when clashes with anti-slavery families from Kansas erupted. This fighting between individuals and families continued well into the Civil War.

In 1861, the nation focused its attention on Missouri to see if it would leave the Union. The governor, Claiborne F. Jackson, held a state convention to determine the will of the people. Despite its pro-slavery leadership, the convention voted to remain in the Union, but remain neutral in any fighting.

In April of 1861, President Abraham Lincoln asked Missouri for troops, and Missouri refused. This led to the first real fighting of the Civil War in the state. The Union soon came to control the northern portion of the state, while the Confederates held on to the south. In 1864, Union forces won a decisive victory near today’s Kansas City, which ended all full-scale fighting in the state. However, guerrilla forces on both sides continued to terrorize the countryside.

After the war, Missouri began to change at a rapid pace. St. Louis and Kansas City became important travel centers. The fur trade lost its profitability. Industry began to grow. In 1904, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition was held in St. Louis. It attracted nearly 20 million visitors from all over the U.S. and around the world. One of the popular exhibitions at the exposition featured automobiles.

With the start of World War I, Missouri’s mining and manufacturing businesses flourished. Bagnell Dam, an important hydroelectric power source, was completed in 1931. This growth continued through World War II. In the 1950s, high-technology companies began to spread throughout the state. The discovery of large iron deposits during the 1960s also brought Missouri increased revenue.

The state’s farms were among those hit by the farming crisis of the 1980s. Urban decay and environmental problems also surfaced at that time. However, the state’s economy remains strong. It remains a leader in the production of livestock, soybeans, corn, wheat, and cotton. The state’s aerospace industry has done especially well, and it continues to expand.

Tourism has provided a huge economic boost for Missouri. Each year, tourists spend a billion dollars in the state. St. Louis, Kansas City, and Springfield have outstanding facilities to serve as convention centers for business, religious, and political organizations.