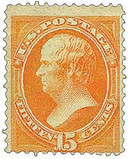

U.S. #152

1870-71 15¢ Webster

National Bank Note Printing

Earliest Known Use: June 24, 1870

Quantity issued: 5,033,300 (estimate)

Printed by: National Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Bright orange

A Senator for twenty years and twice Secretary of State, Daniel Webster was an eloquent spokesman for the Union in the years before the Civil War.

Bank Notes 1870-1888

Due to the unpopularity of the 1869 Pictorial series, the Postmaster General found it necessary to issue new stamps. Among the public’s many complaints were that the stamps were too small, unattractive, and of inferior quality. Thus, the new issues were not only larger and better quality, but they also carried new designs. Heads, in profile, of famous deceased Americans were chosen as the new subject matter.

Nicknamed the “Bank Note” stamps, this series was printed by three prominent Bank Note printing companies – the National, Continental, and American Bank Note Companies, in that order. As the contract for printing passed from company to company, so did the dies and plates. Each company printed the stamps with slight variations, and identifying them can be both challenging and complex.

Because the pictorials were to be printed for four years, but were withdrawn from sale after a year, the National Bank Note Company still had three years remaining in their contract. The stamps they printed were produced with and without grills.

In 1873, new bids were submitted and a new contract was awarded to the Continental Bank Note Company. So-called “secret marks” enabled them to distinguish their plates and stamps from earlier ones.

The American Bank Note Company acquired Continental in 1879 and assumed the contract Continental had held. This firm, however, printed the stamps on a soft paper, which has different qualities than the hard paper used by the previous companies.

Color variations, in addition to secret marks and different paper types, are helpful in determining the different varieties. These classic stamps are a truly fascinating area of philately.

Webster’s Stamp Proposal

On June 10, 1840, Senator Daniel Webster submitted a resolution to the US Congress recommending that the US issue stamps.

Webster’s proposal had been inspired by the issue of the world’s first postage stamp, the Penny Black, in Great Britain a month earlier on May 1. All eyes were on Great Britain to see how their experiment would turn out.

In America, the US Post Office was struggling with increasing annual deficits. This was in large part due to the complicated and pricey system of postal rates. Additionally, many letters were sent with the expectation that the addressee would pay for the postage, but they often refused. This meant the Post Office carried these letters, sometimes long distances, and never received any payment for them.

Webster was convinced that the US should follow Great Britain’s example and immediately began formulating a resolution to propose a similar system in America. To help support his case, Webster commissioned William J. Stone to reproduce engravings of the Penny Black and the Mulready envelope to accompany his resolution. In later years, many would remark that Stone’s engraving was superior to the Mulready envelopes produced in Great Britain.

On June 10, 1840, Webster addressed the 26th Session of Congress with his resolution, sharing his reproductions and arguing in favor of new rates and stamps. Among his points were “That the rates of postage charged on letters transmitted by the mails of the United States ought to be reduced.” And he went on to say “That it is expedient to inquire into the utility of so altering the present regulations of the Post Office Department as to connect the use of stamps, or stamped covers, with a large reduction in the rates of postage.”

Despite his convincing and impassioned presentation, Congress took no action. At the time, many feared that reducing postage rates would only increase the Post Office’s deficit. It would take five years for them to pass the Postal Act of 1845, which set uniform nationwide postal rates. And it would be another two years before they issued America’s first postage stamps in July 1847.