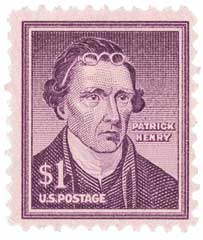

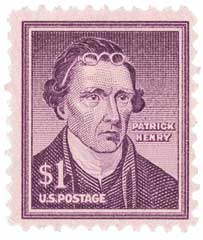

# 1052 - 1955 Liberty Series - $1 Patrick Henry

$1 Patrick Henry

Liberty Series

City: Joplin, MO

Printing Method: Rotary Press dry printing

Perforations: 11 x 10.5

Color: Purple

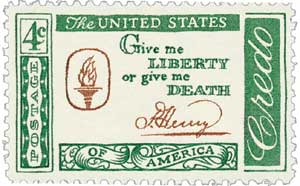

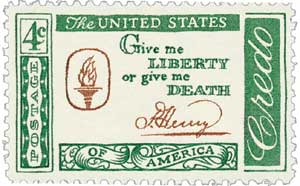

Patrick Henry Delivers Famous Speech

On March 23, 1775, Patrick Henry addressed the Second Virginia Convention to convince them to raise a militia.

Virginia native Patrick Henry was a prominent statesman best remembered for his fiery speeches that helped inspire the American Revolution. Henry was born in Hanover County, Virginia, and attended public schools for a short time. Although he was quite capable intellectually, it was generally understood that Henry lacked ambition at an early age. His father assumed responsibility for Henry’s education, and eventually set the young man up with a business that he soon bankrupted.

Henry received his license to practice law after just six weeks of study and quickly made a name for himself in a lawsuit known as the “Parson’s Cause.” The case concerned the question of whether the price of tobacco paid to clergy for their services should be set by the Colonial government or the Crown. In a brilliant oration, Henry cited a basic constitutional principle in English law, which held that only a representative assembly had the power to levy taxes on the people it represents. Because the colonists had no representation in the assembly, Henry argued, the King had no right to tax them. The first seeds of revolution were sown with Henry’s courtroom victory over the English crown.

In 1765, Henry was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses (the legislative body of the Virginia colony.) He soon became a leader and advocated the causes of less fortunate individuals against the old aristocracy. Henry also upheld the rights given to the colonies in their charters.

Henry proposed the Virginia Stamp Act Resolutions in 1765, which continued his argument against taxation without representation. He extended the argument to assert that the Colonial assemblies had the exclusive right to tax the colonies and could not assign those rights to the Crown. As accusations of treason rose from the assembly, Henry is said to have proclaimed, “If this be treason, make the most of it.”

Henry is best known for his March 23, 1775, speech to the Second Virginia Convention in Richmond. Days earlier Henry presented a number of resolutions supporting his idea that they needed to raise a militia. However, several present opposed his idea, believing they should be cautious and wait until the British crown replied to Congress’ most recent petition for peace.

The deeply divided house was close to deciding against committing troops when Henry rose to speak. He ended the profound speech with his most famous words, “I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!” The speech is credited with convincing Virginians to join the Revolutionary War.

Patrick Henry led a military force from Virginia during the Revolutionary War. Then, in 1776, he was elected to the first of five terms as Virginia’s governor. Two years later, Henry voted in opposition of the U.S. Constitution. However, he accepted its ultimate ratification and was instrumental in framing its first 10 amendments, which are known as the Bill of Rights. Henry died at his estate in Brookneal, Virginia, in 1799.

Click here to read the full text of Henry’s speech.

