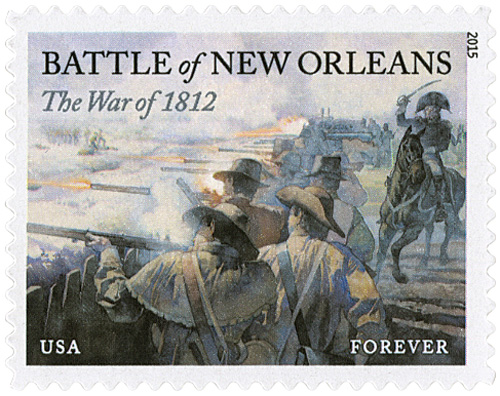

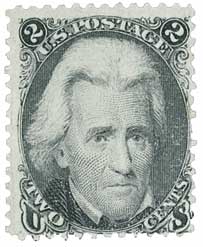

# 1261 FDC - 1965 5c Battle of New Orleans

5¢ Battle of New Orleans

City: New Orleans, LA

Quantity: 115,695,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Deep carmine, violet blue, and gray

The Battle Of New Orleans Begins

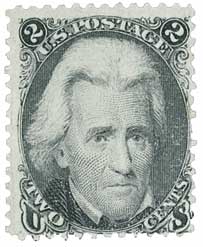

On January 8, 1815, future president Andrew Jackson began the Battle of New Orleans, two weeks after the Treaty of Ghent was signed.

After more than two years of fighting, American and British diplomats met in Belgium in December 1814 to talk peace and end the War of 1812. At the same time, British troops in America prepared a three-pronged invasion they hoped would also bring an end to the war. After their first two attempts at Baltimore and Plattsburg failed, the British set their sights on New Orleans, a strategically important seaport that served as a gateway to the west.

Meanwhile, Andrew Jackson, or “Old Hickory” as his men called him, learned of the British plans for New Orleans and rushed to prepare the city’s defenses. Jackson had been taken prisoner by the British during the Revolutionary War and was anxious to face them, claiming, “I owe to Britain a debt of retaliatory vengeance… should our forces meet I trust I shall pay the debt.”

In the coming days, Jackson declared martial law in New Orleans and gathered every weapon and able-bodied man to help defend the city. Soon, Jackson amassed a force of 4,500 militiamen, army regulars, aristocrats, Choctaw, and even pirates. However, as they’d soon find out, they were facing off against some 8,000 British invaders.

The two forces first clashed on December 23, when Jackson led a nighttime attack on the British position south of New Orleans. Jackson then led his men back to the Rodriguez Canal and had them widen it into a trench, proclaiming, “Here we shall plant our stake… and not abandon them until we drive these red-coat rascals into the river, or the swamp.” After a skirmish on December 28 and large artillery duel on January 1, the British revised their plan. One force would cross the Mississippi and take an American battery while a larger group would charge the Rodriguez Canal.

The British attack began around sunrise on January 8. As both sides exchanged artillery fire, the smaller British group managed to capture an American redoubt. But as the British commander yelled, “Hurrah, boys, the day is ours!” he was shot and killed, sending his men into a frantic retreat.

Not far away, the British main line had even less success. American cannons shot huge gaps in the attacking British line. General Jackson yelled, “Give it to them, my boys! Let us finish the business today!” In less than 30 minutes, most of the British officers were killed or wounded. Some of them made a second attempt to capture the American battery, but were unable to hold it for long.

It was a resounding victory for the Americans, who lost less than 60 men, while the British suffered over 2,000 casualties. New Orleans was the last major battle of the war – and also the most one-sided. Some British troops remained in the area for several days, and even launched a failed naval attack, before sailing to the Gulf of Mexico.

Jackson was an instant hero. He marched into New Orleans to the tune of “Yankee Doodle” as the city’s inhabitants cheered him on. Because news traveled slow in those days, what Jackson didn’t realize was that the Treaty of Ghent had been signed by both nations weeks before, on December 24, effectively ending the war. The victory at New Orleans was not decisive in the outcome of the war. But it renewed American patriotism and ensured the U.S. ratification of the treaty (which came in February). It also made the 47-year-old Andrew Jackson a national hero, paving the path to his presidency over a decade later.

