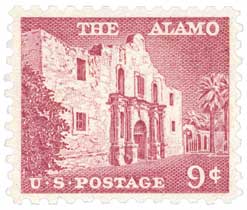

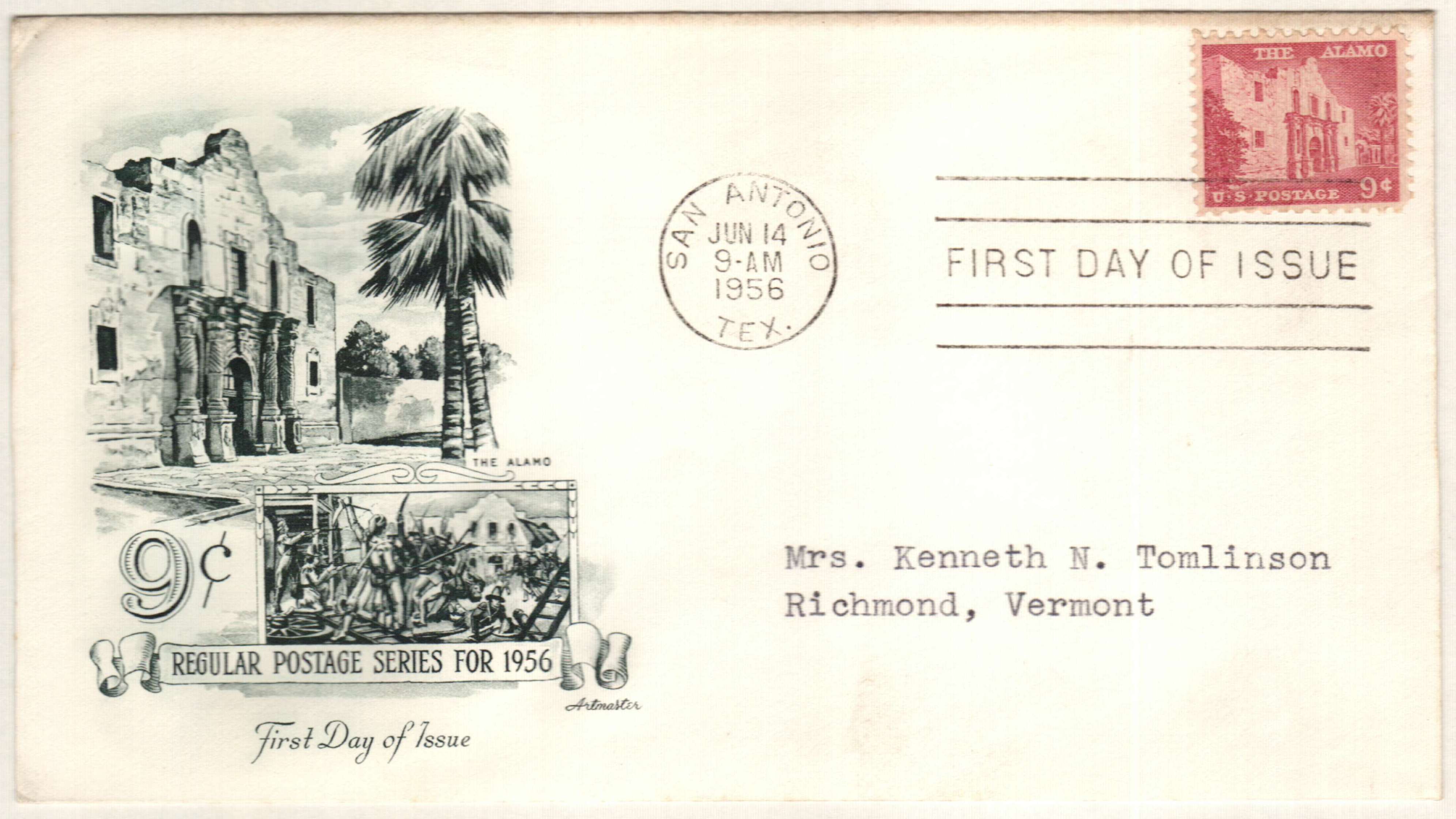

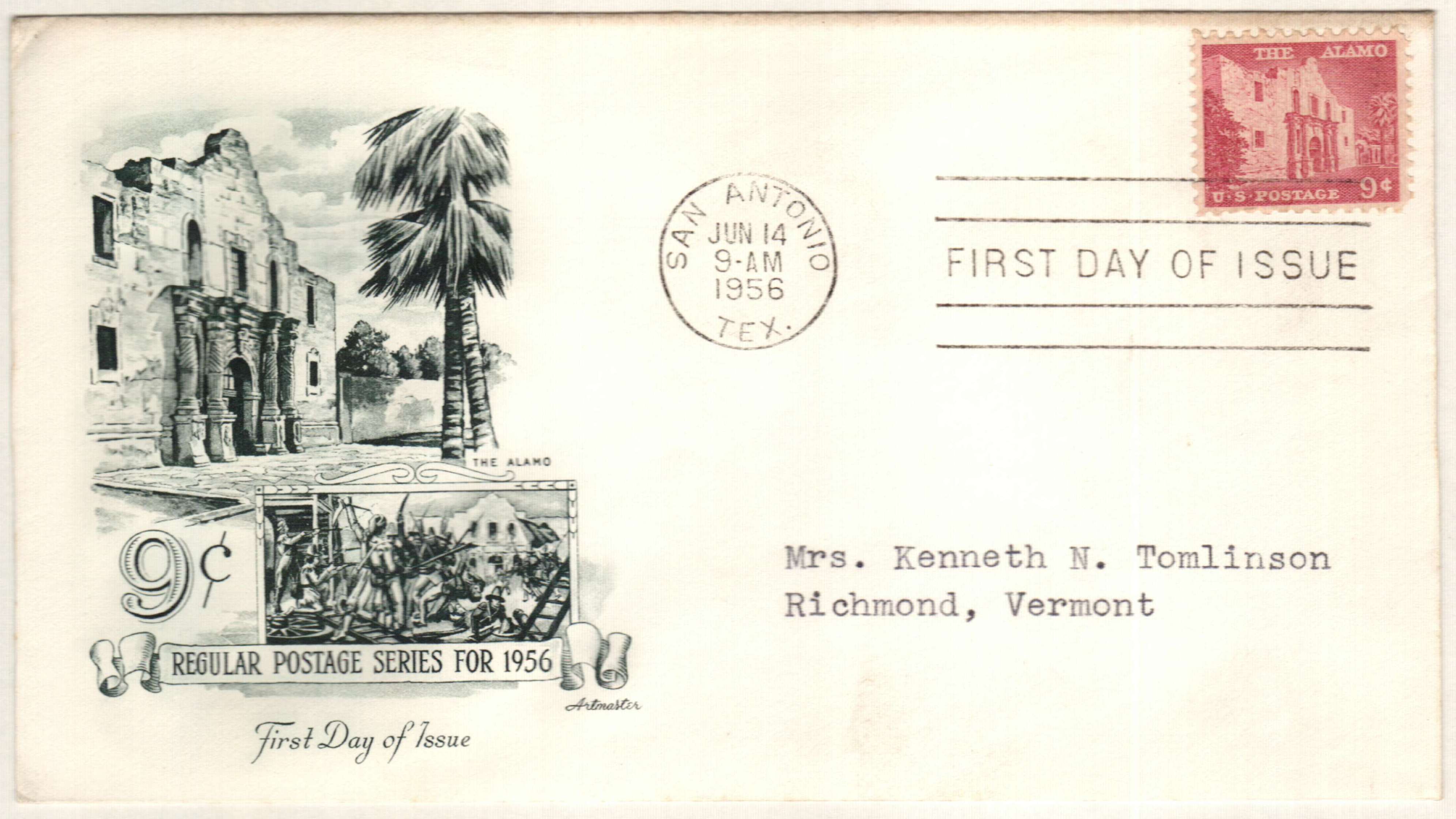

# 1043 FDC - 1956 Liberty Series - 9¢ The Alamo

9¢ The Alamo

Liberty Series

City: San Antonio, TX

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforations: 10½ x 11

Color: Rose lilac

Remember The Alamo!

Around 1718, the Spanish built a mission, San Antonio de Valero, in San Antonio. The mission, which consisted of a monastery and church surrounded by a high wall, later came to be known as “the Alamo,” after the Spanish word for the cottonwood trees that surrounded it. The people of Texas occasionally used the mission as a fort.

In 1820, a Missouri banker, Moses Austin, obtained permission from Spanish officials to establish an American colony in Texas. Soon, more Americans received land grants from Mexico. Between 1821 and 1836, the number of settlers in the area grew to about 30,000 – and most were Americans. The Mexican government became concerned over the high number of Americans in its territory, and in 1830, Mexico halted American immigration. Relations between the settlers and the government quickly deteriorated. In 1834, General Antonio López de Santa Anna, a Mexican politician and soldier, overthrew the Mexican government and established himself as a dictator.

After a few clashes between Texans and Mexican soldiers, Texas leaders organized a temporary government on November 3, 1835. Texas troops captured San Antonio on December 11, 1835. Enraged, Santa Anna sent a large army to San Antonio to put an end to the uprising.