Governor of Virginia

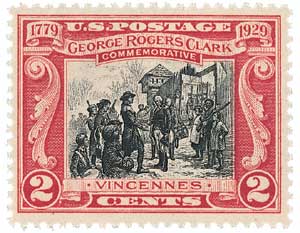

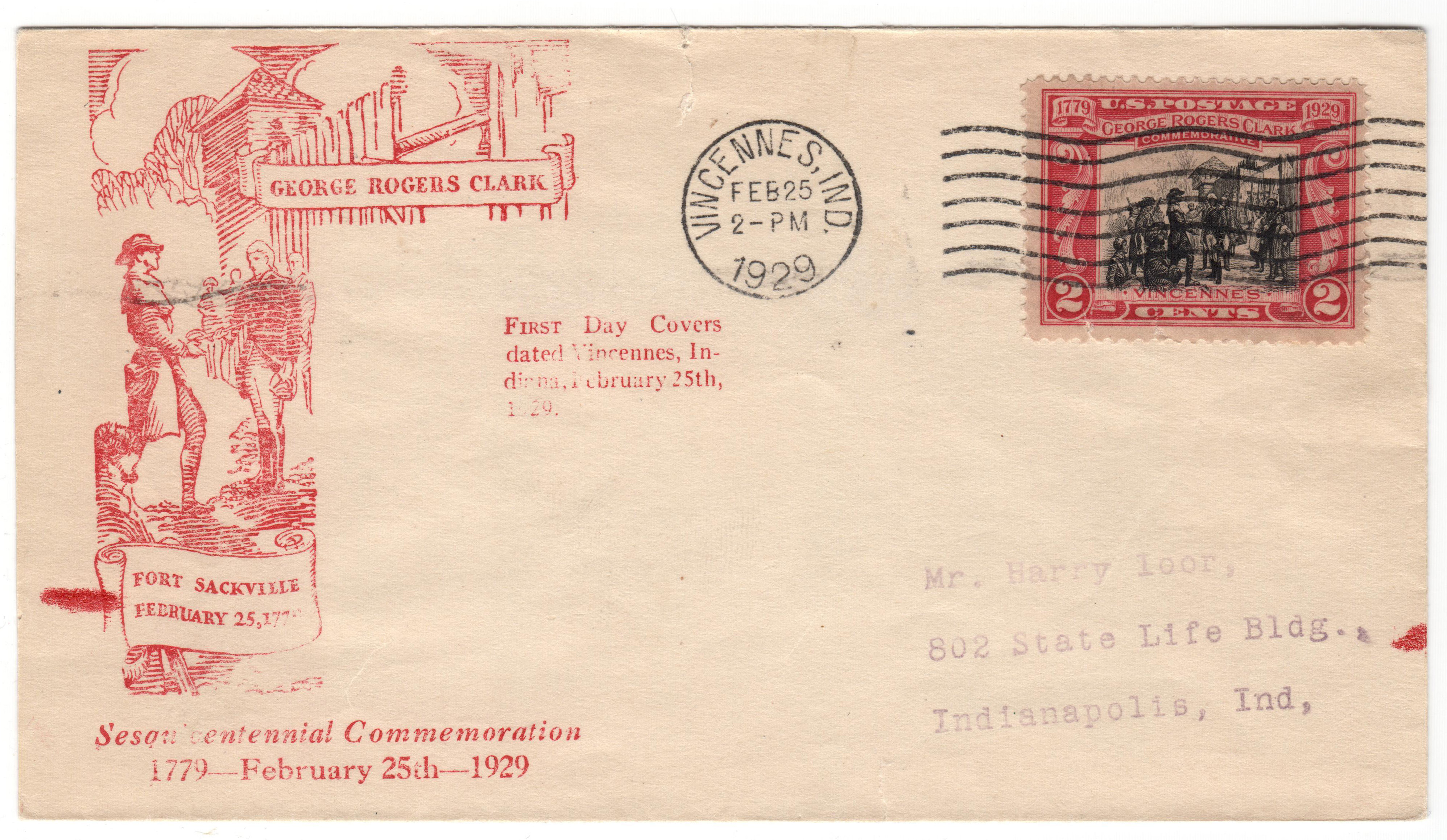

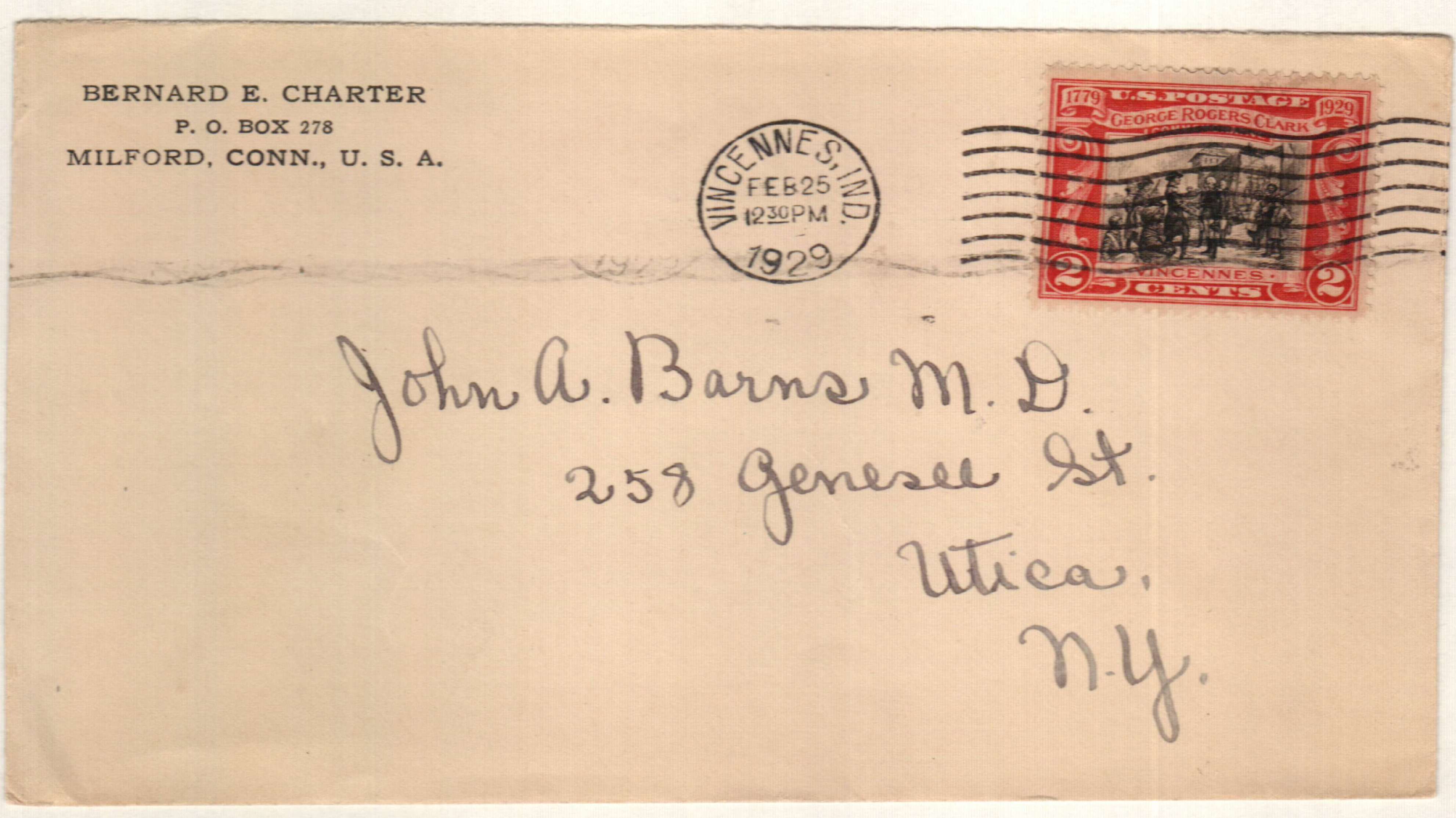

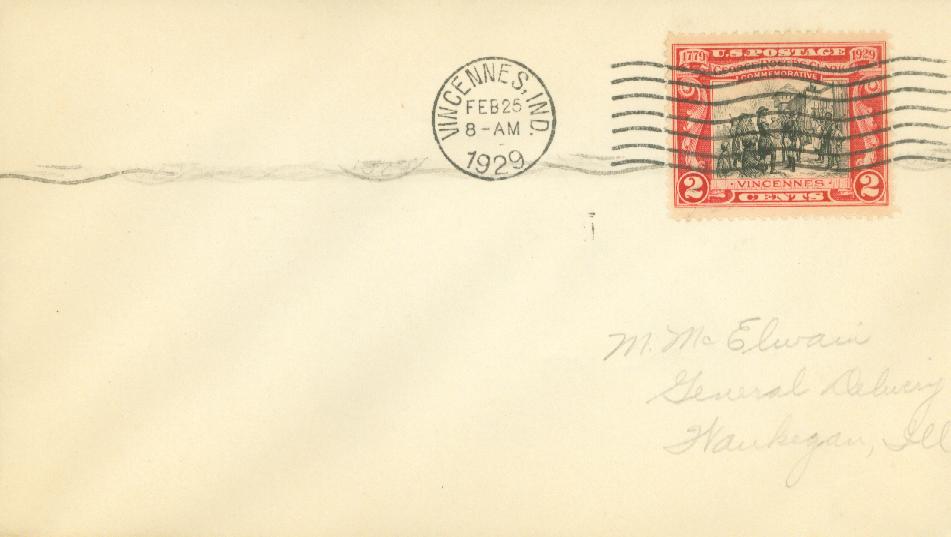

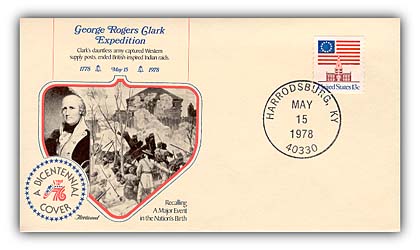

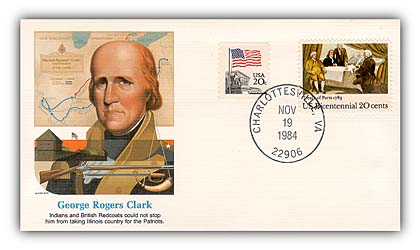