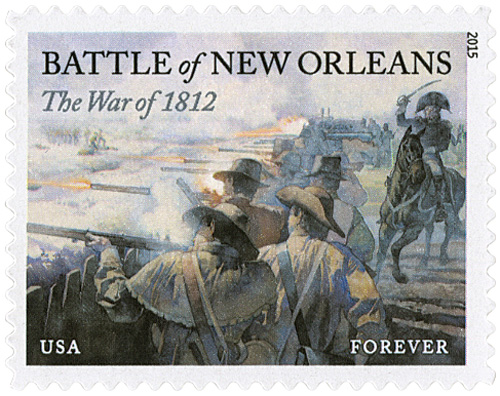

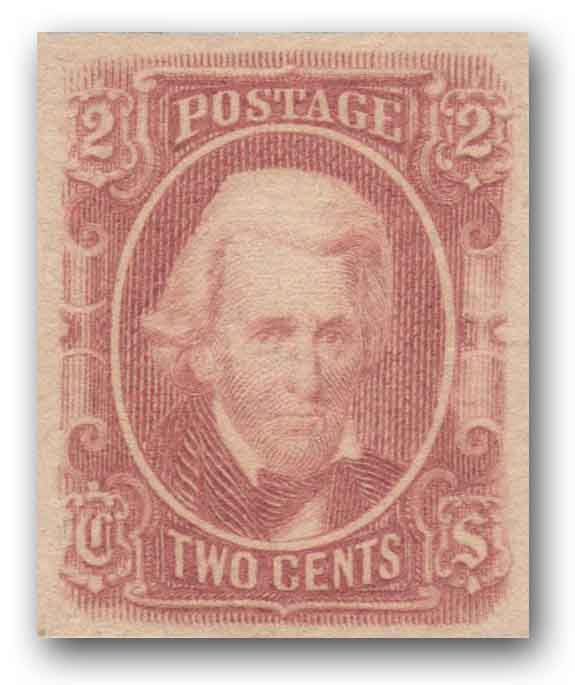

5¢ Battle of New Orleans

City: New Orleans, LA

Quantity: 115,695,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Deep carmine, violet blue, and gray

The Battle Of New Orleans Begins

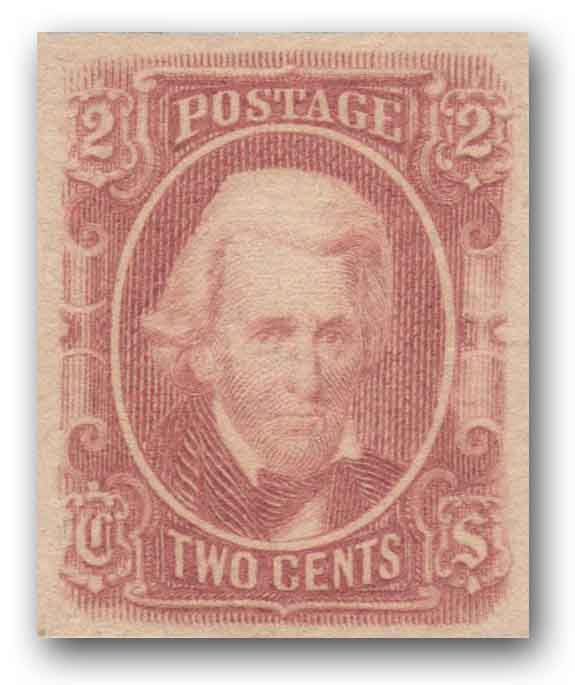

On January 8, 1815, future president Andrew Jackson began the Battle of New Orleans, two weeks after the Treaty of Ghent was signed.

After more than two years of fighting, American and British diplomats met in Belgium in December 1814 to talk peace and end the War of 1812. At the same time, British troops in America prepared a three-pronged invasion they hoped would also bring an end to the war. After their first two attempts at Baltimore and Plattsburg failed, the British set their sights on New Orleans, a strategically important seaport that served as a gateway to the west.

Meanwhile, Andrew Jackson, or “Old Hickory” as his men called him, learned of the British plans for New Orleans and rushed to prepare the city’s defenses. Jackson had been taken prisoner by the British during the Revolutionary War and was anxious to face them, claiming, “I owe to Britain a debt of retaliatory vengeance… should our forces meet I trust I shall pay the debt.”

In the coming days, Jackson declared martial law in New Orleans and gathered every weapon and able-bodied man to help defend the city. Soon, Jackson amassed a force of 4,500 militiamen, army regulars, aristocrats, Choctaw, and even pirates. However, as they’d soon find out, they were facing off against some 8,000 British invaders.

The two forces first clashed on December 23, when Jackson led a nighttime attack on the British position south of New Orleans. Jackson then led his men back to the Rodriguez Canal and had them widen it into a trench, proclaiming, “Here we shall plant our stake… and not abandon them until we drive these red-coat rascals into the river, or the swamp.” After a skirmish on December 28 and large artillery duel on January 1, the British revised their plan. One force would cross the Mississippi and take an American battery while a larger group would charge the Rodriguez Canal.

The British attack began around sunrise on January 8. As both sides exchanged artillery fire, the smaller British group managed to capture an American redoubt. But as the British commander yelled, “Hurrah, boys, the day is ours!” he was shot and killed, sending his men into a frantic retreat.

Not far away, the British main line had even less success. American cannons shot huge gaps in the attacking British line. General Jackson yelled, “Give it to them, my boys! Let us finish the business today!” In less than 30 minutes, most of the British officers were killed or wounded. Some of them made a second attempt to capture the American battery, but were unable to hold it for long.

It was a resounding victory for the Americans, who lost less than 60 men, while the British suffered over 2,000 casualties. New Orleans was the last major battle of the war – and also the most one-sided. Some British troops remained in the area for several days, and even launched a failed naval attack, before sailing to the Gulf of Mexico.

Jackson was an instant hero. He marched into New Orleans to the tune of “Yankee Doodle” as the city’s inhabitants cheered him on. Because news traveled slow in those days, what Jackson didn’t realize was that the Treaty of Ghent had been signed by both nations weeks before, on December 24, effectively ending the war. The victory at New Orleans was not decisive in the outcome of the war. But it renewed American patriotism and ensured the U.S. ratification of the treaty (which came in February). It also made the 47-year-old Andrew Jackson a national hero, paving the path to his presidency over a decade later.