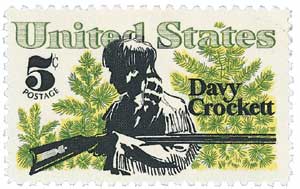

On February 23, 1836, about 5,000 of Santa Anna’s troops approached San Antonio. The Texans were caught by surprise. About 150 Texans took refuge in the Alamo, preparing for battle. While Santa Anna laid siege to the fort, only a small number of reinforcements were able to reach the Alamo, raising the number of defenders to 187. The defense included several frontier heroes, including James Bowie and Davy Crockett.

The Texans bravely protected the fort. Eventually, they ran low on ammunition and were unable to return fire. Then on March 6, 1836, Santa Anna’s troops were able to scale the walls of the Alamo. The Texans fought using their rifles as clubs, though the only survivors were the wife of an officer, Mrs. Dickenson; her baby; her nurse; and a young black boy.

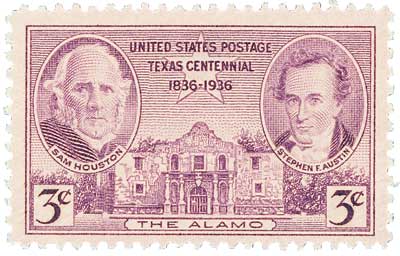

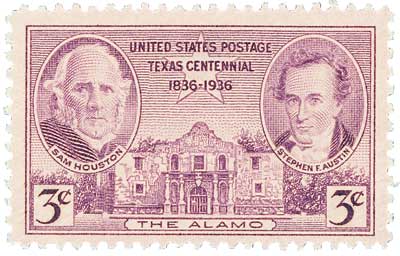

“Remember the Alamo” became the battle cry of the Texas independence struggle. The defense of the Alamo had bought the Texans valuable time to organize their remaining forces. On April 21, Sam Houston led a smaller Texan army against Santa Anna’s forces in a surprise attack at the Battle of San Jacinto. The Texans were able to capture Santa Anna himself and forced him to sign a treaty giving Texas its independence.

Texas remained an independent republic for ten years. Then on December 29, 1845, it was admitted to the Union as the 28th state.

9¢ The Alamo

Liberty Series

City: San Antonio, TX

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforations: 10½ x 11

Color: Rose lilac

Remember The Alamo!

Around 1718, the Spanish built a mission, San Antonio de Valero, in San Antonio. The mission, which consisted of a monastery and church surrounded by a high wall, later came to be known as “the Alamo,” after the Spanish word for the cottonwood trees that surrounded it. The people of Texas occasionally used the mission as a fort.

In 1820, a Missouri banker, Moses Austin, obtained permission from Spanish officials to establish an American colony in Texas. Soon, more Americans received land grants from Mexico. Between 1821 and 1836, the number of settlers in the area grew to about 30,000 – and most were Americans. The Mexican government became concerned over the high number of Americans in its territory, and in 1830, Mexico halted American immigration. Relations between the settlers and the government quickly deteriorated. In 1834, General Antonio López de Santa Anna, a Mexican politician and soldier, overthrew the Mexican government and established himself as a dictator.

After a few clashes between Texans and Mexican soldiers, Texas leaders organized a temporary government on November 3, 1835. Texas troops captured San Antonio on December 11, 1835. Enraged, Santa Anna sent a large army to San Antonio to put an end to the uprising.

On February 23, 1836, about 5,000 of Santa Anna’s troops approached San Antonio. The Texans were caught by surprise. About 150 Texans took refuge in the Alamo, preparing for battle. While Santa Anna laid siege to the fort, only a small number of reinforcements were able to reach the Alamo, raising the number of defenders to 187. The defense included several frontier heroes, including James Bowie and Davy Crockett.

The Texans bravely protected the fort. Eventually, they ran low on ammunition and were unable to return fire. Then on March 6, 1836, Santa Anna’s troops were able to scale the walls of the Alamo. The Texans fought using their rifles as clubs, though the only survivors were the wife of an officer, Mrs. Dickenson; her baby; her nurse; and a young black boy.

“Remember the Alamo” became the battle cry of the Texas independence struggle. The defense of the Alamo had bought the Texans valuable time to organize their remaining forces. On April 21, Sam Houston led a smaller Texan army against Santa Anna’s forces in a surprise attack at the Battle of San Jacinto. The Texans were able to capture Santa Anna himself and forced him to sign a treaty giving Texas its independence.

Texas remained an independent republic for ten years. Then on December 29, 1845, it was admitted to the Union as the 28th state.