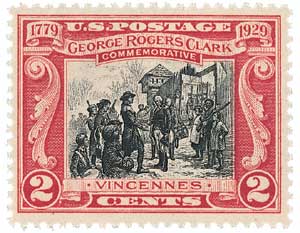

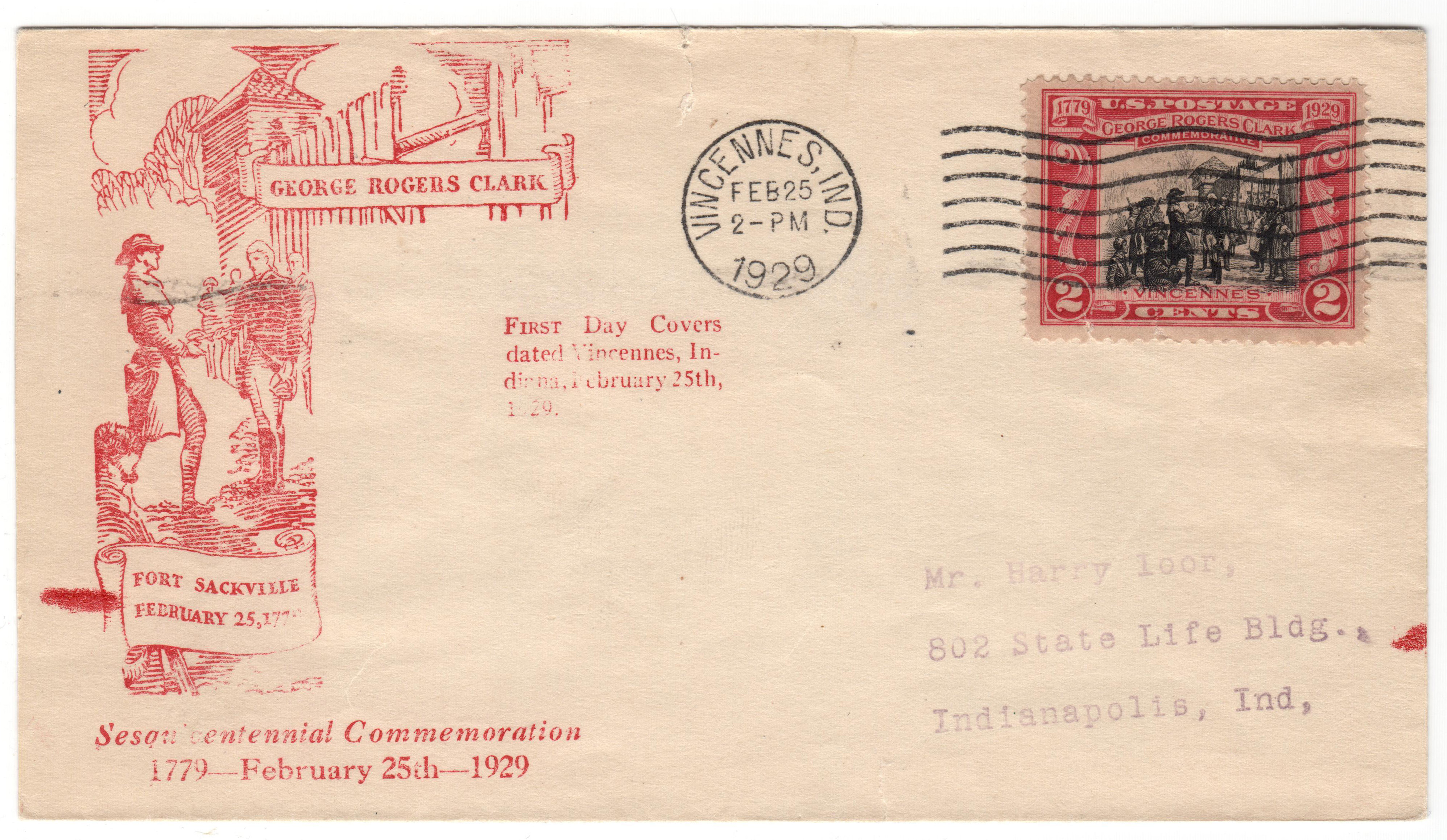

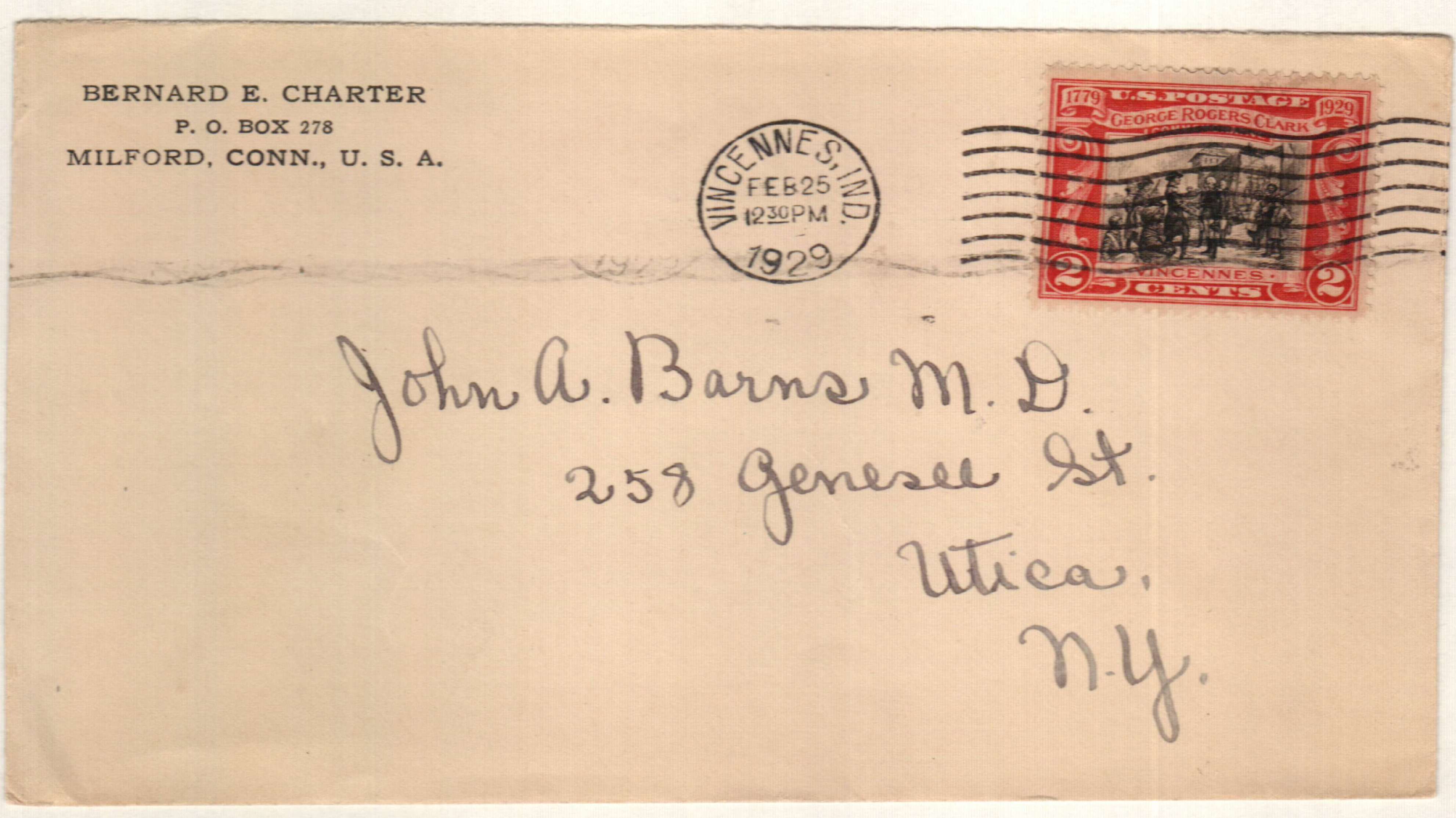

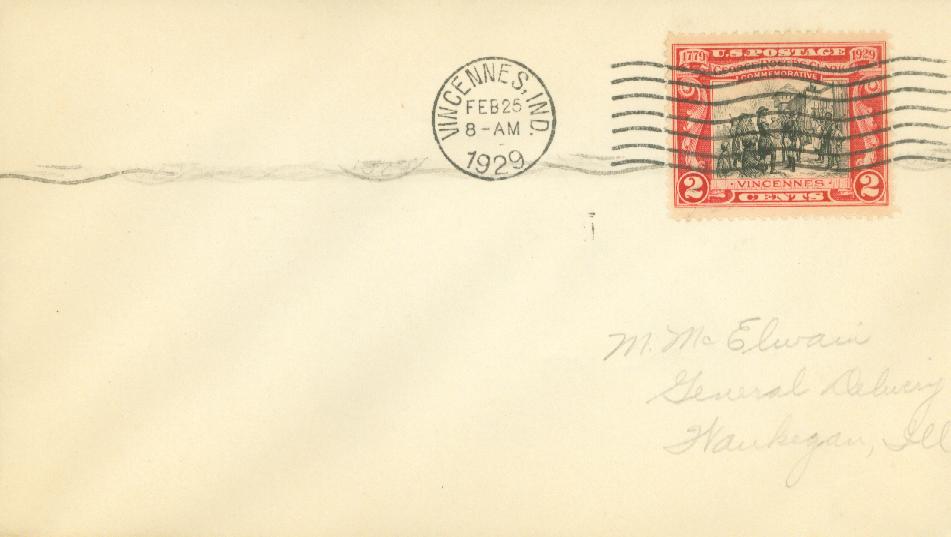

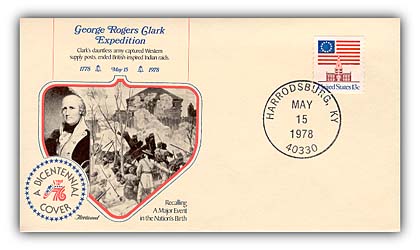

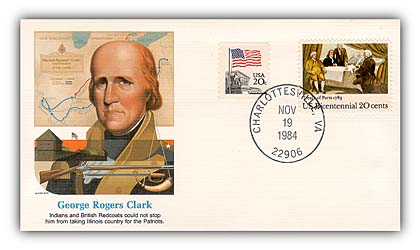

Siege Of Vincennes

On February 24, 1779, George Rogers Clark led a siege of Vincennes, forcing the British to surrender.

After the French and Indian War, the British occupied the majority of the trans-Appalachian frontier. They soon passed the Proclamation of 1763, making the settlement of land west of the Appalachian Mountains illegal for colonists. The British responded harshly to settlers who ignored this decree, sending Native American war parties after trespassers.

In Kentucky, George Rogers Clark led a militia to defend the people against these attacks. However, Clark soon decided he would rather cut the attacks off at their British source. Clark developed a plan of action and brought it to Virginia governor Patrick Henry, who quickly approved it. By the summer of 1778, Clark and his army of militiamen were on their way down the Ohio River.

The men traveled over 120 miles before they reached and captured the British outposts at Kaskaskia and Cahokia. During this time, these settlements were populated mostly by the French, who were not very fond of the British after the French and Indian War. Most were happy to join forces with George Clark to take on their common enemy. With the help of Father Pierre Gibault and Dr. Jean Baptiste Laffont, Clark soon gained support from the outpost at Vincennes as well. The only French settlements Clark could not sway were Detroit and a few other northern posts.

By late summer, British Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton had heard of Clark’s successes at Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes. His determination to reclaim these outposts caused him to leave Detroit with a mixed army of British soldiers, French volunteer militiamen, and Native American warriors. Clark’s second-in-command, Captain Leonard Helm, held Vincennes, known as Fort Sackville, at the time of Hamilton’s attack. Helm’s men were few in number and were quickly forced to turn over Fort Sackville to Hamilton’s army on December 17. The French settlers, who had previously supported Clark, quickly abandoned him when they saw the strength of Hamilton’s army.

It was often custom in 18th-century warfare for armies to send their soldiers home during the winter. British Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton followed this custom, which sealed the fate of Fort Sackville.

The British forces at Fort Sackville captured merchant and American sympathizer Francis Vigo when he didn’t realize the Americans no longer controlled Vincennes. Luckily, he was soon released and was able to provide valuable intelligence to Clark about the state of Fort Sackville – including their small numbers.

Armed with this new information, Clark decided to make the 18-day journey from Kaskaskia to Vincennes. He and his 170-man army trudged through the freezing weather of the Illinois countryside before arriving at Fort Sackville on February 23, 1779. French occupants who had previously helped Clark were happy to join him once again. They provided his army with food and dry gunpowder upon their arrival.

Clark and his forces soon began their assault on the British troops at Fort Sackville. The Americans surrounded the fort with many battle flags, giving Hamilton the impression they had far greater numbers than they did. They employed several more tactics that were designed to confuse, frighten, and disorient the British and force them to surrender.

On the morning of February 24, Clark sent a message to Hamilton demanding his surrender. Hamilton refused and Clark continued to fire on the fort for another two hours. Clark then demanded he surrender within 30 minutes or they would storm the fort. Hamilton again refused but proposed a three-day truce. They agreed to meet at a nearby church, where they worked out terms of surrender. The following morning, Hamilton surrendered the fort and his army laid down their weapons in front of the Americans.

After their victory, Clark’s army raised an American flag above Fort Sackville and fired 13 celebratory cannon shots. Clark renamed the fort for Virginia governor Patrick Henry, who had been the one to approve his plan of attack.

$1 Patrick Henry

Liberty Series

City: Joplin, MO

Printing Method: Rotary Press dry printing

Perforations: 11 x 10.5

Color: Purple

Patrick Henry Delivers Famous Speech

On March 23, 1775, Patrick Henry addressed the Second Virginia Convention to convince them to raise a militia.

Virginia native Patrick Henry was a prominent statesman best remembered for his fiery speeches that helped inspire the American Revolution. Henry was born in Hanover County, Virginia, and attended public schools for a short time. Although he was quite capable intellectually, it was generally understood that Henry lacked ambition at an early age. His father assumed responsibility for Henry’s education, and eventually set the young man up with a business that he soon bankrupted.

Henry received his license to practice law after just six weeks of study and quickly made a name for himself in a lawsuit known as the “Parson’s Cause.” The case concerned the question of whether the price of tobacco paid to clergy for their services should be set by the Colonial government or the Crown. In a brilliant oration, Henry cited a basic constitutional principle in English law, which held that only a representative assembly had the power to levy taxes on the people it represents. Because the colonists had no representation in the assembly, Henry argued, the King had no right to tax them. The first seeds of revolution were sown with Henry’s courtroom victory over the English crown.

In 1765, Henry was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses (the legislative body of the Virginia colony.) He soon became a leader and advocated the causes of less fortunate individuals against the old aristocracy. Henry also upheld the rights given to the colonies in their charters.

Henry proposed the Virginia Stamp Act Resolutions in 1765, which continued his argument against taxation without representation. He extended the argument to assert that the Colonial assemblies had the exclusive right to tax the colonies and could not assign those rights to the Crown. As accusations of treason rose from the assembly, Henry is said to have proclaimed, “If this be treason, make the most of it.”

Henry is best known for his March 23, 1775, speech to the Second Virginia Convention in Richmond. Days earlier Henry presented a number of resolutions supporting his idea that they needed to raise a militia. However, several present opposed his idea, believing they should be cautious and wait until the British crown replied to Congress’ most recent petition for peace.

The deeply divided house was close to deciding against committing troops when Henry rose to speak. He ended the profound speech with his most famous words, “I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!” The speech is credited with convincing Virginians to join the Revolutionary War.

Patrick Henry led a military force from Virginia during the Revolutionary War. Then, in 1776, he was elected to the first of five terms as Virginia’s governor. Two years later, Henry voted in opposition of the U.S. Constitution. However, he accepted its ultimate ratification and was instrumental in framing its first 10 amendments, which are known as the Bill of Rights. Henry died at his estate in Brookneal, Virginia, in 1799.

Click here to read the full text of Henry’s speech.

Governor of Virginia

Siege Of Vincennes

On February 24, 1779, George Rogers Clark led a siege of Vincennes, forcing the British to surrender.

After the French and Indian War, the British occupied the majority of the trans-Appalachian frontier. They soon passed the Proclamation of 1763, making the settlement of land west of the Appalachian Mountains illegal for colonists. The British responded harshly to settlers who ignored this decree, sending Native American war parties after trespassers.

In Kentucky, George Rogers Clark led a militia to defend the people against these attacks. However, Clark soon decided he would rather cut the attacks off at their British source. Clark developed a plan of action and brought it to Virginia governor Patrick Henry, who quickly approved it. By the summer of 1778, Clark and his army of militiamen were on their way down the Ohio River.

The men traveled over 120 miles before they reached and captured the British outposts at Kaskaskia and Cahokia. During this time, these settlements were populated mostly by the French, who were not very fond of the British after the French and Indian War. Most were happy to join forces with George Clark to take on their common enemy. With the help of Father Pierre Gibault and Dr. Jean Baptiste Laffont, Clark soon gained support from the outpost at Vincennes as well. The only French settlements Clark could not sway were Detroit and a few other northern posts.

By late summer, British Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton had heard of Clark’s successes at Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes. His determination to reclaim these outposts caused him to leave Detroit with a mixed army of British soldiers, French volunteer militiamen, and Native American warriors. Clark’s second-in-command, Captain Leonard Helm, held Vincennes, known as Fort Sackville, at the time of Hamilton’s attack. Helm’s men were few in number and were quickly forced to turn over Fort Sackville to Hamilton’s army on December 17. The French settlers, who had previously supported Clark, quickly abandoned him when they saw the strength of Hamilton’s army.

It was often custom in 18th-century warfare for armies to send their soldiers home during the winter. British Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton followed this custom, which sealed the fate of Fort Sackville.

The British forces at Fort Sackville captured merchant and American sympathizer Francis Vigo when he didn’t realize the Americans no longer controlled Vincennes. Luckily, he was soon released and was able to provide valuable intelligence to Clark about the state of Fort Sackville – including their small numbers.

Armed with this new information, Clark decided to make the 18-day journey from Kaskaskia to Vincennes. He and his 170-man army trudged through the freezing weather of the Illinois countryside before arriving at Fort Sackville on February 23, 1779. French occupants who had previously helped Clark were happy to join him once again. They provided his army with food and dry gunpowder upon their arrival.

Clark and his forces soon began their assault on the British troops at Fort Sackville. The Americans surrounded the fort with many battle flags, giving Hamilton the impression they had far greater numbers than they did. They employed several more tactics that were designed to confuse, frighten, and disorient the British and force them to surrender.

On the morning of February 24, Clark sent a message to Hamilton demanding his surrender. Hamilton refused and Clark continued to fire on the fort for another two hours. Clark then demanded he surrender within 30 minutes or they would storm the fort. Hamilton again refused but proposed a three-day truce. They agreed to meet at a nearby church, where they worked out terms of surrender. The following morning, Hamilton surrendered the fort and his army laid down their weapons in front of the Americans.

After their victory, Clark’s army raised an American flag above Fort Sackville and fired 13 celebratory cannon shots. Clark renamed the fort for Virginia governor Patrick Henry, who had been the one to approve his plan of attack.